By Rachel Straus

Most dancers’ careers last a little more than a decade. José Manuel Carreño’s reached the quarter century mark this year. The Cuban-born and trained principal dancer announced his retirement with American Ballet Theatre in September 2010. On June 30, to a full-capacity audience at the Metropolitan Opera House, Carreño made his farewell performance, dancing Prince Siegfried in Kevin McKenzie’s staging of Swan Lake.

Carreño’s departure from ABT marks the passing of a notable generation of performers. Their task was not easy. They danced at the end of the American dance boom in works by renowned ballet choreographers who had made or were making their last dances. Carreño never worked with George Balanchine, Frederick Ashton, Kenneth MacMillan, Antony Tudor, and Jerome Robbins, though he danced their ballets exquisitely. He modeled himself after Mikhail Baryshnikov, Rudolph Nureyev, and Eric Bruhn (who danced with Carreño’s teacher Alicia Alonso, longtime director of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba). Carreño, however, never attained these male dancers’ beyond-the-ballet-world stardom. “Shit—why didn’t I keep playing baseball?” Carreño recently said to Time Out dance columnist Gia Kourlas. Carreno’s comment was a joke. His calling card has been his unswerving passion for ballet.

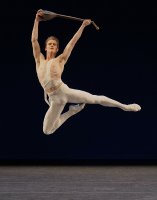

In an era marked by critics, choreographers, and dancers looking over their shoulders at a passing golden age, Carreño’s confident, uncomplicated stage presence reassured. He gave himself to his roles and his partners completely. As Prince Siegfried, Carreño demonstrated his gallant charms. They include his virtuoso technique (following four pirouettes, he balanced in near stillness before lowering his working leg to the floor), his panther-like grace (turning in mid air, his legs scissored behind him, then in front), and his winning smile.

Like most farewell performances, Carreño’s was as much about honoring his career as highlighting the careers of dancers who are in their prime. Carreño presented each of these performers to the audience with a graciously extended arm. Up first was Joaquin De Luz (as Benno, the prince’s friend). A New York City Ballet principal, De Luz’s guest artist appearance marked the first time he has danced with ABT since he left the company in 2003. In Act I’s Pas de Trois, De Luz, Sarah Lane and Yuriko Kajiya rode the full-bodied symphonic quality of Tchaikovsky’s music (under the baton of Ormsby Wilkins) with a what-me-worry charisma.

Other dancers in their prime, who performed, were David Hallberg (as the evil sorcerer von Rothbart) and Gillian Murphy. Both wowed. Murphy danced Odile (the black swan) while veteran ballerina Julie Kent performed Odette (the white swan). This splitting of Swan Lake’s lead female role isn’t unknown. It was, however, made through Carreño’s suggestion and casting. The contrast between Murphy and Kent’s performances was the most interesting part of the evening. Kent, who like Carreño has 16 years with ABT, unfolded her limbs as though they were tendrils. Her delicacy is her signature quality. It is also a product of her age. Murphy, in contrast, eats up space. She dances with a juicy, full-bodied, fearless quality. This ballerina is no waif.

But it was David Hallberg’s presence that radiated the strongest, if acting as much as dancing is the Geiger counter test. Appearing in Act III, Hallberg as Von Rothbart bore into his fellow performers eyes’ like kryptonite. He danced with each of the four Princesses, luring them into his orbit like a menacing rake that you just can’t help but like. With the Queen Mother (Susan Jaffe), he led her back to her throne and impudently sat in Prince Siegfried’s throne. Hallberg’s comic chutzpah stood in stark contrast to Carreño’s noblesse oblige, which is all to the good, if one believes that von Rothbart and the Prince are foils to Odile (who is imprisoned into the body of a swan by Rothbart and is further condemned by the Prince’s pledge of love to Odette).

Unlike Hallberg, Carreño’s performance wasn’t that memorable. Perhaps it was because McKenzie’s staging of Swan Lake, after Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov, isn’t that satisfying. There are too many choreographic and visual elements that don’t gel. One occurs when Carreño and Kent leap to their deaths. They look like flying fish rather lovers sacrificing their mortality to be with each other in the afterlife. Another concerns Zack Brown’s Cecil B. DeMille style backdrop from Act III. It bears resemblance to the technicolor scene in The Ten Commandments when Moses parts the Red Sea. Hollywood’s bombastic sensibility rules in Mckenzie’s version, which Carreño has performed since its 2000 New York premiere.

As flowers rained down onto the stage, Carreño took his final bows. A Moses-like parting of the ways occurred. While his colleagues will continue their ballet performance careers, Carreño will cross over to teaching and coaching. He will help usher in the next generation. No doubt he’ll do it with unswerving dedication.