By Rachel Straus

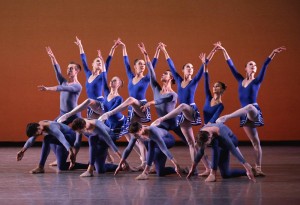

Justin Peck’s “Year of the Rabbit” begins with a whirligig virtuoso solo by Ashley Bouder. The principal New York City Ballet dancer performs her multiple turns into off-kilter leaps with playful abandon. The total effect is that of “Road Runner” cartoon: Here comes Bouder. Beep Beep! The company that George Balanchine developed is known for moving speedily. But Justin Peck, a 25-year-old corps dancer who has now made three works for NYCB (this is his second), gets his dancers to move even faster than the company’s founding choreographer. About half way through Peck’s 2012 piece—to Michael P. Atkinson’s orchestration of Sufjan Stevens’ electronica album “Enjoy Your Rabbit” (2001)—one had to wonder what all the hurry was about.

Peck is the first choreographer who Ballet Master in Chief Peter Martins has supported that grew up firmly in the Internet age. While Christopher Wheeldon (age 39) and Alexei Ratmansky (age 44) surely have the latest gadgets, and Martins’ support, it is Peck’s fastidiously fast choreography that evokes the furrowed brow of our new century.

Back in the 1980s, it was Twyla Tharp who upped the ante on choreographic tempi. She taught aerobics as part of her company’s training. With “In the Upper Room” (1986), she featured dancers in tennis shoes and tracksuits, jogging up and down as though they were on a Stairmaster to heaven. But while Tharp’s “Upper Room” evokes the timelessness of Zen, via repetition of speedily performed choreographic leitmotifs, Peck’s interest in speed feels like young man’s game–with a smidgeon of ADD.

Though speed feels like the subject of “Year of the Rabbit,” it also concerns contemporary ballet and its values. In the center of the work, there is a romantic pas deux for the wonderfully expressive dancers Teresa Reichlen and Robert Fairchild. The pair appears to be questing for each other’s love: they dance in separate fiefdoms of the stage, created by boundaries formed out of dancers from the opposite sex. Yet as soon as Fairchild and Reichlen touch, they go their separate ways. The pas de deux’s erotic potency lies with the pair’s physical separation. Actual intimacy isn’t the point, just as Facebook concerns looking and commenting at friends and loved ones from the safety of one’s digital screen.

Peck’s musicality, in which he corresponds, sidles, and departs from Atkinson’s melodic lines, demonstrates that he is astute. His choreography for the corps is also notable. He continuously weaves the corps through six soloists’ dancing, thus blurring (and democratizing) the typical separation between leading and supporting dancers. All of this movement takes place place swiftly and efficiently, making “Rabbit” an indicator of our times.

Fall for Dance Festival: Recapping Program 1, 2 and 5

Wednesday, October 17th, 2012By Rachel Straus

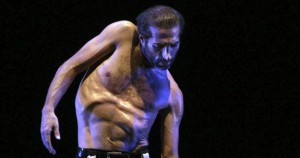

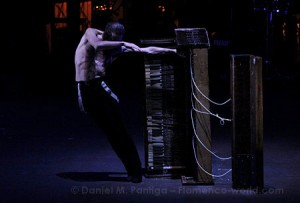

The seventh annual Fall For Dance Festival came to a meaty close on October 13. Program five at New York’s City Center trafficked in high testosterone, thanks to China’s LPD-Laboratory Dance Project’s No Comment (2002) and Yaron Lifschitz’s Circa (2009), which is also the name of the Australian acrobatic troupe. In both works the body was treated like a battering ram.

Circa by Justin Nicholas Atmosphere Photography

In Circa, the performers used not only their fellow artists’ thighs and shoulders, but also their faces, as launching pads for balancing in midair and jettisoning across the space like Evel Knievel. In No Comment, the men continually fell to the floor, as though blown down by an invisible hammer. As a finale, they stripped to their waists to reveal their glistening muscular torsos. Like fight club winners, they took their bows. But their message—sex objects who pulverize themselves are cool—confounded me.

Visions of aggression and angst trumped visions of cooperation and kindliness in the three FFD programs of 12 dances from 12 international and national-based companies seen on September 28 and 30, and October 13. Perhaps the programming, spearheaded by artistic advisor Stanford Makishi, not only represented his personal preferences, but also reflected the times. The majority of the works were made in the past four years, and only two dated before 2002. This decade hasn’t been an easy ride; the dances reflects that.

The festival’s first program ended with Martha Graham’s Chronicle, which was made in response to rising European fascism before World War II. The first section of Graham’s 1936 work surprisingly echoed the last work in the festival: Deseo Y Conciencia (2011). In Deseo, flamenco choreographer-performer Maria Pagés donned a red costume that transformed into a shroud. Likewise, the gargantuan red underskirt worn by Blakeley White-Mcguire in Chronicle possessed the same import. Both women became symbols of mourning, evoking through their blood-red cloaks a fraught world.

Maria Pages. Photo by David Ruano

Blakeley White-McGuire. Photo by Michele Ballantini

The two most ambitious works, of the 12 viewed, were Pam Tamowitz’s Fortune (2011) and Christopher Wheeldon’s Five Movements, Three Repeats (2012). Both tendered subtlety, nuance and mystery. (Full disclosure: Fortune was choreographed on the Juilliard School dancers and I work at Juilliard.) In Fortune, Tamowitz set 21 dancers, costumed in hot pink and red unitards, against a field of greenish yellow. Here was a happy Mark Rothko painting. Though Tamowitz’s movement vocabulary is clearly inspired by Merce Cunningham’s, she doesn’t ignore the music as was Cunningham’s way. Tamowitz’s sharply sculptural patterning, full of pregnant pauses, reflected Charles Wuorinen’s stop and go Fortune (performed by a quartet Juilliard School musicians). In response to Wuorinen’s abrupt shifts in sounds, which instantly dissolve as though they never happened, Tamowitz evokes mini narratives, some absurd, others resonant of a city life, where pedestrians walk with laser-eye certainty.

Juilliard Dancers in "Fortune." Photo by Rosalie O'Connor

Also of note was Christopher Wheeldon’s Five Movements, Three Repeats, which was made for Fangi-Yi Sheu & Artists. Sheu, a former Graham dancer born and trained in Taiwan, is now based in New York. She is one of the great performers of our time. Her guests were none other than Wheeldon’s former colleagues at New York City Ballet: Tyler Angle, Craig Hall and Wendy Whelan. To a recording of Max Richter’sMEMORYHOUSE and Otis Clyde’s The Bitter Earth/On the Nature of Daylight, Wheeldon didn’t treat Sheu as some modern dance oddity among the City Ballet dancers.

At the beginning of every other section of Five Movements, Three Repeats, Sheu undulated her spine like a fern seeking light. Her pliable torso work was best picked up in Hall’s simultanesously-occurring solo that spiraled into the floor. Later on, Sheu and Hall folded their limbs into each other. Their duet featured a melding of their bodies, and organically blended central aspects of their different technical training (Sheu’s focuses on weight, Hall’s on ethereality).

Ms. Sheu and Mr. Hall. Photo by Erin Baiano

Though Sheu’s legwork is akin to the arrow-like esthetic favored by ballet choreographers, Wheeldon didn’t devolve to his usual histrionics: over-choreographing women’s leg extensions in the pas de deux. Consequently, Sheu did not become a human gumby. Instead, she partnered Hall’s weight as much as Hall partnered her’s. Wheeldon’s venture into making work for a modern-trained dancer is heartily welcome. The task seems to stretch him instead of over-stretching his female collaborators.

Tags:Blakeley White-Mcguire, Charles Wuorinen, Christopher Wheeldon, Chronicle, Circa, Craig Hall, Deseo Y Conciencia, Evel Knievel, Fall for Dance Festival, Fang Yi-Sheu, Five Movements Three Repeats, Fortune, LPD-Laboratory Dance Project, Maria Pages, Martha Graham, Max Richter, Memoryhouse, Merce Cunningham, No Comment, Otis Clyde, Pam Tamowitz, Stanford Makishi, The Bitter Earth/On the Nature of Daylight, The Juilliard School, Tyler Angle, Wendy Whelan, Yaron Lifschitz

Posted in The Torn Tutu | Comments Closed