By ANDREW POWELL

Published: August 7, 2016

MUNICH — Two evenings after an “Allahu Akbar” eruption here cost nine mostly teenage, mostly Muslim, lives, it felt perverse to indulge in 280-year-old French escapism stretching to Turkey, Peru, Iran and the future United States.

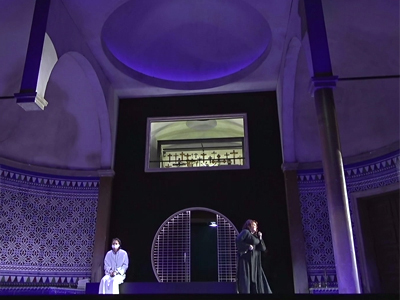

But there we were July 24 in the Prinz-Regenten-Theater for Bavarian State Opera business-as-usual, a festival yet, and Rameau’s four-entrée Les Indes galantes as imagined by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, the Belgian choreographer with stage-director pretensions.

And safer we were, too, than at a smaller music festival 110 miles away near Nuremberg, the outdoor Ansbach Open, where a Syrian refugee denied asylum in this country was preparing to explode his metal-piece-filled backpack among two thousand listeners. (As luck would have it, Germany’s first suicide bomber killed only himself when he detonated only his detonator and did so outside the festival’s gates, not having known in advance he would need a ticket.)

Before departing for Turkey, the opéra-ballet states its premise by means of a prologue: European lovers pressed to exchange Goddess Hébé’s doux instants (sweet moments) for Goddess Bellone’s gloire des combats can count on intercession from a third god, Amour, as they “traverse the vastest seas” in military service.

This plays out with amusing dramatic variance* in the four locales to music of beguiling harmony and bold instrumental color, in airs, vocal ensembles, choruses and dances. The U.S. entrée concludes with the Dance of the Great Peace Pipe (penned after Agapit Chicagou’s 1725 Paris visit), minuets, a gavotte, and a most charming chaconne.

If you kept your eyes closed, the performance was a treat. Opening them invited confusion, or worse, despite Cherkaoui’s fresh dance moves, tirelessly executed by his Antwerp-based Compagnie Eastman.

Ivor Bolton and the Münchner Festspiel-Orchester, an elite Baroque pick-up band, served Rameau with verve and expressive breadth, ripe string sound and fabulous wind playing. The Balthasar-Neumann-Chor from Freiburg managed its musical challenges neatly, in opaque French.

The score’s 17 roles went to ten generally stylish soloists. Lisette Oropesa proved a graceful musician in the lyric soprano duties of Hébé and Zima. Anna Prohaska, as Phani and Fatime, stopped the show with a divinely phrased Viens, Hymen, viens m’unir. Light tenor Cyril Auvity sang artfully as Valère and Tacmas, while John Moore’s baritone lent a golden timbre to the sauvage Adario. Reveling grandly in the music’s depths were basses François Lis (Huascar and Alvar) and Tareq Nazmi (Osman and Ali).

But soprano Ana Quintans encountered pitch problems as Amour and Zaïre; Elsa Benoit, the Émilie, seemed squeezed by Rameau’s nimble turns; Mathias Vidal pushed harshly for volume in the tenor roles of Carlos and Damon; and bass Goran Jurić, in drag as Bellone, muddied her vital rousing words.

As for the staging, new on this night, conceit and a ruinous idea got the better of Cherkaoui (and BStO managers, who should have intervened if they care about Baroque opera as they profess): he would thread together the prologue and entrées into one dramatic unit. Characters would appear in each other’s sections, mute. Opéra-ballet form be damned.

In place of exotic lands (requiring exotic sets and costumes), the viewer would journey from schoolroom to museum gallery to church to flower shop, to no place, to some closed border crossing. The spectacle of Peru’s Adoration du Soleil, for instance, would unfold in the church. Woven throughout, clumsily, would be tastes of the plight of Europe’s present refugees, and Europeans’ poor hospitality. Count the ironies.

[*In Turkey a melodrama, as the shipwrecked lovers’ fate turns on Osman’s magnanimity (Le turc généreux). In Peru a tragedy, as the couple’s freedom results from Huascar’s molten-lava death (Les incas du Pérou). In Iran a bucolic, as two pairs of lovers ascertain their feelings through disguise and espial (Les fleurs, original version of Aug. 23, 1735). In the U.S. a comedy, as noble savage Zima flirts with and mocks two European colonists, reversing the pattern, before homing in on loving native Adario (Les sauvages).]

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Portraits For a Theater

Nitrates In the Canapés

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Blacher Channels Maupassant

On Wenlock Edge with MPhil

Mohammed Fairouz, born in 1985, is one of the most frequently performed, commissioned, and recorded composers working today. By his early teens, the Arab-American composer had journeyed across five continents, immersing himself in new sounds and experiences. His catalog encompasses virtually every genre, including opera, symphonies, vocal and choral settings, chamber and solo works. His voice as a composer is personal, filled with imagination and surprises.

Mohammed Fairouz, born in 1985, is one of the most frequently performed, commissioned, and recorded composers working today. By his early teens, the Arab-American composer had journeyed across five continents, immersing himself in new sounds and experiences. His catalog encompasses virtually every genre, including opera, symphonies, vocal and choral settings, chamber and solo works. His voice as a composer is personal, filled with imagination and surprises.