By Brian Taylor Goldstein, Esq. I am writing you about a question we have in regards to the length of stay that USCIS grants for O-1B visas. In the past few years, it has been our experience that USCIS will not grant 3 year visas for a time period that has gaps from anywhere to 3 to 6 months between engagements. Therefore, for our artists, we have been applying for month long visas, or three month long visas, etc, which has started to become prohibitively expensive for them, and rather inconvenient and time consuming for us. We were told by an artist that is moving off of our roster that his new manager will be applying for a 3 year visa for him, regardless of the fact that this particular artist has gaps of 6 or more months between engagements, or no engagements at all after a certain point. So our question is, has the USCIS policy changed, or worse, do you think it’s possible that the artist’s new manager has some kind of connection or agreement with USCIS that we do not? Artist visas are not defined by length, but by type: O-1 visas for individual artists, P-1 visas for groups, and P-3 visas for culturally unique individuals or groups. The length of the visa validity period depends on how many engagements and other activities (rehearsals, production meetings, receptions, etc) the artist or group has in the United States—up to 1 year of engagements for P visas and up to 3 years of engagements for O visas. Officially, USCIS will approve a single visa validity period where all the engagements constitute “a continuous event”, such as a tour. However, in its inimitable predilection for unhelpfulness, USCIS has no specific definition of “a continuous event” and no policy on the minimum or maximum length of “gaps” between engagements and activities. Rather, USCIS examiners are given complete, unfettered discretion when it comes to determining whether a gap between engagements is too long and will require filing separate petitions. Let’s say, for example, that an artist has an engagement in October 2013 and their next US engagement is not until April 2013 and the manager files a visa petition requesting a validity period of October 2013 through April 2013. USCIS could either approve the visa for the entire length of the validity period requested, notwithstanding the six month gap between engagements, or it could only approve enough time to cover the October 2013 engagement and require the manager to file a new, separate petition for the April 2013 date. When dealing with this issue, anecdotal evidence and actual experience is your best guide. While I have known USCIS to approve visa petitions even with large gaps between engagements, more often than not it will “cut off” a visa validity period where there are more than 3 – 4 months between engagements or activities. My general advice is to keep gaps as short as possible. As for shortening gaps, or even extending the length of an entire visa validity period, consider this: you are not limited to including in your visa petition only engagements dates that have signed engagement contracts. You do not have to provide a signed contract to support each engagement. Instead, USCIS will accept any written confirmation of an engagement, including unsigned term sheets, deal memos, emails, confirming letters. Even if a date is still under negotiation, so long as you are holding that date on the artist’s calendar, it can be including on the visa petition along with an accompanying written confirmation that the date is being held. In addition, you can also provide a list of the artist’s non-US engagements and explain that when the artist is not performing in the US it is because the artist will be performing elsewhere in the world. I can assure you that USCIS has no special deals with your ex-artist’s new manager. According to your question, your ex-artist is merely claiming that his new manager “will be applying” for a 3 year visa for him. “Will be applying” is not the same that as “has obtained.” If the artist has large gaps in his itinerary or lacks 3 years of engagements, he will be receiving a Request for Evidence (RFE) or a visa denial, not an O-1 with a validity 3 years. Don’t believe everything you are told, especially by disgruntled ex-artists who want you to believe they have moved to greener pastures. __________________________________________________________________ For additional information and resources on this and other legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com To ask your own question, write to lawanddisorder@musicalamerica.org. All questions on any topic related to legal and business issues will be welcome. However, please post only general questions or hypotheticals. GG Arts Law reserves the right to alter, edit or, amend questions to focus on specific issues or to avoid names, circumstances, or any information that could be used to identify or embarrass a specific individual or organization. All questions will be posted anonymously. __________________________________________________________________ THE OFFICIAL DISCLAIMER: THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE! The purpose of this blog is to provide general advice and guidance, not legal advice. Please consult with an attorney familiar with your specific circumstances, facts, challenges, medications, psychiatric disorders, past-lives, karmic debt, and anything else that may impact your situation before drawing any conclusions, deciding upon a course of action, sending a nasty email, filing a lawsuit, or doing anything rash!

Visa Envy: Why Is Yours Longer Than Mine?

July 31st, 2013Partial View

July 25th, 2013by Sedgwick Clark

I wandered over to Lincoln Center on Wednesday to see the opening act of Kronos Quartet’s five-night 40th-anniversary gig. Mark Dendy’s new site-specific modern-dance work for 80 dancers, Ritual Cyclical, was being staged in and around the Henry Moore reflecting pool in front of the Vivian Beaumont Theater and set to Kronos recordings on Nonesuch. The Times had given a big spread to it on Monday the 22nd, dominated by a dramatic photo of two dancers in the pool in a balletic pose. Alas, by the time I arrived there were so many people standing on the plaza around the pool that only the tops of the sculptures were visible, and attempting to walk around for a different view without seeming pushy was not possible.

After about half an hour several disagreeable-looking women dressed in army fatigues cleared out a circular area between the pool and Avery Fisher Hall so that a few dancers could run around gazelle-like in an effort to open up the available stage area, but the most interesting choreography presumably was out of view for all but those lining the pool. Eventually, for some reason, the crowd began to shift toward Alexander Calder’s Box Office sculpture in front of the Performing Arts Library entrance. The Kronos recordings, which had been easy on the ear up to this point, segued to the 1943 recording of Charles Ives playing piano and singing his antiwar song They Are There, followed by Jimi Hendricks’s electronically distorted arrangement of Kronos scratching out The Star-Spangled Banner – a rendition that makes Roseanne Barr’s infamous 1990 San Diego Padres pre-game performance seem mellifluous by comparison – and the audience quickly thinned out.

Bard Festival’s Stravinsky Weekends

There’s been a lot of Stravinsky in this blog so far this year, and there will be more as the world continues to celebrate the centennial of his Le Sacre du printemps. Those who share my passion for his music and wish to hear other composers’ works from the same period as well should comb the schedule of events below and plan to be at the Bard Music Festival in Annandale-on-Hudson, August 9-11 and August 16-18.

Program details of Bard Music Festival, “Stravinsky and His World”

WEEKEND ONE: Becoming Stravinsky: From St. Petersburg to Paris

Friday, August 9

PROGRAM ONE

The 20th Century’s Most Celebrated Composer

Sosnoff Theater

7:30 pm Pre-concert Talk: Leon Botstein

8 pm Performance: Alessio Bax, piano; Andrey Borisenko, bass; Lucille Chung, piano; Kiera Duffy, soprano; Gustav Djupsjöbacka, piano; John Hancock, baritone; Melis Jaatinen, mezzo-soprano; Anna Polonsky, piano; Mikhail Vekua, tenor; Orion Weiss, piano; Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director; members of the American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music directorIgor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Les Noces (1914–17)

Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1920, rev. 1947)

Symphony of Psalms (1930)

Concerto for Two Pianos (1935)

Abraham and Isaac (1962–63)

Tickets: $25, $35, $50, $60

Saturday, August 10

Panel One

Who Was Stravinsky?

Olin Hall

10 am–noon

Christopher H. Gibbs, moderator; Leon Botstein; Marina Frolova-Walker; Olga Manulkina; Stephen Walsh

Free and open to the public

Program Two

The Russian Context

Olin Hall

1 pm Pre-concert Talk: Marina Frolova-Walker

1:30 pm Performance: Matthew Burns, bass-baritone; Dover Quartet; Gustav Djupsjöbacka, piano; Laura Flax, clarinet; Marc Goldberg, bassoon; Melis Jaatinen, mezzo-soprano; Piers Lane, piano; Orion Weiss, piano

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Faun and Shepherdess, Op. 2 (1906–07)

From Four Studies, for piano, Op. 7 (1908)

Three Movements from Petrushka, for piano solo (1921)

Mikhail Glinka (1804–57)

Trio Pathétique in D minor (1832)

Alexander Glazunov (1865–1936)

Five Novelettes, for string quartet, Op. 15 (1886)

Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915)

Vers la flamme, Op. 72 (1914)

Sergey Rachmaninoff (1873–1943)

Preludes, Op. 23, Nos. 8 & 9 (1901–03)

Songs and piano works by Modest Mussorgsky (1839–81), Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840–93), Nikolai Medtner (1880–1951), and Mikhail Gnesin (1883–1957)

Tickets: $35

SPECIAL EVENT

Film: The Soldier’s Tale

Lászlo Z. Bitó ’60 Conservatory Building

A film by R. O. Blechman, with live musical accompaniment

Tickets: $12

Program Three

1913: Breakthrough to Fame and Notoriety

Sosnoff Theater

7 pm Pre-concert Talk: Richard Taruskin

8 pm Performance: American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music director

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Fireworks (1908)

The Rite of Spring (1913)

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908)

Suite from The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh (c. 1907)

Anatoly Liadov (1855–1914)

From the Apocalypse, Op. 66 (1910–12)

Maximilian Steinberg (1883–1946)

Les Métamorphoses, Op. 10 (1913)Tickets: $30, $50, $60, $75

Sunday, August 11

Panel Two

The Ballets Russes and Beyond: Stravinsky and Dance

Olin Hall

10 am–noon

Kenneth Archer; Lynn Garafola; Millicent Hodson

Free and open to the public

Program Four

Modernist Conversations

Olin Hall

1 pm Pre-concert Talk: Byron Adams

1:30 pm Performance: Alessio Bax, piano; Lucille Chung, piano; Gustav Djupsjöbacka, piano; Kiera Duffy, soprano; Benjamin Fingland, clarinet; Judith Gordon, piano; John Hancock, baritone; Melis Jaatinen, mezzo-soprano; Sharon Roffman, violin; Raman Ramakrishnan, cello; Lance Suzuki, flute; Benjamin Verdery, guitar; Lei Xu, soprano; Bard Festival Chamber Players

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Three Japanese Lyrics (1912)

Pribaoutki (1914)

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

En blanc et noir (1915)

Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951)

Pierrot lunaire (1912)

Maurice Ravel (1875–1937)

Trois poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé (1913)

Maurice Delage (1879–1961)

Quatre poèmes hindous (1912–13)

Works by Erik Satie (1866–1925); Manuel de Falla (1876–1946); and Béla Bartók (1881–1945)

Tickets: $35

Program Five

Sight and Sound: From Abstraction to Surrealism

Sosnoff Theater�

5 pm Pre-concert Talk: Mary E. Davis

5:30 pm Performance: Anne-Carolyn Bird, soprano; John Hancock, baritone; Melis Jaatinen, mezzo-soprano; Nicholas Phan, tenor; Ann McMahon Quintero, mezzo-soprano; Anna Polonsky, piano; Orion Weiss, piano; members of the American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music director; designed and directed by Anne Patterson; projection design by Adam Larson; choreography by Janice Lancaster

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Ragtime (1918)

Mavra (1921–22)

Erik Satie (1866–1925)

Parade (1916–17; arr. piano four-hands)

Francis Poulenc (1899–1963)

Le travail du peintre, song cycle for voice and piano (1956)

Georges Auric (1899–1983), Arthur Honegger (1892–1955), Darius Milhaud (1892–1974), Francis Poulenc, and Germaine Tailleferre (1892–1983)

Les mariés de la tour Eiffel (1921)

André Souris (1899–1970)

Choral, marche, et galop (1925)

WEEKEND TWO: Stravinsky Re-invented: From Paris to Los Angeles

Friday, August 16

SPECIAL SHOWING

Filming Stravinsky: Preserving Posterity’s Image

Weis Cinema

Free and open to the public

PROGRAM SIX

Against Interpretation and Expression: The Aesthetics of Mechanization

Sosnoff Theater

7:30 pm Pre-concert Talk: Christopher H. Gibbs

8 pm Performance: Eric Beach, percussion; Judith Gordon, piano; Jonathan Greeney, percussion; Imani Winds; Piers Lane, piano; Peter Serkin, piano; Gilles Vonsattel, piano; Bard Festival Chamber Players and students of The Bard College Conservatory, conducted by Leon Botstein

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Concerto for Piano and Winds (1923–24)

Sonata for Two Pianos (1943–44)

Béla Bartók (1881–1945)

Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, Sz 110 (1937)

Edgard Varèse (1883–1965)

Octandre (1923)

Paul Hindemith (1895–1963)

Kleine Kammermusik, Op. 24, No. 2 (1922)

Olivier Messiaen (1908–92)

From Quatre études de rythme (1949–50)Tickets: $25, $35, $50, $60

Saturday, August 17

PANEL THREE

Lenin, Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini: Music, Ethics, and Politics

Olin Hall

10 am—noon

Tamara Levitz, moderator; Tomi Mäkelä; Simon Morrison; Michael Beckerman

Free and open to the public

PROGRAM SEVEN

Stravinsky in Paris

Olin Hall

1 pm Pre-concert Talk: Manuela Schwartz

1:30 pm Performance: Xak Bjerken, piano; Randolph Bowman, flute; Sara Cutler, harp; Jordan Frazier, double bass; Marka Gustavsson, viola; Robert Martin, cello; Jesse Mills, violin; Harumi Rhodes, violin; Sharon Roffman, violin; Laurie Smukler, violin; Bard Festival Chamber Players

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Les cinq doigts, for piano (1921)

Octet for Wind Instruments (1922–23)

Duo concertant (1931–32)

Albert Roussel (1869–1937)

Sérénade, for flute, harp, and string trio, Op. 30 (1925)

Bohuslav Martinu (1890–1959)

String Quartet No. 4, H. 256 (1937)

Sergey Prokofiev (1891–1953)

Sonata for Two Violins, Op. 56 (1932)

Arthur Lourié (1892–1966)

Sonata for Violin and Double Bass (1924)

Alexandre Tansman (1897–1986)

Sonatina for Flute and Piano (1925)

Tickets: $35

PROGRAM EIGHT

The Émigré in America

Sosnoff Theater

7 pm Pre-concert Talk: Leon Botstein

8 pm Performance: John Relyea, bass-baritone; Rebecca Ringle, mezzo-soprano; Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director; American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music director

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Jeu de cartes (1936)

Symphony in Three Movements (1942–45)

Ode (1943)

Requiem Canticles (1965–66)

Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951)

Kol Nidre, Op. 39 (1938)

Hanns Eisler (1898–1962), Score for Night and Fog (1955), a film by Alain Resnais

Tickets: $30, $50, $60, $75

Sunday, August 18

PROGRAM NINE

Stravinsky, Spirituality, and the Choral Tradition

Olin Hall

10 am Performance with commentary by Klára Móricz, with the Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director; Frank Corliss, piano; Bard Festival Chamber Players

Choral works by Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971); Gesualdo da Venosa (1566–1613), Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643); Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750); Sergey Rachmaninoff (1873–1943); Francis Poulenc (1899–1963), Lili Boulanger (1893–1918), and Ernst Krenek (1900–91)

Tickets: $30

PROGRAM TEN

The Poetics of Music and After

Olin Hall

1 pm Pre-concert Talk: Richard Wilson

1:30 pm Performance: Rieko Aizawa, piano; Imani Winds; Alexandra Knoll, oboe; Piers Lane, piano; Jesse Mills, violin; Bard Festival Chamber Players

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Circus Polka, arranged for piano (1942, arr. 1944)

Septet (1952–53)

Anton Webern (1883–1945)

Variations for Piano, Op. 27 (1936)

Walter Piston (1894–1976)

Suite, for oboe and piano (1931)

Aaron Copland (1900–90)

Nonet (1960)

Elliott Carter (1908–2012)

Woodwind Quintet (1948)

Ellis Kohs (1916–2000)

Sonatina for Violin and Piano (1948)

Carlos Chávez (1899–1978)

From Ten Preludes (1937)

Tickets: $35

PROGRAM ELEVEN

The Classical Heritage

Sosnoff Theater

3:30 pm Pre-concert Talk: Tamara Levitz 4:30 pm Performance: Gordon Gietz, tenor; Jennifer Larmore, mezzo-soprano; Sean Panikkar, tenor; John Relyea, bass-baritone; Bard Festival Chorale, James Bagwell, choral director; American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Leon Botstein, music director; and others

Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971)

Perséphone (1933–34, rev. 1948)

Oedipus Rex (1926–27, rev. 1948)Tickets: $30, $50, $60, $75All programs subject to change.

A Room With A View…and a 1099

July 24th, 2013By Robyn Guilliams Dear Law and Disorder, I have been in artist management for a long time, thought I had seen it all, but something just came up for one of my artists that has me completely stumped. My client was sent a 1099 for a hotel stay that the presenter provided for an engagement. Most presenters that I work with pay for the hotels, but never once has the value of that hotel been included on the 1099 that the artist was sent. This particular place is a big resort, they too are the presenter. They often trade rooms for fees (it’s a very exclusive resort!), or they give small fees plus the accommodations (which includes meals), usually for two nights as a perk to the artist. It gets tricky for the artist, because they don’t pay for the hotel, so they have no expense to write off for that income. So that may mean they end up paying tax on that amount, thereby losing money doing this performance. That’s where this goes wrong for the artist, in my opinion. Artists obviously do this gig because of the resort. But, this has left a bad taste. What’s up with issuing the 1099? They say it is an IRS law that says hotel costs are income for the artist. By the way, they don’t tell you this up front…Searching for the Truth Dear Searching for the Truth: The answer to your question depends on the specific facts of the situation. (A lawyer’s favorite answer to every question is – “It depends”!) Generally, if a presenter provides accommodations to an artist as part of the artist’s compensation, the value of the accommodations is NOT considered taxable income to the artist, if the accommodations are reasonable and necessary. For instance, if an artist is travelling from California to New York to play one show, the presenter providing the artist with two nights of hotel accommodations is reasonable and necessary. The value of the hotel accommodations in this instance would not be considered taxable income to the artist, and need not be included on the 1099. On the other hand, if a pianist travels away from home to play a concert and the presenter provides hotel and airfare for the pianist, her husband, her sister, her sister’s next-door neighbor, and the next-door neighbor’s pet monkey, this is not reasonable and necessary. The value of the airfares and accommodations for everyone except the pianist would be considered taxable income and SHOULD be reported to the artist on a 1099. Unfortunately for your artist, there are a few comments in your letter that indicate that the accommodations at the resort exceeded the “reasonable and necessary” standard. You state that the artists at this resort often accept accommodations in lieu of fees, or accept smaller fees plus accommodations. Why would an artist accept no fee, or a substantially smaller fee, if the artist wasn’t receiving something of value (in addition to the hotel room) in return? Plus, you mention that artists “do this gig because of the resort”… and the presenter provides “two nights as a perk to the artist”. Again, the artist is receiving something of value besides the usual hotel accommodations. If an artist is receiving a significant personal benefit from the accommodations besides a place to lay his head after the show (such as the opportunity to enjoy resort amenities or an extra night of accommodations), then the value of the accommodations constitutes taxable income and must be reported. You say that it’s tricky for the artist, because he has no expense to write off his income. But wouldn’t this be the case if he was receiving his usual fee plus a regular, non-resort, hotel room? I’d suggest that in the future, unless your artist understands the taxable “value” of receiving resort accommodations, including the included room service and use of the infinity pool, have him stay at the Motel 6 down the street. _________________________________________________________________ For additional information and resources on this and other legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com To ask your own question, write to lawanddisorder@musicalamerica.org. All questions on any topic related to legal and business issues will be welcome. However, please post only general questions or hypotheticals. GG Arts Law reserves the right to alter, edit or, amend questions to focus on specific issues or to avoid names, circumstances, or any information that could be used to identify or embarrass a specific individual or organization. All questions will be posted anonymously. __________________________________________________________________ THE OFFICIAL DISCLAIMER: THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE! The purpose of this blog is to provide general advice and guidance, not legal advice. Please consult with an attorney familiar with your specific circumstances, facts, challenges, medications, psychiatric disorders, past-lives, karmic debt, and anything else that may impact your situation before drawing any conclusions, deciding upon a course of action, sending a nasty email, filing a lawsuit, or doing anything rash!

Historical Pianists from Sony; Kronos at 40

July 18th, 2013by Sedgwick Clark

With copyrights soon to expire, several major labels are releasing huge box sets of their holdings for their Last Hurrah at ridiculously low prices. One of the first was Sony Classical’s complete Stravinsky Conducts Stravinsky series on 22 CDs for $45. Others from Sony are complete editions of Toscanini, Rubinstein, and Heifetz, with Horowitz on the way. Universal has released sets of Curzon, Ferrier, the complete operas of Wagner and Verdi, Solti’s Wagner Ring remastered, and two delicious 50-CD boxes of Mercury Living Presence with a third set reportedly in the works. Decca will celebrate the Britten centennial soon with all of the composer’s recordings in one mammoth set. And the prices are IN-SANE!

Graffman and Fleisher—Two OYAPs Complete

Sony Classical has just announced upcoming box sets of its complete recordings of Gary Graffman (on RCA and Columbia) and Leon Fleisher (Epic and Columbia), two of the pianists known in the early 1950s as OYAPs—Outstanding Young American Pianists. Others in the group included William Kapell, Julius Katchen, Eugene Istomin, Jacob Lateiner, and Claude Frank.

The 23-CD Fleisher set will be released on the pianist’s 85th birthday, July 23, and includes several famous concerto recordings with George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra: Beethoven’s 5, the two Brahms, the oft-coupled Grieg and Schumann, and Rachmaninoff’s Paganini Rhapsody. After trying out innumerable Beethoven sets over the past 40 years, I’ve given up trying—there are simply none I’ve ever heard to match the Fleisher/Szells—and the Brahms pair offers a blazing, young man’s view, especially of the turbulent First.

Graffman turns 85 on October 14 and will be fêted with a 24-CD set on September 24th. Among the treasures within will be Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto and Paganini Rhapsody with Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, Tchaikovsky’s Second and Third Concertos with Ormandy and the Philadelphians, and the famous First with Szell and Cleveland. But my favorite Graffman recording is of the First and Third Prokofiev concertos with Szell and Cleveland. I’ll never forget hearing this Third for the first time; few recordings in my collection trigger goose pimples as vividly.

Both artists, by the way, produced delightful memoirs. Fleisher collaborated with the Washington Post’s chief classical music critic, Anne Midgette, in My Nine Lives: A Memoir of Many Careers in Music (Doubleday, 2010). Graffman’s alliterative I Really Should Be Practicing: Reflections on the Pleasures and Perils of Playing the Piano in Public (Doubleday, 1982) is particularly puckish.

And now, Sony, you could give pianophiles triple pleasure by releasing the Epic and Columbia recordings made by a third American pianist from this generation, Charles Rosen, who died last December at age 85. While hailed for his lucid performances of 20th-century classics—solo works by Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Bartók, Carter, and Boulez—his recordings of works by Bach and Beethoven received equally high acclaim. Rosen was Musical America’s Instrumentalist of the Year in 2008.

Lincoln Center Hails Kronos at 40

Here’s another cringe-inducing fact of life for old-timers: the Kronos Quartet is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year. (It was disturbing enough when Kronos was on Musical America’s cover ten years ago!) So we’ll just note the fact and point out that Lincoln Center Out of Doors is putting on 28 Kronos concerts and events between July 24-28. No one who knows Kronos will be surprised that the most up-to-date accessories will be utilized in its performances, to wit a composition by Dan Deacon that “features one of his most recent crowd-participation creations: a light-show generated by audience smartphones via his downloadable app.”

Here, courtesy of DotDotDotMusic, are complete programs. Each evening of KRONOS at 40 touches on a distinct programming theme:

- The opening evening, Wednesday, July 24, is inspired by the kinetic sounds of Afrobeat music, with Superhuman Happiness and drumming legend Tony Allen, and members of Broadway’s Fela! The festivities begin with Mark Dendy’s new site-specific dance work for 80 dancers, set to classic Kronos recordings from its Nonesuch catalog.

- In the Thursday, July 25 program, indie rock meets eclectic art song with My Brightest Diamond (Shara Worden), multi-instrumentalist Emily Wells, and Ukrainian singer Mariana Sadovska.

- Diverse global sounds rule the Friday, July 26 offerings, including Greek singer/multi-instrumentalist Magda Giannikou, Irish music supergroup The Gloaming, and Vietnamese musician Vân-Ánh Vanessa Võ.

- Saturday, July 27 is family day, with kids’ music hero Dan Zanes, the Brooklyn Youth Chorus, and the gifted Pannonia Quartet from the Special Music School’s Face the Music program.

- The grand finale, Sunday, July 28, features premieres by rock experimentalists Jherek Bischoff, Dan Deacon, and Amon Tobin.

Following are further details, by date and with programs in order of artist appearance; all programs are subject to change.

And don’t forget about the companion exhibition. The New York Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, Plaza Corridor Gallery, is presenting For the Record: The World of Kronos on Nonesuch Records through August 30. The exhibition features original Kronos album cover artwork, composers’ manuscript materials, international awards, Kronos listening stations, and more. Further details at http://www.nypl.org/events/exhibitions/record-world-kronos-nonesuch-records.

Wednesday, July 24�

This concert anticipates the upcoming album release, Red Hot + Fela, organized by HIV/AID awareness and relief organization, Red Hot. The program celebrates the legacy of Fela Anikulapo Kuti, Nigerian multi-instrumentalist musician and composer, pioneer of Afrobeat music, and human rights activist.

6 pm – Mark Dendy Dance & Theater Projects Ritual Cyclical World Premiere Josie Robertson Plaza

7:30 pm – Superhuman Happiness: Music from How to Survive a Plague Damrosch Park Bandshell

Red Hot + FELA LIVE! (World premiere)

Featuring: Tony Allen and Superhuman Happiness

with Baloji, Abena Koomson, Kronos Quartet, Sahr Ngaujah, Sinkane, and Kalmia Traver

Musical Director: Stuart Bogie

Thursday, July 25�

Vocalist/composer Sadovska joins Kronos in the premiere of her work regarding the catastrophic Chernobyl nuclear plant disaster of 1986, which took place in her native Ukraine.

6 pm – Mark Dendy Dance & Theater Projects (see July 24) Josie Robertson Plaza

7:30 pm – Kronos Quartet with special guest Mariana Sadovska (voice): Chernobyl.The Harvest. US premiere Damrosch Park Bandshell

– Emily Wells Damrosch Park Bandshell

– My Brightest Diamond Damrosch Park Bandshell

Friday, July 26�

Kronos is joined by Greek composer/performer Giannikou on the laterna, a hand-cranked, portable barrel piano popular in Greece in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and Võ on traditional Vietnamese instruments, including the dan tranh zither. Found Sound Nation creates music from passers-by and environmental sounds.

4:00 pm – Found Sound Nation Josie Robertson Plaza

6 pm – Chinese American Arts Council: Romance of the Iron Bow Josie Robertson Plaza

7 pm – Magda Giannikou: traditional Greek laterna music Josie Robertson Plaza

7:30 pm – The Gloaming Damrosch Park Bandshell

– Kronos Quartet Damrosch Park Bandshell

Program to include:

Omar Souleyman (arr. Jacob Garchik): La Sidounak Sayyada (I’ll Prevent the Hunters from Hunting You)

Alter Yechiel Karniol (arr. Judith Berkson): Sim Sholom

Ramallah Underground (arr. Jacob Garchik): Tashweesh

Traditional/Kim Sinh (arr. Jacob Garchik) / Lưu thủy trường

Vân-Ánh Vanessa Võ / Selections from All Clear�

Vân-Ánh Vanessa Võ / Queen of the Night�

with special guest Vân-Ánh Vanessa Võ, dan tranh

Ram Narayan (arr. Kronos, transc. Ljova): Raga Mishra Bhairavi: Alap

Magda Giannikou / Strophe in Antistrophe World premiere �

with special guest Magda Giannikou, laterna, Keita Ogawa and Marcelo Woloski, percussion

Saturday, July 27

“Family Day”

Featuring boundary-stretching, innovative, new work being created for and performed by the next generation of young artists, including many who have collaborated with Kronos. With Latin, Hip-hop, rock, funk band Ozomatli from Los Angeles, and the group’s family-friendly offshoot, OzoKidz.

11:30 am – 2 pm / 4:30 – 7:30 pm – Found Sound Nation Josie Robertson Plaza

12 pm – 4 pm – Craig Woodson, MC Hearst Plaza

Elena Moon Park & Friends

Face the Music – Pannonia Quartet

Aleksandra Vrebalov / Pannonia Boundless

Steve Reich / Different Trains

Michael Daugherty / Sing Sing: J. Edgar Hoover

Brooklyn Youth Chorus

Play-Along Concert with Kronos

5 pm – OzoKidz Damrosch Park Bandshell

– Dan Zanes & Friends: Tribute Lead Belly Damrosch Park Bandshell

Program to include: Huddie Ledbetter / Grey Goose

8 pm – Ozomatli Damrosch Park Bandshell

Sunday, July 28�

The final concert of Kronos’s week at LCOOD features experimental pop composer/electric guitarist Bischoff, who will perform with Kronos; Deacon, who will appear with the group on live electronics, involving the audience with a smartphone app; and, from Russia, 21-year-old Juilliard Teaching Fellow Boguinia, the youngest composer to be premiered by Kronos this season. Amon Tobin’s Notoation receives its East Coast premiere on this program also. Kicking things off are Jacob Garchik’s self-proclaimed “atheist trombone shout choir” The Heavens, and new-music marching band provocateurs Asphalt Orchestra, performing their arrangement of The Pixies’ breakthrough album Surfer Rosa on the 25th anniversary of its release.

3:30 pm – 6 pm – Found Sound Nation Josie Robertson Plaza

6 pm – Parades: Asphalt Orchestra and Jacob Garchik’s The Heavens Josie Robertson Plaza

6:30 pm – Asphalt Orchestra premieres The Pixies‘ Surfer Rosa Damrosch Park Bandshell

– Jacob Garchick’s The Heavens Damrosch Park Bandshell

– Kronos Quartet Damrosch Park Bandshell

Program to include:

Bryce Dessner / Aheym (Homeward)�

Nicole Lizée / Death to Kosmische�

Clint Mansell (arr. Kronos Quartet) / Death is the Road to Awe (from The Fountain)

Amon Tobin (realized by Joseph Colombo) / V838 Monocerotis East Coast premiere

Jherek Bischoff / A Semiperfect Number World premiere

with special guest Jherek Bischoff, bass guitar

Yuri Boguinia / On the Wings of Pegasus World premiere

Clint Mansell (arr. Kronos Quartet) / Death is the Road to Awe from The Fountain

Dan Deacon / Four Phases of Conflict for string quartet, electronics, and audience World premiere

with special guest Dan Deacon, electronics

For further details visit http://www.lcoutofdoors.org. See you at Lincoln Center!

A Manager’s Deposit of Trouble

July 17th, 2013By Brian Taylor Goldstein, Esq. Dear Law and Disorder: We are a small classical music presenter. Several months ago, I booked an artist for a performance this fall. Recently, I received a phone call from the artist’s manager asking for a deposit. Usually, we don’t pay deposits, although, sometimes we will if it’s an artist or manager with whom we have never worked before. However, we’ve worked with this manager before and she’s never asked for a deposit before. When I asked her about it, she said that she (the manager) was having a slow summer and that she needed the money to give her some cash flow to “tide her over” until the fall. She threatened to cancel if I didn’t agree. Is this legal? As a general rule, I’m a big fan of deposits. They provide artists with some “leverage” in the event of a cancellation and they provide presenters with some assurance that an artist has, in fact, been “booked.” However, once all key terms have been negotiated and agreed upon, whether or not a written booking agreement has been signed, then a manager cannot retroactively “require” a deposit. The requirement of a deposit is a key term which needs to be discussed, negotiated, and agreed upon at the outset of discussions. If the artist were to cancel because you refused to pay a deposit you never agreed to pay in the first place, then the artist would be in breach of the booking agreement. But that’s not really the problem here. The problem is that the manager volunteered that she was asking for the deposit not for the benefit of the artist, but for the benefit of the manager herself. It would be different if the manager wanted the deposit to reserve airline tickets or advance costs to cover the artist’s out-of-pocket expenses. However, according to you, that’s not what the manager said. She said she wanted it to “tide her over” for the manager’s own cash flow purposes. Based on that statement, and her subsequent threat to cancel if you refused to pay the deposit, the manager’s actions are not only unethical and unprofessional, in my opinion, but, more importantly, highly illegal. Managers and agents are legally bound to act only on behalf of and in the best interest of their client (the artist) and not on behalf of themselves or anyone else. In legal terms, these obligations are called “fiduciary duties.” Managers and agents can take no actions which are not authorized by the artist and most certainly cannot treat the artist’s money as if it were their own—including asking for and using deposits to float themselves loans to cover their own cash flow needs. This is why, among other reasons, managers and agents are supposed to keep their own, personal operating accounts separate from their client’s (artist’s) accounts. This should not be confused with legitimate situations where managers and agents sometimes ask presenters to split an engagement fee into two payments and pay a commission fee directly to the manager or agent and the balance to the artist. While I find this to be an ill-advised and awkward business practice, it’s neither illegal nor unethical. While I suppose its entirely possible that, in this case, the manager was acting with her artist’s knowledge and authority, I seriously doubt it. This means that the manager was acting out of her own self-interest and not in the best interest of her artist, is in breach of her fiduciary duties, is no longer acting in her legal capacity as a representative of the artist, and, in the event of a cancellation, would be personally liable for the return of the deposit and any damages. Given the manager’s self-admitted cash flow problems, that’s probably a risk you don’t want to take. I’d like to think that the manager is acting out of a genuine confusion over the duties agents and managers owe to their artists. Sadly, this issue continues to confuse even experienced managers and agents who believe that their artists work for them and not the other way around. Regardless, in terms of red flags, this one is ten feet tall and on fire. Run away! __________________________________________________________________ For additional information and resources on this and other legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com To ask your own question, write to lawanddisorder@musicalamerica.org. All questions on any topic related to legal and business issues will be welcome. However, please post only general questions or hypotheticals. GG Arts Law reserves the right to alter, edit or, amend questions to focus on specific issues or to avoid names, circumstances, or any information that could be used to identify or embarrass a specific individual or organization. All questions will be posted anonymously. __________________________________________________________________ THE OFFICIAL DISCLAIMER: THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE! The purpose of this blog is to provide general advice and guidance, not legal advice. Please consult with an attorney familiar with your specific circumstances, facts, challenges, medications, psychiatric disorders, past-lives, karmic debt, and anything else that may impact your situation before drawing any conclusions, deciding upon a course of action, sending a nasty email, filing a lawsuit, or doing anything rash!

Liederabend with Breslik

July 9th, 2013

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: July 9, 2013

MUNICH — With the brightness of his voice working against him at every turn, Pavol Breslik blazed and sweated his way through Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin last Friday (July 5) here at the Prinz-Regenten-Theater. By the end, drowned in Wilhelm Müller’s creek, he had somehow won over the packed house.

Tension built up often disagreeably. Six or seven of the twenty songs were rushed. Breaks for bottled water upheld a stagey tautness, and yes, nervousness. But in reflective settings, once the voice had warmed up, the neatly groomed lyric tenor found beauty and tonal variety. Des Müllers Blumen and Tränenregen, already at the cycle’s mid-point, introduced the first degrees of poignancy and due expression. Not until Der Müller und der Bach and the concluding lullaby, however, did Breslik imaginatively tap the tension instead of adding more, leading to rapt applause.

Born in Slovakia in 1979, with early training at the Academy of Arts in Banská Bystrica, this artist delivers a smooth Belmonte or ardent Lensky on other nights. He can immerse himself in a long musical line and endow it with supple legato phrasing. On this night he took no artistic shortcuts, betrayed no mannerisms, and seemed genuinely lost in the moment during much of the cycle. His sung German sounded fluent; he is clearly passionate about the words he sings. Only when he spoke (about bottled water) was an accent discernible.

Amir Katz, born in 1973 in Ramat Gan, Israel, provided cagey, fleet support, which seemed a reasonable approach — perhaps the only approach — given Breslik’s avid absorption.

Photo © Neda Navee

Related posts:

MPhil Bosses Want Continuity

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

Liederabend with Hvorostovsky

Volodos the German Romantic

Verdi’s Lady Netrebko

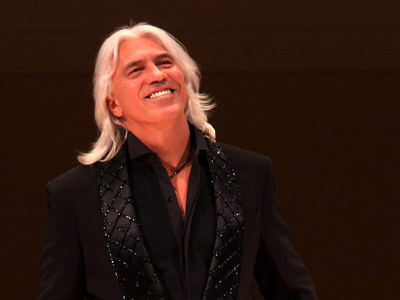

Liederabend with Hvorostovsky

July 9th, 2013

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: July 9, 2013

MUNICH — For years now Dmitri Hvorostovsky has been including in his recitals the same handfuls of songs by Sergei Taneyev and Nikolai Medtner. Colorful, intimately dramatic, and flattering to the baritone’s voice, they do not comprise cycles or alas make satisfying groupings — Hvorostovsky has shown more devotion to the music of Georgy Sviridov, performing integral works such as the Six Pushkin Romances of 1935 and the song cycle Petersburg of 1995 — but here they were again on Wednesday (July 3), five settings from each composer and all dating from 1903 to 1915, for a sold-out Prinz-Regenten-Theater.

Taneyev’s conversational Менуэт (Minuet), Op. 26/9, found the charismatic Siberian at his most engaging and natural, the voice relaxed and velvety. The somewhat clamorous Зимний путь (Winter Road), Op. 32/4, emerged free of strain. Medtner’s generally more ardent scores stretch the vocal line in awkward ways and require a few sustained tenor flights, but none of this seemed to phase Hvorostovsky, who rose robustly to the selected challenges. Long-held endings to Medtner’s unrelated Goethe settings Счастливое плаванье (Glückliche Fahrt), Op. 15/8, and Ночная песнь странника (Wandrers Nachtlied), Op. 6/1, wowed the crowd. Indeed, Hvorostovsky condoned applause after every song and seemed unfazed by flash photography. Ah, showmanship.

Ivari Ilja, a tall man of Churchillian gaze, matched the singing with audacious accompaniment. Still, his way with the relatively tranquil Ночная песнь странника left a congenial mark, and balances between the two artists proved ideal. Liszt’s Tre sonetti del Petrarca and disparate Rachmaninoff songs were slated for the second half of this recital. We ran for the train.

Photo © BBC

Related posts:

See-Through Lulu

Liederabend with Breslik

Verdi’s Lady Netrebko

Written On Skin, at Length

Kaufmann, Wife Separate

Bob Fosse’s Lasting Legacy?

July 7th, 2013By Rachel Straus

To many, Bob Fosse’s style, with its pelvic thrust, razzle-dazzle hands, and slumped over set of shoulders, is immediately recognizable. Fosse championed the vaudevillian delinquent, the burlesque maven, the professional huckster. He bucked the post World War II musical theater tradition of happy boys and girls and their dancing feet. Yet despite Fosse’s unquestionable influence on musical theater dance, his most important contribution may be his film work. Fosse rejected the tradition, best exemplified by the dance numbers in Fred Astaire films, of capturing the dancing figure from head to toe. Press on the link below to see Astaire dancing and singing to Irving Berlin’s tune “No Strings (I’m Fancy Free)”; the camera is more or less stationary, and the dancing section of this scene looks like it was shot in one take: Astaire in Top Hat (1935)

In contrast to Astaire, Fosse dispensed with the notion that a good dance sequence had to be continuously shot, that dancers had to project bodily ease, and that the viewer was a good samaritan ready for some light entertainment. In Sweet Charity (1969) Fosse’s dancers appear as burlesque matrons. They barely move, and when they do, they look like zombies trying to be sexy. Through his directorial and choreographic choices in the film, Fosse makes the viewer complicit in the vulgarity of The Big Spender number. He shoots, in fast whiplash cuts, the dancers’ bodies from the perspective of one male customer, sitting in the front row and smoking a cigarette. By shooting their body parts in isolated shots, Fosse aggressively tenders the idea that these gals are broken. Bust and flanks, bones and flesh, brimstone and fire. That’s what Fosse captures. Take a look: Big Spender number in Sweet Charity (1969) No doubt, the Big Spender number is a brilliant conceived use of film and dance.

So what’s Fosse’s ultimate legacy? For my money it’s Fosse’s mature dance-film style, seen in the Big Spender number. Too many people have imitated it. His gestural-driven (and sleaze-riddled) dance numbers are completed by the camera’s close-ups and the subsequent multiple edits, which give one the sense of a hungry eye, roving from one dancer to the next. This pasting and cutting approach to filmed choreography became, after Fosse, the defacto tradition for mass media dance film. It can be seen in Michael Jackson dance videos, the famous Maniac (1983) dance number from Flash Dance, and in Maddona’s Vogue (1990). In each case, the choreography takes second place to the ingenious, energetic filming and editing. Jackson’s music video Bad may be the pinnacle of the Fosse dance-film style. The performers are shot from below (as though one is begging the gang members for mercy—underneath their very chins). The dancers’ pelvic thrust isn’t insouciant, as in the case of Fosse dancers, but outright aggressive. Jackson and his crew’s gestures are mechanical. The zombies have become machines.

Michael Jackson’s Music Video Bad (1987) In the next posting, I’ll explore how mass media dance, like So You Think You Can Dance and Bunheads, may not be doing much for the art of choreography, but they have shed the Fosse dance-film style. The powers that be have actually returned to the tradition of shooting the full dancing body instead of parts of it. What is conveyed, however, is not a integrated moving figure, but something quite different.

Stravinsky Stuff

July 4th, 2013by Sedgwick Clark

The 2012-13 season began at New York City Ballet with a three-program mini-festival of Stravinsky-Balanchine works. It ended last week with Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic in a “theatrical reimagining” at Avery Fisher Hall of Stravinsky’s Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss) and Petrushka. May 29 was the 100th anniversary of the scandalous first performance of Le Sacre du printemps. I took on listening to 49 recordings in a pair of historical collections from Decca and Sony Classical. That took longer than the week I had anticipated, domestic matters and other deadlines being what they are, but the results of my listening sessions—with my new comments in blue—are finally posted in toto below.

Alan Gilbert’s Stravinsky—A Dancer’s Nightmare

In each of his four seasons so far, New York Philharmonic Music Director Alan Gilbert has ended with a Major Project. First, Ligeti’s opera Le Grand Macabre, then Janáček’s opera The Cunning Little Vixen, and last season a program of works for multiple orchestras at the Park Avenue Armory: Stockhausen’s Gruppen, Boulez’s Rituel, an excerpt from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, and Ives’s The Unanswered Question. All daring, to say the least, and all smashing successes with the public and critics.

Everyone’s doing Stravinsky this year due to the centennial of Le Sacre, so Gilbert coupled two ballets for his fourth extravaganza: the rarely performed Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss) from 1928 and the enormously popular Petrushka (1911).

First, the good part. The musical portion of the program was first-rate. The Philharmonic musicians played beautifully, and Gilbert was at his best. He’s not a ballet conductor, and Baiser’s opening minutes meandered a bit, lacking point and accent. But the music quickly assumed its idiomatic Stravinskian rhythmic profile, and the ending, which in lesser hands can seem overlong, was quite lovely. Le Baiser is Stravinsky’s homage to Tchaikovsky, utilizing many of his lesser-known melodies (mainly piano works). A moment from the Fifth Symphony flashes by, but the only truly familiar piece borrowed for any length of time is Tchaikovsky’s song None but the lonely heart as the climax of the work. As for Petrushka, Gilbert elicited a magnificent performance. But the dance and staging portion of the evening was a perfect example to those who believe that orchestras should stick to orchestral music, for which they were created. Hard on the heels of Gilbert’s distinguished, straightforward concert presentation of Luigi Dallipiccola’s opera Il Prigioniero (6/6), this Stravinsky program, marketed as “A Dancer’s Dream,” was embarrassingly cutesy.

As I’ve admitted before, I’m not knowledgeable about the ballet; I go primarily when the music interests me. But the choreography, by Karole Armitage, struck me (and several others who are balletomanes) as amateurish and the use of New York City Ballet Principal Dancer Sara Mearns as a colossal waste of talent. I was astounded to read Alastair Macaulay in the Times: “The choreography, by Karole Armitage, could only have a limited effect in conditions so cramped, but individual phrases very much along Balanchine lines, beamed out powerfully.”

49 Recordings of Le Sacre du printemps – Finished at Last!

It may seem unnecessary to audition and report on 49 recordings of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps (The Rite of Spring) since 38 of them can be obtained only in a single set from Decca and another 10 from the Columbia and RCA catalogues in a set from Sony Classical. But if fellow Stravinskyites relish my Sacre orgy, they might be persuaded to acquire these sets too and have an equally pleasurable wallow. In a day when any professional orchestra can whiz through the piece without blinking, it’s fascinating to hear the oldest recordings and realize how daunting Le Sacre once was.

My preferred recordings in these sets are listed below, in order of preference.

Clark’s Top 6

• Columbia Symphony/Igor Stravinsky (1960; 31:35). Sony

• Boston Symphony/Pierre Monteux (1951; 31:25). Sony

• Cleveland Orchestra/Pierre Boulez (1969; 34:34). Sony

• Boston Symphony/Michael Tilson Thomas (1972; 34:00). Decca

• Chicago Symphony/Georg Solti (1974; 32:12). Decca

• Berliner Philharmoniker/Bernard Haitink (1995; 32:48). Philips

Sony Classical’s Centenary Releases of The Rite of Spring

Igor Stravinsky – Le Sacre du Printemps – 100th Anniversary Collection – 10 Reference Recordings

CD 1

Philadelphia Orchestra/Leopold Stokowski (1929/1930). Shocking! In our day of recorded perfection, it’s difficult to say which of Le Sacre’s first three recordings, is the worst played: Monteux, Stravinsky, or this Stokowski, all recorded within a year of each other. RCA’s 78s are more vivid sonically than this CD or any LP transfer I’ve heard—enough so that a recent spot check revealed the kind of sensuous details that separated him from nearly every conductor of the 20th century, and which I never noticed before. I’m glad Sony included it, but non-collectors may find listening a chore. (32:39)

CD 2

New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra/Igor Stravinsky (1940). A very tight reading. One wishes he would relax a little and invest the music with more expressiveness at times, but the New Yorkers do well by the score, with only occasional imprecision, until they stumble over the rhythmic complexity of the concluding Danse sacrale. Still, it’s a huge improvement over his 1929 Paris recording. The 78s have notably more presence and tonal warmth. The recording date, by the way, is April 29, 1940, not April 4, as the back of the package states. (30:45)

CD 3

Boston Symphony/Pierre Monteux (1951). Monteux conducted the infamous first performance of Le Sacre. He made four recordings, and this is far and away his best. The BSO players seem to be playing on the edge of their seats with commitment, and a few scrappy moments—most in the Danse sacrale—hardly detract from this great, well-recorded performance. (31:35)

CD 4

Philadelphia Orchestra/Eugene Ormandy (1955). Ormandy reportedly maintained that he never conducted Le Sacre. It certainly isn’t his piece. Timpani are muffled throughout, and woodwind details are often obscured by Philly’s glamorous strings. This is its first release on CD, sounding rather dim from what I take to be its LP work tape rather than the master source. Too bad Sony didn’t include Ormandy’s Petrushka Suite from the LP, which is more his style. (29:49)

CD 5

Columbia Symphony/Igor Stravinsky (1960). The composer’s stereo recording of Le Sacre (as well as his 1940 mono recording with the New York Philharmonic-Symphony, which is only 50 seconds shorter) has unrivalled rhythmic accentuation, clarity, and balletic character. There are more exciting, splashily recorded versions, but this performance simply feels “right.” (31:35)

CD 6

Chicago Symphony/Seiji Ozawa (1968). I was at Ravinia, the CSO’s summer home, for the concert preceding the recording session. It was exciting then and it is now, even if the performance style is somewhat generalized. But it’s superbly played, and a sad reminder of the promise Ozawa had that was never quite fulfilled. He tightens the pace at the end as Monteux did, no less effectively. (32:46) Fireworks from the original LP is included first, as before.

CD 7

Cleveland Orchestra/Pierre Boulez (1969). The French conductor’s 1963 Paris recording was fast, fiery, and on its toes. But he came to feel, he said to me in an interview, that such febrile tempos trivialized the work. This Cleveland performance can seem a bit earthbound at times, but following the score reveals all sorts of details that other conductors gloss over and that Boulez reveals without calling attention to them, such as the three accented trumpet notes on page 31 that so many treat indifferently (but not Ormandy!). The players are at their best, and the recording is the utmost in clarity. (34:34)

CD 8

London Symphony/Leonard Bernstein (1972). The best thing about this Sacre is the faux Rousseau, pop art cover. It’s a surprisingly tepid Sacre from this most un-tepid conductor. Originally recorded for quad by producer John McClure, the wet acoustic obscures much detail. (35:29)

CD 9

Philharmonia Orchestra/Esa-Pekka Salonen (1989). Hopelessly flashy. The slow tempos are very slow, and the fast ones very fast in this absurdly bifurcated Sacre. It’s very exciting but counterproductive to any musical continuity and impossible to dance to. His later DG recording is more traditionally paced. (32:13) A fine Symphony in Three Movements is included from the original CD release.

CD 10

San Francisco Symphony/Michael Tilson Thomas (1996). MTT remains a master of Le Sacre with all the details so often missing in other performances right in place, superbly played and recorded. The Glorification and Evocation sections may seem a bit hasty, but they stir the blood. (34:54)

Stravinsky conducts Le Sacre du Printemps

CD 1

Le Sacre du Printemps (1960). See CD5 above.

Firebird Ballet Suite (revised 1945 version). Columbia Symphony Orchestra/Igor Stravinsky (1967). Stravinsky’s most popular and frequently performed piece is the 1919 Suite from The Firebird ballet. But it was not under copyright and he never made a dime from it. So in 1945 he arranged and reorchestrated a new suite, adding several dances from the complete ballet. Most orchestras continued to perform the 1919 suite, however, because they didn’t have to pay royalties for it. I listened to this “bonus” stereo recording directly after hearing his 1946 recording. What a difference in the expressiveness of his conducting; the music breathes with rubato, affection, and breadth, especially in the horn solo and strings of the Final Hymn, before the brass fanfare of Palace Merrymaking. It’s as if he knew it would be his final recording. And indeed it was. (29:24)

CD 2

Le Sacre du Printemps (1940). See CD2 above.

Firebird Ballet Suite (revised 1945 version). New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra/Igor Stravinsky (1946). This new suite was hot off the presses when Stravinsky recorded it. But some transitions were abrupt—especially jarring between the Berceuse and Final Hymn—and before the score was printed he added three Pantomimes and brief transitional material, totaling about three minutes. It’s good that Sony decided to include these two Firebird suites and allow us to hear a great composer at work. (26:00)

Decca’s Complete Collector’s Edition: Le Sacre du printemps

CD 1

Concertgebouw Orchestra/Eduard van Beinum (1946). The oldest Sacre in this set, it is remarkably well played and conducted. Tempos are similar to the composer’s. It lacks the detail of modern recordings, of course, but it’s full of atmosphere. Timpani mostly inaudible. Fine transfer, with no audible 78 joins. (32:08)

L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande/Ernest Ansermet (1950). Ansermet was one of Stravinsky’s great early champions, but his recordings are mere curios today. The insufficiencies of his Suisse Romande are all too clear, as are his devitalized interpretations. His 1957 stereo remake is no improvement. (33:56)

CD 2

RIAS Symphonie-Orchester Berlin/Ferenc Fricsay (1954). At last a recording of Le Sacre in which the timpani make their proper effect (even if the bass drum is weak)! An excellent performance, if perhaps bit too sane. (33:39)

Minneapolis Symphony/Antal Dorati (1954). A CD first. A driving, dynamic performance with all the crucial instrumental details powerfully captured in their correct acoustical space by Mercury Living Presence’s single mic. The Dance of the Earth and Danse sacrale are incredibly exciting, and the timpanist is on fire. The 1959 stereo remake is faster, seeming frantic and lightweight. (31:18)

CD 3

Orchestre des cento soli/Rudolf Albert (1956). The sleeper of the set. Decca couldn’t even find a photo of Albert! Well paced and played, it only flags a bit in the last pages of the Danse sacrale, as one imagines the exhausted virgin dancing herself to death would. The few instances of imprecise ensemble are of no concern. The German-born Albert was a contemporary-music exponent, and a few weeks after leading this recording he conducted the world premiere of Messiaen’s Oiseaux exotiques. (33:37)

Paris Conservatoire Orchestra/Pierre Monteux (1956). There are several pirate Monteux Sacres on the market, but this was his fourth and final studio recording and the only one in stereo, produced by John Culshaw. On paper it looks promising and authentic (French maestro who conducted the work’s first performance, French orchestra, recorded in Paris’s Salle Wagram), but the fact that it was recorded over a nine-day period may indicate that there were extra-musical reasons for the lackluster leadership and lax ensemble. The 1951 Boston on Sony is best. (32:57)

CD 4

L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande/Ernest Ansermet (1957). (33:52) See CD1.

Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra/Antal Dorati (1959). (29:56) See CD2.

CD 5

Berliner Philharmoniker/Herbert von Karajan (1963). Stravinsky criticized this performance as “a pet savage rather than a real one . . . . There are simply no regions for soul-searching in The Rite of Spring. Berlin’s “sostenuto style is a principal fault,” he continues. “The music is alien to the culture of its performers.” It’s a fascinating performance, with many instrumental felicities, but it’s ultimately a curio, which goes for its 1977 remake as well. (33:48)

London Symphony/Colin Davis (1963). A young man’s Sacre—exciting, athletic, well played for its time. Well recorded. (30:29)

CD 6

Los Angeles Philharmonic/Zubin Mehta (1969). The first “modern” recording from these labels, with obvious multi-miking, deep bass drum, and exaggerated timpani, as if you were onstage. The Danse sacrale is exciting and well played, which characterizes the entire performance. It may not be your ideal seat in the concert hall, but “Wow!” (32:54)

Boston Symphony/Michael Tilson Thomas (1972). Excellent playing and conducting, recorded naturally in Symphony Hall’s gorgeous ambient warmth. If occasional detail is lost, the aura of a genuine concert makes up for it. Tilson Thomas told me soon after the sessions that this was the only recording, including the composer’s own, that followed the metronome marks precisely. Whatever the case, it remains one of the best. (34:00)

CD 7

London Philharmonic/Bernard Haitink (1973). The low-level volume is not all that needs a boost, despite careful instrumental balances. (34:07)

London Philharmonic/Erich Leinsdorf 1974). Stolidly conducted, with distracting Phase 4 balances. I wonder if Leinsdorf was standing in for another maestro taken ill, as I enjoyed his sumptuous Sacre with the Boston Symphony in fall 1968 at Lincoln Center. (33:26)

CD 8

Vienna Philharmonic/Lorin Maazel (1974). This version was panned for unidiomatic playing by the VPO and Maazel’s eccentricities, but over headphones the playing is mostly accurate and quite beautiful–perhaps not what one wants in a Sacre, but interesting nonetheless. Then there are those 11 fortissimo chords that lead into the Glorification of the Chosen One section, which Maazel has the Viennese play ludicrously slow and meaty, and several other yucky protractions of brass glissandi. Of interest to the curious. His New York Phil performance during his tenure was thankfully less vulgarized. (33:41)

Chicago Symphony/Georg Solti (1974). Superbly played, no eccentricities, closely recorded. Minor imprecisions in the Glorification section prove that the musicians are human, but no matter. This is a mind-blowing Sacre, truly virtuoso, highly recommended. (32:12)

CD 9

London Symphony/Claudio Abbado (1975). A fine performance, powerfully recorded, with plenty of excellent details from the LSO, such as a fast, sinister bass clarinet before the Danse sacrale. But as usual with Abbado, I don’t hear much character in the playing to complement the precision—certainly nothing approaching Solti/Chicago. (33:17)

Concertgebouw Orchestra/Colin Davis (1976). Unlike Davis’s fiery, if not always precise, LSO recording of 13 years before, the plush CGO sonority and reverberant hall cover detail, and the conducting is overly gentlemanly. Very beautiful if that’s what you want. A tape-editing error on LP repeated the four bars after number 192 in the Danse sacrale, but the CD is correct. (34:47)

CD 10

Berliner Philharmoniker/Herbert von Karajan (1977). (34:18) See CD5.

National Youth Orchestra/Simon Rattle (1978). The most memorable live performance of Le Sacre I ever heard was Boulez leading the 145-player National Youth Orchestra of Britain in London in spring 1977. Also on the program was Bartók’s MUSPAC, with 16 double basses and an equal complement of the other strings, and Berg’s Violin Concerto with Itzhak Perlman. Boulez was in ecstasy afterwards, for good reason. Rattle’s is a capable performance marred by a stodgy Glorification of the Chosen One and Danse sacrale. (33:33)

CD 11

Boston Symphony/Seiji Ozawa (1979). His lack of exaggeration is welcome. For instance, he resists the crass distention of the brass glissandi toward the end of Spring Rounds (number 53) that most conductors indulge in. Also positive are the BSO’s excellent playing and the ideally resonant Symphony Hall acoustics. But the vicious attacks in Part 2 are too well-upholstered, and the Danse sacrale flows too smoothly, too predictably, too much like Karajan’s pet savagery. (32:37)

Detroit Symphony/Antal Dorati (1981). The first digital recording in this set. The bass drum will blow you out of the room, and it’s clearly differentiated from the timpani. But it’s rather tired—as much an old man’s performance as his 1953 Mercury one was palpably a young man’s. (33:31)

CD 12

Israel Philharmonic/Leonard Bernstein (1982). No room for soul-searching, Lenny. Stick with the Royal Edition CD of the 1958 New York Philharmonic recording. (36:57)

Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal/Charles Dutoit (1984). Warm, glowing sonics, with plenty of space around the instruments. I wish he hadn’t emphasized the brass glissandi at number 53, but there are worse. (35:08)

CD 13

The Cleveland Orchestra/Riccardo Chailly (1985). Less soft-edged than than most of his Stravinsky recordings, and there is certainly no reticence from the battery, but it’s a superficial performance overall. (32:34)

The Cleveland Orchestra/Pierre Boulez (1991). Boulez’s third outing, recorded in the resonant Masonic Auditorium, has a more distant concert-hall balance in the DG tradition. Many details are less clear than on his 1969 Cleveland recording in the Sony box above—some shockingly so, such as the inaudible forte solo horn soon after the Dance of the Earth begins, specifically notated in the score and absolutely clear in the drier Severence Hall acoustic. Timpani, too, are not always as clear on DG in the Danse sacrale. But some may prefer this less detailed Sacre, for it is marginally more expressive and never seems studied, as the 1969 recording does on occasion. (33:15)

CD 14

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Georg Solti (1991). Solti nails many details that other conductors either exaggerate or overlook, but the overall impression of this live recording is less than the sum of its parts. Occasional scrappy moments mar the generally fine ensemble, and the sound is a bit pallid. Moreover, the Danse sacrale plods, with no rhythmic lift. In concert, without competition from such superior versions as Solti’s own Chicago recording, this might not seem so bothersome. (33:55)

The MET Orchestra/James Levine (1992). A brutish Le Sacre. Many percussion details are clear at last, but then the timpani and trombones at the beginning of Ritual of the Rival Tribes are (like several others) not quite together. The Dance of the Earth’s buildup gains in volume but not excitement; compare it with the 1953 Dorati and 1951 Monteux who increase the tempo and raise you off your seat. Likewise, the Danse sacrale is just noisy and percussive.

CD 15

Deutsches Sinfonie-Orchester, Berlin/Vladimir Ashkenazy (1994). Very quiet introduction. Fine timpani playing. But in Part 2, Glorification of the Chosen One is surprisingly tame. Ritual Action of the Ancestors is admirably steady, and the bass clarinet before the Danse sacrale is frightening. But the Danse itself is dogged rather than relentless; there’s no build and terror. Still, it’s worth a listen. (34:29)

Orchestre de Paris/Semyon Bychkov (1995). Unexceptionable, with good details here and there, but nothing to compel relistening. (32:29)

CD 16

Berliner Philharmoniker/Bernard Haitink (1995). The Dutch conductor’s second Sacre is, again, by the letter of the score. But this time he has at hand the peerless Berliners instead of the workmanlike London Philharmonic (see CD7), and all sorts of details reveal themselves by sheer dint of individual instrumental virtuosity and eloquence. Producer Volker Straus seems, as well, to be more liberal with spot mics than 22 years ago, when Philips’s recording philosophy was more a photograph than a sonic creation in itself. This is a superior rendering of what Stravinsky composed. (32:48)

Kirov Orchestra, St. Petersburg/Valery Gergiev (1999). This is touted as a uniquely Russian interpretation in some circles, but I wonder if it’s just uniquely Gergiev, with the usual not-quite-precise Mariinsky playing. It’s certainly quite unlike the composer’s transparent textures and crisp accentuation. The introduction is slow and expressive. The young girls heavily stamp the Augurs of Spring, and the Spring Rounds are ponderous, with grossly exaggerated trombone glissandi. (I wonder if he had Fantasia’s dinosaurs in mind.) The Dance of the Earth is exciting but thick-textured, and Gergiev oddly appears to pull up slightly on the last note. In Part 2, moderate tempos in the Evocation and Ritual Action of the Ancestors and the Danse sacrale are very effective. The timpani playing is unlike any other performance I’ve heard, alternating between loud thwacks and inaudibility, and the final two chords are played after a very long pause. (34:35)

CD 17

Los Angeles Philharmonic/Esa-Pekka Salonen (2006). Unlike his 1989 Sony recording, tempos are traditional. Still, there’s nearly always something in a Salonen performance that pulls me up short and makes me think, “Why the hell did he do that?” At the end of Part 1’s Dance of the Earth he has the horns hold their note longer than the cutoff of the rest of the orchestra. It was all I could do to force myself to listen to the rest of the recording. (32:59)

Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France/Myung-Whun Chung (2007). A fine performance, often exciting, but unexceptionable, without challenging my favorites.

CD 18

Simón Bolívar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela/Gustavo Dudamel (2010). Not only a young conductor’s performance: The engagement of every last Venezuelan instrumentalist is palpable in every note. It may not be the ideal Sacre: For that, get an old man’s performance, the composer’s recording.

Four hands: Bracha Eden, Alexander Tamir (1968). Not bad overall, but there’s little personality to the reading, and of course Le Sacre for four hands—even as transcribed by the composer—is but a study. (34:05)

CD 19

Four hands: Güher and Süher Pekinel (1983). As faceless as Eden and Tamir are, the Pekinel twins are personality personified. But it’s an alien personality, with expressive shading, prim rhythms, and lightweight tone that emphatically do not belong in this piece. (33:22)

Four hands: Vladimir Ashkenazy, Andrei Gavrilov (1990). Of these three four-hand piano transcriptions, this is the one that sounds like a genuine interpretation of the piece, with tempos and textures that one who knows the orchestral version would recognize. Its only drawback is the Danse sacrale, which is played so fast that it seems insubstantial. (33:34)

CD 20 – Bonus CD

Violin Concerto

Samuel Dushkin violin, Lamoureux Concert Orchestra/Igor Stravinsky (1935). To no surprise, Stravinsky’s first recording of his Violin Concerto has the same interpretive parameters as his 1961 recording with Isaac Stern. Also, to no surprise, Stern plays the slow movement with more juice. Both recordings are welcome. (20:59)

Kaufmann Sings Manrico

June 28th, 2013

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: June 28, 2013

MUNICH — It helps when two of Caruso’s “four greatest singers” live nearby, the more so when they act as capably as they sing. That was the edge enjoyed by Bavarian State Opera in restaging Verdi’s Il trovatore to open its 138-year-old Munich Opera Festival yesterday, one of no fewer than 17 operas by Verdi and Wagner to be given here in the next 35 days. But leave it to Nikolaus Bachler — gifted narrator, sometime actor, and guiding light at this, Germany’s richest and busiest opera company — to OK a staging scheme that substitutes Age of Steam vaudeville and farce for 15th-century Aragón and Vascongadas melodrama, black-on-black sets and glaring white-neon slashes for Latin color, rootless stand-ins for impassioned characters.

French régisseur Olivier Py “focuses on the darkness, nightmare and horror of the story,” making use of a rotating four-level unit set, with add-ons and modular subtractions as events unfold. Engaging for a while, the unit unavoidably out-twirls its welcome and by Parts III and IV, bereft of sufficient new dramaturgical thought, it is largely shunted aside. Sooner than that, however, Py’s translocation trivializes the tale. Ferrando’s story-setting — the sleeping babies, the gypsy hag and all — plays on a vaudeville stage-within-the-stage to men in suits and ties. After an Anvil Chorus sparked by hammerings on a steam locomotive, all depart, leaving Azucena to wail her own backgrounder (Stride la vampa!) with no audience. Leonora’s rescue from a convent future misfires as a result of action split onto two non-competing levels, and Manrico’s execution confounds all situational logic. Ah well, at least there is Azucena’s nude mom-ghost as constant company.

Those locals, Anja Harteros* and Jonas Kaufmann, made their scenic role debuts amid this nonsense. It was her night, not so much the troubadour’s, but both sang with consistent beauty of tone and expressive point. Aided by conductor Paolo Carignani, the Greek-German soprano delivered a luxuriant, pleasingly inflected Tacea la notte placida and later fairly milked D’amor sull’ali rosee, bringing down the house. Then Carignani, otherwise robust of purpose, failed to inject tension for the Miserere and Leonora’s ensuing stretta fell flat. Kaufmann traversed his seventh Verdi role with power to spare. Ah sì, ben mio, sung against a reflecting board, drew best use of his bronzed timbre and deft messa di voce. On the phrase O teco almeno he mustered (to these ears**) a high B‑flat and held it without strain for four seconds. He refused to push for volume in the All’armi! — a smart Manrico, no mad thriller.

Caruso’s quartet found completion in relative veterans Elena Manistina and Alexey Markov, an Azucena and Conte di Luna pairing at the Met this past January. She unquestionably has the chops for the gypsy — contralto with an extended top, more than mezzo-soprano as marketed — but she did not yesterday convey terror, horror or motherhood. After an impeccable Il balen del suo sorriso, Markov’s unified, rich baritone seemed to fade. He came nowhere near to matching Harteros in the sexually charged sequence Mira, di acerbe lagrime … Vivrà! contende il giubilo, the evening’s one serious musical setback. Years of Bayreuth duty have sadly lodged a beat in Kwangchul Youn’s warm and solidly trained bass. Still, as Ferrando on that vaudeville stage, he gamely and vividly introduced the story (Di due figli vivea padre beato) to Py’s implausible audience.

Carignani lifted Verdi’s lines and mostly kept the rhythms alive and taut. He favored light textures, kindly supporting the voices but depriving the string sound of bottom and resonance. The Bavarian State Orchestra played well for him; the chorus sang in unclear Italian with fair discipline. During intermission, Manistina and Kaufmann silently indulged the director in an onstage magic-trick box-sawing of the tenor’s body. Fortuitously, maybe, this passed with little notice, as the well-dressed premiere throngs were still out sipping wine, munching canapés and spooning Rote Grütze mit Vanillesoße.

[*Munich is artistic home for the soprano. She lives in Bergneustadt.]

[**For Associated Press, Mike Silverman reports a B-natural in his interview-cum-review. Annika Täuschel, reporting for BR Klassik, claims Kaufmann actually sang a high C yesterday: “Er singt es, das hohe C!”]

Still image from video © Bayerische Staatsoper

Related posts:

Safety First at Bayreuth

Manon, Let’s Go

Boccanegra via Tcherniakov

Time for Schwetzingen

Busy Week