By Brian Taylor Goldstein, Esq.

I haven’t found an example that matches the situation of a 501(c)(3) I am familiar with. They throw a once-yearly art festival that spans a weekend (2days). They don’t charge the public any admittance. They raise money by charging fees for booth (10×10) spaces for (visual) arts vendors to sell their merchandise. They raise money for: their operating expenses, student art scholarships, member art scholarships, honoraria for program presenters at meetings, a fund for a permanent “home” for the 501c3 where they can hold meetings and store various gear for the meetings between times. They also have an open air music stage at that festival where local musicians perform. The musicians are paid under $150.00 for a 2 hour performance that includes 5 minutes each for set-up, a break, and stage clear-off. Most, but not all of the pieces performed are written by the performers. The “audience” is anyone who wanders by and stays to listen for a while. So, who, if anyone, has to pay fees to the likes of ASCAP, BMI, etc.?

It sounds like the 501(c)(3) organization in your scenario is trying to raise money for some very admirable and worthy goals: art scholarships, arts education, and even providing a place for local musicians to perform. In fact, these goals sound so worthy that I’m sure you wouldn’t object to the organization using your house for meetings or taking your car whenever they needed it to transport students to art classes, all without your permission and without paying you any fees. While you might be more than willing to donate your home or car on occasion, my suspicion is that you’d at least like to be asked first. As a general rule, the involuntary donation of other’s property without their permission—even if it’s for a really good cause—is also called “stealing.”

A musical composition—just like a home or a car—is considered property. It is no less valuable—indeed, I would argue, it is of greater value—than anything else you are required to pay for that has a physical price tag attached. A musical composition belongs to the composer who wrote it and/or the composer’s publishing company. Under U.S. Copyright Law, whoever owns a musical composition also has the absolute right to control and determine all uses of the property—this includes the right to perform the music live, record the music, play a recording of the music for the public, change the lyrics, make arrangements, or just about anything else you can think of to do with music; including the right to determine whether or not to donate the use of the composition for a worthy cause or project.

This means that any time a musical composition is performed live or a recording of the composition is played—whether it’s at a theater, concert hall, or out-door street festival (for-profit or non-profit)—“someone” needs to obtain the composer’s permission and, in most cases, pay a usage fee called a “Performance License.” ASCAP, BMI and SESAC are not roving bands of brigands waiting to pounce on unsuspecting non-profits who are merely trying to promote the arts. Rather, these organizations are trying to promote the arts too—primarily by reminding people (including other artists) not to take music for granted as a valueless commodity. ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC are organizations that represent composers, issuing performance licenses and collecting fees on their behalf.

If musicians are performing original music they composed themselves, then they can certainly agree to perform their own music for free. That can be a condition of hiring them to perform in the first place. However, if a musician or band is playing (“covering”) music composed by others, then just because the musicians agree to perform for a reduced fee, or even for free, doesn’t mean that the composers have allowed their music to be performed for free as well. A performance requires a performance license.

As for whose responsibility it is to obtain the necessary license, its legally everyone’s responsibility. If an unlicensed song is performed at a festival (even a free festival), then the U.S Copyright Act allows all the parties involved in arranging the performance—the artist as well as the venue or festival, and sometimes even the promoter, producer, or booking agent—to be liable for copyright infringement. So, while you could require the musicians to obtain their own licenses with regard to any music they are performing which they have not composed themselves, in my opinion that is a foolish policy. Why? Because most musicians will simply not bother and elect to take the risk of not getting caught. However, if they do get caught, it is the venue or festival who will be liable as well. It doesn’t matter that the festival may have required another party to obtain the license. That simply entitles the festival to sue the other party. The festival itself will remain liable to the composer.

So, in your case, while there are a number of factors that can determine the cost of obtaining performance licenses—the size of the venue, the price of tickets (or lack thereof), the number of performances, etc.–ultimately, it’s in the festival’s or organization’s best interest to ensure that the necessary permissions and licenses are obtained. While it might be tempting to proceed under the expectation that no one will get caught or the publishers and copyright owners will not sue small artists or struggling non-profits, that’s the same as robbing a bank and hoping the police won’t find you. Not to mention, in an industry where so many purport to operate under the noble purpose of promoting the value of art and artists, I can’t imagine the rationalization of stealing it for any purpose, regardless of how noble.

__________________________________________________________________

For additional information and resources on this and other legal, project management, and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

legal, project management, and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

To ask your own question, write to lawanddisorder@musicalamerica.com

All questions on any topic related to legal, management, and business issues will be welcome. However, please post only general questions or hypotheticals. GG Arts Law reserves the right to alter, edit or, amend questions to focus on specific issues or to avoid names, circumstances, or any information that could be used to identify or embarrass a specific individual or organization. All questions will be posted anonymously and/or posthumously.

__________________________________________________________________

THE OFFICIAL DISCLAIMER:

THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE!

The purpose of this blog is to provide general advice and guidance, not legal advice. Please consult with an attorney familiar with your specific circumstances, facts, challenges, medications, psychiatric disorders, past-lives, karmic debt, and anything else that may impact your situation before drawing any conclusions, deciding upon a course of action, sending a nasty email, filing a lawsuit, or doing anything rash!

Mozartwoche: January’s Peace

Monday, February 15th, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 15, 2016

SALZBURG — There is a pleasure in arriving in Salzburg with snow on the ground. Or maybe the word is reassurance: the city will be real, not a theme park; the people mostly locals, despite the hollowing out of property ownership here; the profile quiet, even intimate, affording a chance to connect with the past. Of Salzburg’s festivals, the snowiest inevitably is Mozartwoche, planned and manned by the Mozarteum to straddle the composer’s birthday, often by more than a week. Last year’s edition achieved a coup by returning horses to the Felsenreitschule, for Davidde penitente as realized by “French equine artist and theatrical genius” Bartabas; next year, managers Marc Minkowski and Matthias Schulz let Bartabas loose on Mozart’s Requiem (Mel Brooks having declined) and promise some thirty concerts besides, including three by the Vienna Philharmonic, with Haydn as “focus composer.”

Mozartwoche 2016, placing Mendelssohn in focus, opened Jan. 22 with spoken words lauding the long contribution of Nikolaus Harnoncourt not only to Mozart’s music but specifically to this festival, where he was again due to conduct before declaring several weeks ago his instant retirement. The packed day teamed Katia et Marielle Labèque with the Mozarteum-Orchester in the morning, continued at 3 p.m. with an András Schiff recital, and ended soberly with Mozart masses at the Großes Festspielhaus led by John Eliot Gardiner. Rewards were many, irritations few.

The matinee sorely needed a conductor to temper dynamics and coordinate the shaping of lines. Where was Ivor Bolton? It began with a Mendelssohn Trumpet Overture (MWV P2, 1826) that knew no piano. Next came Mozart’s E-flat-Major Concerto for Two Pianos (1781) and chronically clunky phrasing by the French sisters; this was redeemed somewhat by a neatly sprung Rondo. Quality rose with a still loud, yet spry, Schauspieldirektor Overture (1786), the music’s inventiveness laid out vividly. The teenage exuberance of Mendelssohn’s Concerto in E Major for Two Pianos (MWV O5, 1823), in conclusion, proved a good match for the Labèques; alas they then imposed a duo encore (and an insipid one, the last of Glass’s Four Movements for Two Pianos, 2008) to ruin our exit.

The Mozarteum’s Conrad-Graf-Flügel and Walter-Hammerflügel (1839 and 1782) stood side by side on the platform for Schiff’s recital. Mendelssohn came first: the Variations sérieuses (1841) and the F-sharp-Minor Sonate écossaise (1833), played on the later instrument with its charming pearly highs and fuzzy, attenuated lows. Schiff made inspired sense of the lines in both works and bound Mendelssohn’s ideas together expertly without shying from a breakneck pace where needed. The Walter’s clarity and evenness through the range made a stark contrast, its modest sound easy to settle into in this artist’s hands. Ideal tempos and immaculate voicing sustained Mozart’s late major-key sonatas, in C (für Anfänger), B-flat and D; the poise of Schiff’s playing overcame passing glitches.

Gardiner’s highly musical, not especially spiritual, reading of the Große Messe K427 (1783) closely resembled the adjusted Aloys Schmitt reconstruction he recorded in London decades ago. His crisp rhythms and airy textures, and the way these flattered the score’s abundant lyricism, seemed designed to please, as if Mozart had composed the truncated service just for today’s Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists. From this listener’s seat, vocal soloists Amanda Forsythe, Hannah Morrison (sopranos), Gareth Treseder (tenor) and Alex Ashworth (bass) could not be seen or properly heard, but the choir, also mostly out of view, sounded disciplined. Orchestrally it was a performance with resilience, wary balances, individual style; veteran sackbuttist Stephen Saunders managed to nod off during Forsythe’s Et incarnatus est, nearly losing his instrument off the riser’s edge. A horseless Mozart Requiem followed the break; for practical reasons we could not stay.

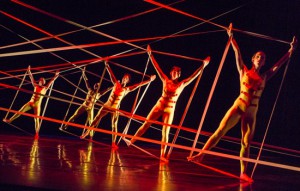

Photo © Tourismus Salzburg

Related posts:

Salzburg Coda

Horses for Mozartwoche

Mariotti North of the Alps

A Stirring Evening (and Music)

Maestro, 62, Outruns Players

Tags:András Schiff, Bartabas, Commentary, English Baroque Soloists, Felsenreitschule, Großes Festspielhaus, John Eliot Gardiner, Katia et Marielle Labèque, Mendelssohn, Monteverdi Choir, Mozarteum, Mozarteumorchester, Mozartwoche, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Piano, Review, Salzburg, Sonate écossaise, Variations sérieuses, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed