By ANDREW POWELL

Published: January 27, 2017

ZURICH — It was not the most natural of programs. Beethoven’s familiar C-Major Piano Concerto (1795) prepared nobody for Éclairs sur l’Au-Delà … , or Lightning Over the Beyond … , the 65-minute theological ornithological astronomical would-be symphony Messiaen finished in 1991. Wary of the exotic fare ahead, many in the Tonhalle-Orchester’s subscription audience here Jan. 7 left at intermission. Others returned to their seats only to grow restless as Éclairs unfolded, and they then feet-shuffled and door-slammed between its movements. Maestro and program architect Kent Nagano maintained his serenity nonetheless, all the way through.

Daniil Trifonov turned in a leaden, joylessly intense reading of the concerto, nowhere near Beethoven’s world. He reduced the solo part to a stilted struggle of his own devising, albeit a sincere one masterfully played. He overstated dynamic contrasts within phrases, creating alien shapes. The first movement, played slowly, essentially lacked a pulse; Nagano began it in that manner, evidently at his soloist’s behest. As Trifonov’s sweaty bangs swished near Steinway’s S&S logo and his chin hovered just above the backs of his hands, he telegraphed a crazily forced disquiet. The second movement sounded numb. Life emerged, somewhat, in the crowd-pleasing Rondo.

Messiaen’s opus summum in its Zurich premiere wound up defying the defectors and sent most listeners home with the spiritual boost its writer must have intended — at least if their spirited applause was any sign. The performance confirmed Messiaen’s wisdom in scoring, sequencing, and above all timing his material so as to build a coherent and moving structure, even as he sought the most divergent attributes for his eleven movements.

There is no climax. Instead, the eighth movement, employing 128 musicians, anchors Éclairs by recognizing every strand of thought it possesses, and the plush string harmonies of the last movement bring the composer to his point (and his title): a glimpse of the Celestial City, the Au-Delà, made possible by shafts of lightning, the Éclairs. It is a “journey,” one decorated in seven of the movements with birdsong from 48 species — a trait that separates it from its closest cousin in Messiaen’s canon, the Turangalîla-Symphonie, which is somewhat longer with one movement less.

The Tonhalle-Orchester balanced an astonishing range of sonorities, neatly intoning the unison passages, diligently tracing the glissandos and melismas, and somehow preventing the textural lurches between movements — and between ideas within them — from undermining Messiaen’s last, vast statement on mortality. Nagano favored a brisk pace overall and cued the vital bird entrances with fanatical clarity.

Tempo can be conjectural in Messaien, properties varying, and Éclairs has been no exception over the years. Nagano on this occasion came close to Simon Rattle’s workaday 61 minutes, as recorded in Berlin in 2004. But Sylvain Cambreling’s diligent 2002 Freiburg recording spreads to 75 minutes. Myung-Whun Chung, who worked with Messiaen on a benchmark 1990 recording of Turangalîla, taking 78 minutes for that work, completes Éclairs in a middling 65 minutes on his 1993 Paris disc, yet his view is not especially compelling.

There is one great recording of Éclairs sur l’Au-Delà … . In fact it is an essential disc for any Messiaen collection: a live 2008 performance complete with coughs and moments of shaky brass intonation on the Kairos label. Listening, one cannot imagine that anyone walked out in the middle, such is the joy and focus in the Vienna Philharmonic’s music-making. Ingo Metzmacher adopts moderate tempos (running to 67 minutes) and allows the intervals of silence to tell, but he presses on between movements, creating a palpable sense of urgency and spontaneity. His third movement, devoted to birdsong, is exhilarating. In the fifth, the Vienna strings flatter Messiaen’s long and soaring lines. Metzmacher seems to channel Mussorgsky in the fully scored eighth, and in the ninth he secures the most vivid demonstration — possibly ever recorded — of Messiaen birdsong. From his abode in the Celestial City, the composer will have been pleased.

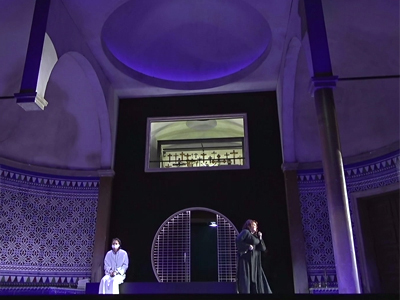

Photo © Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich

Related posts:

Winter Discs

Salzburg Coda

Horses for Mozartwoche

Written On Skin, at Length

Munich Phil Tries Kullervo