Tune in tomorrow to read about the recording destined to sweep the classical Grammys!

Archive for the ‘Why I Left Muncie’ Category

A Sure Grammy Bet

Wednesday, October 3rd, 2012Polisi for President

Wednesday, September 26th, 2012by Sedgwick Clark

Of Lincoln Center, that is.

The announcement on Tuesday (9/25) that Reynold Levy, 67, president of Lincoln Center since 2002, considers his work done and will move on at the end of next year, was a surprise. I figured there would be more total remakes like Alice Tully Hall. Under Levy, all the $1.2 billion renovations of the past seven years were accomplished on time and on budget. (Lincoln Center’s detailed press release offers the full official information.) Not in the release is my own observation that the populist move begun by his predecessor Nat Leventhal has bloomed full flower, with summer events never envisioned by John D. Rockefeller and LC’s founding fathers.

I never quite believed my friend Betsy Vorce, v.p. of public relations at LC, who has been saying for some time that the renovations are nearly finished. I’ll certainly be happy to see the scaffolding removed. But what about Avery Fisher Hall, which I attend more than any other venue at LC? Won’t LC be in charge of the inevitable work there, or will the NYPhil be responsible? We all know that renovation – mainly acoustical – is desirable. I speak, of course, as an audience member, not as one aware of day-to-day operating necessities such as dilapidating plumbing, etc. (This is not the time to revisit this difficult subject. I’ll just say that I’ve heard the NYPhil sound magnificent in Fisher under Masur, Maazel, Gilbert, and Davis, and unlistenable under Mehta.)

Tomorrow (9/27), in honor of Levy’s achievements, an 83-foot pedestrian bridge on the Walter Reade Theater level connecting the Rose Building to the main Lincoln Center “campus” will be opened and dedicated The President’s Bridge by Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and other dignitaries.

Back, however, to the subject of my title: Joseph Polisi. He has been president of The Juilliard School for 28 years and was honored by Musical America as Educator of the Year in 2005. His reputation as a master diplomat — a necessary quality when dealing with LC’s 11 turf-sensitive constituents – is impeccable and widespread. He had responsibility for the many alterations in the Juilliard building, most notably changing the school’s entrance from the original “back-door” location of 66th Street onto the more significant 65th Street where the action is. As author of American Muse: The Life and Times of William Schuman (Amadeus, 2008), he undoubtedly knows the ins and outs of everyone and everything to do with Lincoln Center, for Schuman was LC’s first president. Seems to me that Polisi would be ideal.

Looking Forward

My week’s scheduled concerts:

9/26 at 7:30 David H. Koch Theater. New York City Ballet. Stravinsky-Blanchine: Violin Concerto; Monumentum pro Gesualdo/Movements for Piano and Orchestra; Duo Concertant; Symphony in Three Movements.

9/27 Paul Hall (Juilliard School). Joel Sachs, piano; Cheryl Seltzer, piano; vocalists. Music of Henry Cowell.

10/3 at 7:00 Carnegie Hall. Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus/Riccardo Muti. Orff: Carmina burana. OPENING NIGHT.

Stravinsky Lovers Unite!

Wednesday, September 19th, 2012by Sedgwick Clark

Alastair Macaulay’s review in Thursday’s Times reminded me of the two-week Stravinsky-Balanchine mini-festival that opens New York City Ballet’s fall season. No performing organization in the world offers so much Stravinsky in a single season—and so authoritatively. These two weeks commemorate NYCB’s 1972 and 1982 Stravinsky festivals; I saw every program of both those festivals. There are only three programs this time around, and every music and ballet fan should see them. I’ll have more to say when I have.

The Dying Artform on TV

I resist hitting the mute button when I hear classical “beds” for TV commercials. Within five minutes last week, a movement from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons served as background to Donald Sutherland’s Delta commercial, followed by another baroque beauty in the next round of commercials. A couple of hours later on Nightline, the ominous pulsating of waves lapping onto the beach of Rachmaninoff’s Isle of the Dead underscored a commercial for The Master, a new movie starring Philip Seymour Hoffman. I’m definitely interested in hearing how the music is used, and reviews were positive, so if it’s still in the theaters when my MA Directory deadline is over I won’t wait for the video.

Huh?

The Republicans scorn fact checking, but the Mannes School shouldn’t. Descriptions of two Mannes orchestra concerts in a press release sent my mind reeling. In an effort to be kind, I won’t divulge the young author’s name and assume that he likes the music.

On Friday, September 28 at 7:30 p.m., the orchestra will perform Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin, an act from the early 20th century pantomime ballet Trauer-Symphonie by Haydn, and Bernard Herrmann’s North by Northwest Suite.

On Tuesday, October 30 at 7:30 p.m., the program will include work from The Firebird by Stravinsky and Ravel’s Daphnis et Cholé Suite No. 2.

In the first concert, the students will almost certainly play Bartók’s 20-minute Suite from The Miraculous Mandarin, not the complete version with chorus. Let’s further assume that a comma is missing after “ballet” and that Haydn did not arrange Bartók’s music into separate acts and retitle the work Trauer-Symphonie. Still, what does “an act from the early 20th century pantomime ballet” mean? Bartók’s continuous half-hour ballet has no “acts,” although there are three “decoy games” where three tramps force a girl to seduce men from the street into an apartment to rob them. The suite contains all three of the decoy games.

I haven’t heard of an official North by Northwest Suite. If I were in town, I’d probably go to this concert just to hear how much of this great Herrmann film score would be played. But I’ve got all the recordings and a laserdisc and two DVDs of the film. (I see that a Blu-ray version has just been released too.)

As for the second concert, what in heaven’s name does “work from The Firebird” specify? The complete 45-minute ballet music? One of Stravinsky’s suites (1910, 1919, or 1945)? And the unfortunate typo in Ravel’s ballet suite makes poor Chloé sound like an intestinal bacterium.

Looking Forward

My week’s scheduled concerts:

9/19 Avery Fisher Hall. New York Philharmonic/Alan Gilbert; Leif Ove Andsnes, piano. Kurtág: …quasi una fantasia … . Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 3. Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring. OPENING NIGHT.

9/20 Miller Theater. ICE/Steven Schick; Jessica Aszodi, mezzo. Cage: Music for ___; Variations III; Atlas Eclipticalis; Radio Music; 1’5½” for a string player; Amores; The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs. Boulez: Le marteau sans maître.

9/24 Alice Tully Hall. Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Mozart: Serenade in C minor for Winds, K. 388. Kodály: Serenade for Two Violins and Viola, Op. 12. R. Strauss: Serenade in E-flat for Winds, Op. 7. Dvořák: Serenade in D minor for Winds, Cello, and Double Bass, Op. 44. OPENING NIGHT.

Kudos for a Critic?

Wednesday, September 12th, 2012by Sedgwick Clark

Frankly it was astonishing: A disingenuous “culture” editor of “all the news that’s fit to print” shunts a classical-music critic from his 35-year beat into a position called “general culture reporter,” and within a day 500 angry readers sign a petition to reinstate him. Two days later the number had grown to 1,100! By noon today (9/12), the number had risen to 1,357. And remember, we’re talking about a critic of the high art that is supposedly dying faster than the printed newspaper.

My phone calls and e-mails haven’t let up since I blogged on the subject last week.

Gil Shaham’s 20th-century Concertos

Just to show that I’m not squeaky clean either, I’m about to quote from a press release! It’s about the upcoming season of Musical America’s 2012 Instrumentalist of the Year, Gil Shaham, who has been engaged in “one of the most imaginative programming concepts in years,” to quote our own words.

Now entering its fourth season, Shaham’s long-term exploration of iconic “Violin Concertos of the 1930s” was conceived when he realized how many outstanding 20th-century violin concertos derived from that fateful decade. The coming year brings the project’s first recording, on which he joins forces once again with David Robertson, his brother-in-law and frequent musical partner. Due for release on the violinist’s own Canary Classics label, the new album features three of the decade’s most evocative concertos, performed with the world-class orchestras of three nations, all with Robertson on the podium: Stravinsky’s (1931) with the BBC Symphony Orchestra; Berg’s (1935) with the Dresden Staatskapelle; and Barber’s (1939) with the New York Philharmonic, with whom Shaham previously collaborated to impress the New York Times with their “rich-toned, gracefully shaped performance.”

In the concert hall, Shaham performs no fewer than seven violin concertos of the 1930s over the coming season. Barber’s is the vehicle for his return to the New York Philharmonic, now with music director Alan Gilbert (Nov 29 – Dec 1), and for appearances with Marin Alsop and the Baltimore Symphony (Sep 20–22). He reprises the Stravinsky with both the San Francisco Symphony led by Michael Tilson Thomas (June 18–20) and the Orchestre de Paris under Nicola Luisotti (Jan 9–10), and plays the Berg with Michael Stern directing the Kansas City Symphony (May 31 – June 2). Other 1930s masterpieces showcased over the coming season are William Walton’s concerto (1938-39), which headlines the violinist’s appearances with the Chicago Symphony and Charles Dutoit (Nov 8–11); Benjamin Britten’s (1938-39), which he undertakes with both the Boston Symphony conducted by Juanjo Mena (Nov 1–6) and the Montreal Symphony under James Conlon (Sep 26); Bartók’s Second (1937–38) with the Orchestre de Paris led by Paavo Järvi (March 20–21); and Prokofiev’s Second (1935) on Japanese tour with the NHK Symphony (March 7–11).

I combed with fingers crossed through those two paragraphs for the name “Hindemith,” who wrote what I consider the most underrated Violin Concerto of the 20th century. When Gil received his Musical America award I goaded him into promising that he would add the concerto to his repertoire, and I hope that I’ll see it on a New York Philharmonic schedule soon.

While awaiting the Shaham rendering of this supremely melodic masterpiece, those who wish to test my opinion may listen to Isaac Stern’s Columbia recording with Bernstein and the NYPhil now on Sony Classical. I had the pleasure of sitting next to Stern at a Carnegie Hall season announcement lunch a decade or so ago and told him of my regard for this piece because of his recording and that it was my favorite violin concerto of that century. He replied that, much as he loved the Hindemith, he would personally choose the Bartók Second and Berg concertos as his favorites.

Ah, the memories of Stagedoor Sedgie.

Allan Kozinn: The Times Eats Its Own

Wednesday, September 5th, 2012by Sedgwick Clark

The word spread like wildfire: Allan Kozinn, a classical-music reviewer at the New York Times for 35 years and a staffer since 1991 had been transferred from the reviewing staff to general cultural reporting. His last review ran on Monday, September 3, Labor Day – the same day that Norman Lebrecht broke the story (see link below), alleging that the change in Kozinn’s status was the result of Culture Editor Jon Landman’s poisonous office politics and a knife in the back delivered by longtime Classical Music Editor James R. Oestreich, his friend of three decades, who feared for his own job. (For the record, I know all of the dramatis personae except for Lebrecht and Landman, and have edited articles by all of the writers mentioned below except for Tommasini, Wakin, and Eichler.)

Classical-music fans are enormously loyal, but even so, the response to Kozinn’s sacking as a reviewer was astonishing, with musicians, writers, and readers in often vituperative discussion. Readers responding to Lebrecht’s blog wrote of Kozinn’s “lack of personal bias and agenda” and “trustworthy standard of intelligence, erudition, sensitivity, and judiciousness.” They called him “a truly eloquent lover of music” and “a tremendous loss for the Times [and for] the music world.” There was even a “Save Kozinn” petition that had over 500 signatures by midday Tuesday!

To me personally, the overriding merit of Kozinn’s reviews has always been his exceptional ability to describe what the music and performance sounded like, which is no easy task. I can’t get to every concert I wish, and I’ve counted on Kozinn to elucidate the baroque and contemporary repertory he had staked out at the Times. Kozinn covered more concerts than any of his colleagues, some 250 per year. He has always been there for his editors. (When John Cage died suddenly, Kozinn wrote a 3,000-word obit in four hours!) If I believed that the executive editors still give a damn about classical music in this time of newspaper death throes and the worldwide embrace of popular culture, I would suggest that they will regret this move.

Here’s the inter-office skinny: When staffer Bernard Holland (whose elegant pen is greatly missed) retired in 2005, his position was not filled, leaving only three full-time staffers (Anthony Tommasini, Oestreich, and Kozinn) and three stringers (currently Steve Smith, Vivien Schweitzer, and Zachary Woolfe) who are limited to three reviews a week and occasional features. Landman (who I had never even heard of before Labor Day) and Oestreich (whose grumpy reviews share Kozinn’s clarity) are dying to get Woolfe on staff – understandably so, as he is highly readable and controversial, especially in opera (whose aficionados detest him). But apparently the only way to finagle that was to banish Kozinn from a classical beat altogether because Dan Wakin does a superb job covering classical news. The Times has an abysmal record of late in keeping its best classical stringers: When the paper refused to put them on staff, Alex Ross left for The New Yorker, Anne Midgette for the Washington Post, and Jeremy Eichler for the Boston Globe.

Evidently, Landman and Oestreich have no wish to repeat such blunders. But Landman has already proven himself to be an ignorant judge of the Times’s classical readership. It may be small, but it’s loyal and buys newspapers – or whatever technological form the news comes in for the time being. The good grey lady as cannibal is a sad image for this Times reader of five decades to countenance.

Lebrecht blog:

http://www.artsjournal.com/slippeddisc/2012/09/exclusive-new-york-times-demotes-a-critic.html

Vivat Boulez

Wednesday, August 29th, 2012by Sedgwick Clark

It’s not often that one can gratefully quote British musical mudslinger (or “gadfly,” depending upon your point of view) Norman Lebrecht. But his report on Sunday (8/26, Arts Journal) that Pierre Boulez had begun rehearsals in Lucerne months after “an eye operation that went wrong” was the best news I’ve heard all year. Boulez had cancelled concerts in Chicago and Cleveland last season due to failing eyesight, and fear among friends and followers was that he would never conduct again because of his invariable use of a score. (He told me in an interview that he never fails to learn new insights from the score during performance.) Lebrecht publishes a photo of the French maestro congratulating Franz Welser-Möst after a Cleveland Orchestra concert in Lucerne on Sunday, commenting that “he looked tanned, relaxed, happy, and far younger than his 87 years.” Vivat!

A Reader Responds

I often wonder, especially when faced by a deadline, who reads this stuff? Snail mail resoundingly replied on Tuesday (8/28) with a new CD from ECM’s Tina Pelikan, who had read my favorable review last week of Louis Langrée’s Mostly Mozart performances of Lutosławski’s Musique funèbre and Bartók’s Third Piano Concerto. She kindly sent me Dennis Russell Davies’s Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra recordings of the Lutosławski work and Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances, Divertimento, and Seven Songs, featuring the Hungarian Radio Children’s Choir in the songs (ECM 2169). Davies’s softer textures contrast markedly with Langrée’s slashing attacks; in fact, with the Frenchman’s interpretation so vividly in mind, I barely recognized Luti’s Funeral Music. There being no such thing as a “definitive” performance, I’m happy to have heard both.

Mostly Mozart’s Genial Firebrand

Wednesday, August 22nd, 2012by Sedgwick Clark

I ran into Mostly Mozart’s music director, Louis Langrée, prior to Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s concert that I reviewed last week, and told him how much I was looking forward to hearing the Lutosławski and Bartók works he was conducting a week later. His eyes widened and he smiled broadly, saying how much he loved their music. New Yorkers are used to this genial maestro’s elegant performances of baroque and classical repertoire, but now I suspect that Langrée’s restrictive MM connection has caused us to lose out on a more well-rounded musician than we realized.

The conductor’s demonic fervor in Lutosławski’s Bartók-flavored Musique funèbre (1958) was palpable. No less so was the surprisingly rich tone that he drew from the MM Festival Orchestra strings – no non-vibrato nonsense here! Equally stirring was Bartók’s Piano Concerto No. 3 (1945), with Jean-Efflam Bavouzet in the solo seat. The Third was once thought inferior to the composer’s more aggressive First and Second; program annotator Paul Schiavo’s descriptive weasel words are “user-friendly,” placed in quotes so we won’t accuse him personally of condescension. True, Bartók was dying of leukemia and tailored the concerto for his wife to play when he was gone. But its standing in the composer’s oeuvre is no less distinguished than the first two: It’s just different.

György Kroó, in his insightful A Guide to Bartók, refers to the “free, airy atmosphere of morning” in the concerto and “the chattering chirping birds, meadows and fields seen in the bright spring sunlight” – a change from the characteristically Bartókian “night music” slow movements of many earlier works. Kroó draws an analogy “to the work of the greatest of geniuses, the graceful lightness of the work composed by Mozart on his death-bed.” Continuing his Mozart analogy, he compares the finales of both Mozart’s and Bartók’s final piano concertos: “Both works seem to dance and soar in a strange state of euphoria towards eternity. . . .”

The Bartók certainly did under Bavouzet and Langrée, zipping along joyously with breathless delight – certainly more vivace than the last two performances I’ve heard in concert, by the mummified Radu Lupu and anemic András Schiff, and equaling my favorite recording, by Julius Katchen and István Kertész. Only the cackling woodwinds seemed underplayed. The composer did not live to orchestrate the last 17 bars of the Third, leaving the task to his student, Tibor Serly. Perhaps for this reason, Langrée felt free to add a bass drum to the final chord, à la Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G. Very effective.

Following intermission, the maestro turned in an impeccable Mozart 39th. Makes me look forward to the coming season.

Yannick, the (Almost) Philadelphian

Wednesday, August 15th, 2012by Sedgwick Clark

At Mostly Mozart on August 3, Yannick Nézet-Séguin’s largely direct, unfussy, and vigorous music-making was quite satisfying both on its own and as an augury of his future leadership of the embattled Philadelphia Orchestra. I’ve heard that curious Philly audiences have flocked to his appearances since he became music director-designate, and it was clear that this MM audience was energized by his leadership of Beethoven’s Second Symphony and Haydn’s “Nelson” Mass (a.k.a. “Mass in Time of War”). I had only heard him conduct previously twice, at the Met, in a Carmen whose frenzied Prelude alienated me instantly and a thankfully more judiciously paced Faust. But I wanted to hear him in concert, where I feel more at home.

Apart from the Mostly Mozart Orchestra’s whiny, vibrato-less string playing and slight relaxation for the Scherzo’s trio, I found the Beethoven exemplary, with the timpanist’s use of hard sticks impelling the music dynamically forward. The Haydn Mass, too, benefitted from fleet tempos and fine playing and singing. Yannick (pronounced “Yan-NEEK”), as I’m told he likes to be called, conveniently avoiding American mangling of his hyphenated French-Canadian surname, seems to thrive in vocal works, and for his first New York appearance with the Philadelphians, at Carnegie on October 23, he will lead Verdi’s Requiem.

While I suspend further judgment until we’re served with more rearguard Romantic rep—the orchestra’s beloved Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Rachmaninoff, etc.—this choice is infinitely more appropriate for this orchestra than the wayward Christoph Eschenbach. But one fact is undoubted: This great orchestra, which has just emerged from bankruptcy, stands at the top of its form thanks to its inherent esprit de corps and its interim leader of four years, Charles Dutoit. He knew how to get the best from these superb musicians, and in another month the ball will be in Yannick’s court.

AfricaViews, Part 2

Wednesday, August 8th, 2012

By popular demand, I offer another baker’s dozen of Africa photos to tide over a humid summer. Our last two weeks of May were in South Africa’s fall season—very dry, with Kruger National Park’s brown grass sparsely green only near the river. The jungle foliage may have desiccated, but the bare bush gave us a better view of animals that, even then, blended into the background to an uncanny degree. In the morning the temps were around 40° Fahrenheit, and we dressed in five layers and bundled under blankets as the Land Rover whisked us to the bush to observe the changing of the wildlife guard. By 9 a.m. several layers had been shed, and at midday it was nearly 80°. Our late-afternoon return to the bush required that we dress in retrograde. The unexpected benefit of the season was that bugs were near nonexistent. Usually a magnet for their stingers, I didn’t get a single bite.

Photos: Sedge and Peggy Kane.

Once again, thanks to Stephanie Challener for her assistance in posting these photos.

Sunrise. The terrain is dotted with dead trees, stark and dramatic in the African sky. Peggy and our intrepid travel companions, Peter Clark and Jonathan Rosenbloom, would sigh in feigned frustration at my continued requests to stop the truck for a photo, but even Peter began snapping them after a while.

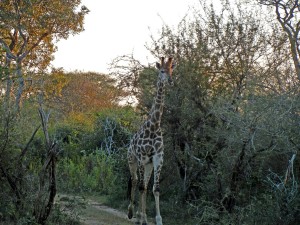

Our first day on safari began uneventfully. And then, as we turned a corner, there was a giraffe staring at us interlopers. We stopped. He stared. And when we stayed still he lumbered past us impatiently.

Look at those teeth! I was perfectly happy to let the camera do the close-up for this shot of a baboon demanding space for his family.

Talk about self confidence. This momma leopard allowed us to invade her territory without a flicker of concern. Of course she was well acquainted with the Land Rover and the respect of its inhabitants, but a foolish visitor might still be tempted to interpret her relaxed aplomb as an invitation. Not a good idea!

Mother elephant and child lunching in the bush. We were close up in this photo, but in many we took from afar we could barely distinguish the animals from their surroundings.

Tracking a leopard at night. We were on our way back to Lion Sands when, like a flash, a bush buck dashed across the road from the left, pursued immediately by a young leopard. We could hear a skirmish, but the buck got away and the leopard returned to the road, where our tracker pinpointed the cat in the spotlight. Our ever-competitive driver, Kyle, followed him into the bush, and we bumped and jostled in pursuit around the pitch black environs for nearly half an hour before returning to the camp.

Don’t tread on me. One of the Big 5 (a category of mammals most desired by hunters, including the lion, leopard, elephant, and rhino), the African buffalo is a very aggressive and dangerous animal, not to be messed with.

Not one of the Big 5 is the hippopotamus, perhaps due to its ungainly weight. This smiling hippo appears far happier in the cool water than did his grumpy, out-of-water sibling in last week’s photos.

Only photos from the air could possibly capture the awesome immensity of Victoria Falls’ Seven Wonders of the World status. My photos were too close: It looked like merely another water fall. But Peter took a shot from the back yard of the Victoria Falls Hotel, where we stayed, and the cloud-like mist billowing in the distance suggests the falls’ wide-range power. Photo: Peter Clark.

It used to be thought that African elephants could not be trained. In fact, reported Robert Osborne last week when TCM showed all the Weissmuller-O’Sullivan Tarzan films in one day, MGM used the more docile Indian elephants, which have smaller ears, and attached fake, large ears to them! But the Elephant Back Safari program gives the lie to that old canard, for here’s Coco, with genuine ears flared, as Sedge and Peggy make friends with her before riding her. If you care to see us in Coco’s saddle, check out the photo in my May 30 blog, “Bwana Clark.”

A Procrastinator’s African Photo Log

Wednesday, August 1st, 2012by Sedgwick Clark

I’ve been promising to run photos from our African vacation in this space almost since we returned two months ago. The lone dissenter (“You’re not really going to post photos from your Safari on Musical America.com!! Oy.”) was far outvoted. Only yesterday I ran into a friend who had seen photos posted in a decidedly more timely fashion on our fellow traveler Peter Clark’s Facebook page, and she expressed interest in seeing more. It was difficult to choose from all we took, and I may even have more next week.

The trip was planned by ROAR AFRICA, which we all agreed thoroughly lived up to advance praise. We flew to Johannesburg but after a four-hour layover continued to Cape Town rather than face the former’s notorious crime level. Both of the cities’ airports were strikingly up-to-date and clean, however. Once in Cape Town, we were met by ROAR AFRICA guide Andy Ward, a retired geography teacher, who had the answers for all of our questions and made us feel completely safe and at ease.

Exploring the wine lands and partaking in wine, goat cheese, and chocolate (!) tastings was a relaxed way to overcome 20-some hours of travel. We also visited the Spier Wine Estate, which houses a bird sanctuary and a Cheetah Outreach Program where over 20 of these beautiful, endangered cats live.

We also visited the Hout Bay Music Project, which I wrote about on May 24, while still in Africa. We took so many photos that I’ll put a few of them together in a future week of their own.

The first three photos cover our time in Cape Town before flying east to Kruger National Park, where more colorful beasts roam. All photos were taken by yours truly or Peggy Kane unless otherwise noted.

Many thanks to Stephanie Challener for her assistance in posting these photos.

(left to right) The intrepid travelers: Peter Clark, Sedge, Peggy Kane, and Jonathan Rosenbloom at the Cape of Good Hope.

Nelson Mandela’s prison cell for 18 years on Robben Island. The Dutch settled the Cape in the mid-1600s and established the island primarily as a prison. Since 1997 it has been a living museum and a focal point of South African heritage, with tours given by former prison inmates.

Sedge and Peggy on 3,000-foot Table Mountain with Cape Town in background to the west. Possessed of an unfortunate urge to jump from such heights, I dared venture no further out onto this overlook’s precipice, to Peggy’s amusement. Many young visitors would lean over the railing, presumably to enjoy the precipitous drop, but compelling me to head for center ground. On our 3,500-foot descent in the cable car, to avoid the 360-degree views afforded by the car’s revolving floor, I kept my cookies down by engaging our guide Andy in an eyes’-locked discussion about the upcoming American presidential election.

Safari at dawn with tree and crescent moon. Bush safaris in the Tinga and Lion Sands Game Preserves were from 6-9:00 a.m. and 4-7:00 p.m., returning to camp for breakfast and for dinner, respectively. In between, we could watch the elephants cavort in the Sabie River or take a nap.

It’s a matter of pride for the safari rangers and trackers to find the Big 5 (lion, leopard, elephant, rhino, and buffalo), as well as hippo and giraffe. A tip from a fellow ranger led us to this scene. The giraffe had been killed by different lions three days before, and these lions (pictured) had ventured out of their own territory from a neighboring park across the Sabie. Before we approached the kill, our ranger stopped the Land Rover and plucked fever bush leaves for each of us to smell. We were very grateful.

A hippo close-up on a walking tour. Unlike when we were safely seated in the Land Rover, our ranger and tracker each carried a rifle. We were warned that if he should turn on us and charge, the worst thing we could do would be to run! Fortunately he lumbered off into the river.

Of the Big 5, elephants are the most prolific. We have photos of them everywhere, crossing highways, jamming traffic as they lumber down dirt safari roads, knocking down trees to eat their roots, crossing the Sabie River.

A crocodile lies in wait beneath weaver bird nests, while two terrapins clamber out of the water and a white heron keeps watch.

Despite reassurance that this family of grazing rhinos was allowing us into its territory, being just 20 feet from this most prehistoric-looking of living animals generated a palpable sense of awe and danger.