By Rebecca Schmid

„Kinder, schaff Neues,“ (Children, create something new) Wagner wrote in an adage frequently quoted by stage directors in Germany. In Bayreuth, 136 years after the founding of his festival, the spirit is alive and well. Provocatively-minded Regietheater, for lack of a better blanket term, has come to stamp the recently installed administration on the Green Hill, which despite widespread criticism to the contrary sees itself as simply carrying on a long-standing tradition. “The artistic point of view is not much different,” said Co-Intendant Katharina Wagner in interview with reference to the previous administration under her father, Wolfgang. “It´s the continuity of the festival and just trying to get interesting interpretations here. That´s also what our father did and tried to do. But of course if you see the Chéreau Ring now, it´s not as strong as it was, and that´s the point.” She went on to compare its power to that of last year´s new Tannhäuser in a contemporary context.

Sebastian Baumgarten´s staging certainly reaffirms the notion of Bayreuth as a Werkstatt, a place where new ideas can be test-driven to give operatic works fresh relevance. The stage director attempts to transcend the dichotomy between the divine Venusberg and the mortal realm of the Wartburg by confining the action to an industrial plant that is meant to represent a self-contained community founded on ecological awareness, indirectly echoing Wagner´s Artwork of the Future in which he envisioned a society liberated from capitalist values where the Gesamtkunstwerk could thrive. Probing as the concept may be, it has no direct connection to the opera at hand, nor does an installation by Dutch artist Josep van Lieshout that doubles as a set design have any aesthetic or philosophical value. In what may be intended as a humoristic touch, alcohol abounds but is recycled daily in an “Alkoholator,” while a biogas tank will ultimately become Elisabeth´s death chamber (something which did not go down well in the German press last year given the notorious sensitivity to such direct World War Two references). A pregnant Venus cavorts freely onstage, at one point dancing with Wolfram von Eschenbach, after her mountain—caged in metal bars—descends into the basement. The audience members sitting on the sides of the stage in Brechtian fashion did little to compensate for the lack of dramaturgical arc.

Program notes by Edward. A Bortnichak argue that Baumgarten integrates Wagner´s “criticism of the natural sciences, technology and medical research of the 19th century,” an over-intellectualized idea which, even if it made itself at all apparent, would do nothing to tell the story of Tannhäuser´s renunciation of the pleasures of the flesh for redemptive love in Elisabeth. The production effectively creates total ambiguity when the goddess gives birth to what is presumably the title character´s baby at the end of the opera. Sperm-like amoebas also crawl around intermittently, but most tasteless is video art by Christopher Kondek. The x-rayed vision of a man drinking milk (oh, right! Venus is pregnant) nearly ruined Wagner´s sublime ouverture, performed exquisitely under the baton of Christian Thielemann. This year´s audience may be lucky that the production has caused such a scandal. Thomas Hengelbrock refused to conduct this season after complaining that he had to constantly rehearse with a different set of orchestra players, and word has it that the cast is a notch up from the premiere.

I have never heard a German opera in which diction was so clear throughout. Torsten Kerl maintains a healthy voice despite having sung all of Wagner´s roles for tenor and consistently demonstrated clear dramatic purpose. Camilla Nylund was a lovely Elisabeth, with a creamy tone whose occasionally squally high notes were easily forgiven. Michelle Breedt was a rich voiced Venus, and the Hungarian baritone Michael Nagy demonstrated impeccable dynamic shading in the role of Wolfram von Eschenbach. Günther Groissböck brought a powerful bass to the role of Hermann, the Thuringian Landgrave. The remainder of the supporting cast and choruses left little to be desired. If only the staging hadn´t reprocessed the archetypal underpinnings of Wagner´s opera to such crass effect.

Christian Marthaler´s Tristan und Isolde, a 2009 production, represents a more understated approach that nevertheless falls just as flat. Any eroticism is stripped bare, much in keeping with drab sets by Anna Viebrock that appear to reference a 1920s luxury ship. This year´s revival, presided over by German director Anna-Sophie Mahler (rumor has it that Marthaler refused to return because of limited rehearsal time), apparently added a bit more physical contact between the ill-fated couple, but the love potion still seemed to have more of a disenchanting than aphrodisiac effect. The duet “O Sinke Liebe Nacht” featured Tristan and Isolde sitting side by side like retirees in front of a television. Fluorescent lighting is assigned special prominence to illuminate the night and day theme so central to the clandestine romance, yet it hardly took on enough symbolic meaning to animate the action. Marthaler saves some interesting moments for the last act when Kurnewal waves his arms as if trying to swim out of the nothingness, and all the characters except for the dying couple end up facing the walls of the ship´s barracks. Isolde covers herself with a sheet on the same bed where Tristan lay dying from Melot´s wound, a demystifying touch.

If it weren´t for conducting by Wagner veteran Peter Schneider, returning to the festival for the twentieth time, one might have secretly wished for the production to have ended sooner. Schneider´s taut, restrained reading was much in keeping with the vision onstage despite his swift pace. The level of technical perfection and power he cultivated from the orchestra often put the singers to shame, with a transcendent Liebestod that compensated for the magic lacking onstage. To be sure, uninspired as Marthaler´s production is, a more polished cast might have better risen above the odds. In this case, Robert Dean Smith was staid and underpowered as Tristan, while Irène Theorin—one of today´s best Wagnerian sopranos—was not in her best voice, nor did she make the text understandable. She still produced some touching piannissimi in the final scene and ripped through the score´s charged moments. Breedt did not disappoint as Brangäne, Isolde´s maid, but it was Jukka Rasilainen who commanded consistent attention with his smooth bass in the role of Kurwenal, Tristan´s servant. Kwangchul Youn was a powerful King Mark, and Ralf Lukas a vengeful Melot.

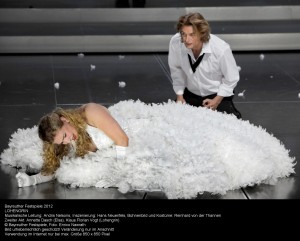

The finest production this season is hands down Stefan Herheim´s Parsifal, the only opera on the roster commissioned by Wolfgang Wagner. Herheim´s breathtaking allegorical vision begins at the Villa Wahnfried in the 1880s and ends at parliament in the Federal Republic of Bonn a century later. The story integrates elements from a medieval saga by Wolfram von Eschenbach that served as a source for Wagner´s libretto, inserting a silent actress as Parsifal´s mother, Herzeleide. Most likely with reference to Cosima Wagner, she lies in bed at the center of the Villa´s living room, copulating with her son in dream-like visions (namely when Amfortas holds up a glowing grail) and giving birth to a baby which then appears to be circumcised. Such moments were perplexing and somewhat gratuitous, but Herheim´s keen attention to the dramatic structure of Wagner´s score and the impeccable handwork of his team (sets by Heike Scheele and costumes by Gesine Völlm) redeems even what bordered on the offensive. The walls of Wahnfried were recreated verbatim yet haunted in a surrealist vision of black-winged beings and Parsifal as a young boy, only morphing slightly with hospital beds and mirrored walls for Klingsor´s magic castle, a brothel for the wounded.

Herheim is mostly a genius of subversion, effectively sublimating Christian and inherently anti-Semitic references into a commentary on German politics, such as when a chorus of World War One soldiers passes around bread in the Knight´s chorus, “Nehmet vom Brod/wandelt es kühn,” of the first act or when Amfortas, his head still crowned in thorns, takes the podium in the final tableau and utters “Wehe” to a room of bureaucrats while Kundry and Gurnemanz stand outside a proscenium reproducing the pillars lining the stage of the Festspielhaus—a re-consecration of the stage. Despite the politicization of the opera, a film interlude imitating the credits of the black and white era (video by Momme Hinrichs and Torge Moller) asks audience members to refrain from political debate, quoting the Wolfgang and Wieland Wagner adage “Hier gilt`s der Kunst” (Art reigns here)—a value which helped restore the festival to family hands following the American occupation. This will be the last revival of the 2008 production, but much like Chéreau´s Ring, one imagines that subsequent directors will have a very hard time overcoming its legacy—although Jonathan Meese is likely to stir up his own (succéss de) scandale with his 2016 rendition of Parsifal.

Musically, Herheim had a solid cast with Burkhard Fritz as Parsifal, whose reliable Heldentenor and portly presence were well suited to the role within this artistic vision. The dramatic demands were even higher on Susan Maclean as Kundry as she magically changed forms, and although her voice revealed some strain, her keen expressive powers served to pull off the role effectively. Kwangchul Youn was the vocal stand-out of the evening as the veteran knight Gurmemanz, anchoring the production with his mellifluous bass, while the vocal weaknesses of Detlef Roth only made him a more vulnerable, pious Amfortas. Thomas Jesatko brought crisp singing to the role of the magician Klingsor, promiscuously appearing in pantyhose and a tuxedo shirt, and Diogenes Randes rounded out the cast well as Titurel. The Swiss conductor Philippe Jordan, in his Bayreuth premiere, lived up to the family name (his father, Armin, being a well-known champion of the opera at hand) with an account of Wagner´s score as elegant and sensuous as one might dream, transparent, mysterious, and enchanting. Orchestra playing like this deserves a staging as aesthetically ravishing and intellectually challenging as Herheim´s, reminding us that the creation of something new is not enough: great art has always had the power to move not only its contemporaries but generations centuries later.