By Rachel Straus

Adam Barruch’s I Had Myself a True Love had my vote as the winner of the DanceNOW Challenge at Joe’s Pub. On September 5, Barruch’s competition was nine other choreographers. Just like a prime-time dance competition, the sold-out audience was invited to judge and pick a favorite. The challenge for the artists was to create a work in under five minutes for the tiny cabaret stage which provides, in the words of producer Sydney Skybetter, “a clear concise artistic statement.” The odds were tipped toward Barruch. He was the only choreographer with two works on the program. Last year he was a DanceNOW winner. This year his new hyper-expressive solos to recorded music sung by Barbara Steisand opened and closed the hour-long evening.

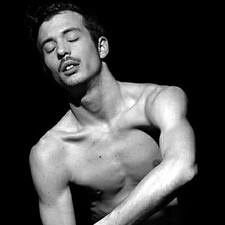

At the smartly renovated Joe’s Pub, the boyish-looking Barruch danced from the gut. But his work wasn’t sentimental. It was intentionally overwrought. Like Pina Bausch, Barruch contasts sharp, vexed gestures with voluminous ones that wash over his body like a tidal wave. His small gestures—wrists curling up like a fern, fingers streching the lids of his eyes wide—become the places where Barruch dances a specific experience. To me it read as if he was seeing a horror and longing to transcend it. Barruch’s transcendence occurred through his loose-limbed body’s swirling and lunging and his speed that left behind distinct lines in space, like that of a painter’s brush. Barruch’s choice of Streisand songs I Had Myself a True Love and Lover, Come Back To Me grounded the two solos in a narrative. But unlike many Streisand dance tributes, Barruch’s didn’t stoop to camping this favorite diva. Instead, he channelled Streisand’s intensity and oddness through Charlie Chaplin-like facial expressions that expressed forlornness, hope and near madness.

Barruch studied for a year and a half at The Juilliard School and then launched himself as a choreographer-dancer in today’s hard knocks dance world. Multiple dance educational institutions have commissioned him to teach and make works. He has been a stand out in several group shows. Recently, the Alvin Ailey Foundation’s New Directions Choreography Lab invited him to be one of their initiative’s first recipients. Barruch is getting noticed.

As for the other artists, they made for an eclectic evening. Some were funny, others were earnest. If you feel like seeing new dance-theatre makers and voting for your favorite one, DanceNOW’s tenth anniversary Joe’s Pub festival continues (September 6, 7, 8 and 15). Producer-directors Robin Staff, Tamara Greenfield and Sydney Skybetter will help choose an overall winner of the DanceNOW Challenge. That artist will receive $1,000, a week-long creative residency, and twenty hours of New York City studio space. This prize is not Lotto, but these days dance artists need all the bits of help they can get.