by Cathy Barbash

I had coffee recently with a new acquaintance, Linda Lee. A Hong Kong native and former Director at Burson Marsteller and Shanghai correspondent for CNBC Asia, Lee now hosts a weekly informal professional workshop in Chinese improv in Beijing as an adjunct to her professional training consultancy. Traditionally, verbal communication, both business and personal, is highly premeditated and structured. “Chinese people doesn’t open their mouths, even to speak to family members, unless they have mentally played out the ramifications of their statements several moves out, like a chess game,” explained one of my closest Chinese friends in my early days working in China. (This was the Chinese way of telling me to keep my big mouth shut…) At conferences, Chinese speakers invariably read from prepared remarks that participants will find already included in their folders. Chinese comedy still tends to the structured; the cross-talk routines remind me of Abbott and Costello’s “Who’s on First?”

The Monday evening classes are strictly Chinese language, and aimed at both human resource professionals and low and mid-level employees wishing to improve their self-confidence. Participants now include bank and government employees and others attracted through postings on Chinese social networking websites. They aim to hold their first workshop performance this fall to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the foundation of the People’s Republic of China, and hope eventually to expand the program into Chinese schools.

“People’s initial reaction was “What is improv?” explained Lee. “The Chinese mind is indirect, so this is an education in stretching them. Improv is direct, you must learn to be confident with each other, and this provides a safe and spontaneous way to learn.”

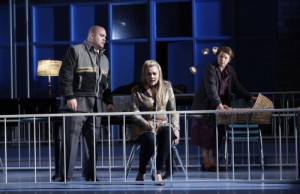

Thus another art form very foreign, even anathema to the Chinese ethos, seeps in. Will aspiring Chinese professionals take to improv as ambitious Chinese youth first took to piano lessons? Last year’s first annual Improv Festival at the Penghao Theatre (see July 7 post) attracted 300 people with little publicity. Look for the second installment in Spring 2010. However, in a society that prefers predictability and control, I wouldn’t bet that we’ll enjoy Second City-style improv on the CCTV Chinese New Year’s Show in our lifetime.