by Sedgwick Clark

I’ve been promising to run photos from our African vacation in this space almost since we returned two months ago. The lone dissenter (“You’re not really going to post photos from your Safari on Musical America.com!! Oy.”) was far outvoted. Only yesterday I ran into a friend who had seen photos posted in a decidedly more timely fashion on our fellow traveler Peter Clark’s Facebook page, and she expressed interest in seeing more. It was difficult to choose from all we took, and I may even have more next week.

The trip was planned by ROAR AFRICA, which we all agreed thoroughly lived up to advance praise. We flew to Johannesburg but after a four-hour layover continued to Cape Town rather than face the former’s notorious crime level. Both of the cities’ airports were strikingly up-to-date and clean, however. Once in Cape Town, we were met by ROAR AFRICA guide Andy Ward, a retired geography teacher, who had the answers for all of our questions and made us feel completely safe and at ease.

Exploring the wine lands and partaking in wine, goat cheese, and chocolate (!) tastings was a relaxed way to overcome 20-some hours of travel. We also visited the Spier Wine Estate, which houses a bird sanctuary and a Cheetah Outreach Program where over 20 of these beautiful, endangered cats live.

We also visited the Hout Bay Music Project, which I wrote about on May 24, while still in Africa. We took so many photos that I’ll put a few of them together in a future week of their own.

The first three photos cover our time in Cape Town before flying east to Kruger National Park, where more colorful beasts roam. All photos were taken by yours truly or Peggy Kane unless otherwise noted.

Many thanks to Stephanie Challener for her assistance in posting these photos.

(left to right) The intrepid travelers: Peter Clark, Sedge, Peggy Kane, and Jonathan Rosenbloom at the Cape of Good Hope.

Nelson Mandela’s prison cell for 18 years on Robben Island. The Dutch settled the Cape in the mid-1600s and established the island primarily as a prison. Since 1997 it has been a living museum and a focal point of South African heritage, with tours given by former prison inmates.

Sedge and Peggy on 3,000-foot Table Mountain with Cape Town in background to the west. Possessed of an unfortunate urge to jump from such heights, I dared venture no further out onto this overlook’s precipice, to Peggy’s amusement. Many young visitors would lean over the railing, presumably to enjoy the precipitous drop, but compelling me to head for center ground. On our 3,500-foot descent in the cable car, to avoid the 360-degree views afforded by the car’s revolving floor, I kept my cookies down by engaging our guide Andy in an eyes’-locked discussion about the upcoming American presidential election.

Safari at dawn with tree and crescent moon. Bush safaris in the Tinga and Lion Sands Game Preserves were from 6-9:00 a.m. and 4-7:00 p.m., returning to camp for breakfast and for dinner, respectively. In between, we could watch the elephants cavort in the Sabie River or take a nap.

It’s a matter of pride for the safari rangers and trackers to find the Big 5 (lion, leopard, elephant, rhino, and buffalo), as well as hippo and giraffe. A tip from a fellow ranger led us to this scene. The giraffe had been killed by different lions three days before, and these lions (pictured) had ventured out of their own territory from a neighboring park across the Sabie. Before we approached the kill, our ranger stopped the Land Rover and plucked fever bush leaves for each of us to smell. We were very grateful.

A hippo close-up on a walking tour. Unlike when we were safely seated in the Land Rover, our ranger and tracker each carried a rifle. We were warned that if he should turn on us and charge, the worst thing we could do would be to run! Fortunately he lumbered off into the river.

Of the Big 5, elephants are the most prolific. We have photos of them everywhere, crossing highways, jamming traffic as they lumber down dirt safari roads, knocking down trees to eat their roots, crossing the Sabie River.

A crocodile lies in wait beneath weaver bird nests, while two terrapins clamber out of the water and a white heron keeps watch.

Despite reassurance that this family of grazing rhinos was allowing us into its territory, being just 20 feet from this most prehistoric-looking of living animals generated a palpable sense of awe and danger.

Books: George Szell; the New York Philharmonic

July 26th, 2012by Sedgwick Clark

For a couple of years I’ve been putting off even mentioning some worthy books whose authors happen to be good friends. Perhaps I should have taken the old New Yorker answer to books by its contributors and simply listed them without comment. At this late date, I suggest you simply buy these books.

George Szell once told Time magazine that no one would ever write a biography of him: “I’m so damned normal.” No one who knew this podium tyrant believed his self-appraisal for a second. Certainly not his Cleveland Orchestra musicians, who called him “Cyclops,” only partly due to his Coke-bottle thick glasses. Nor Rudolf Bing, famed general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, who clashed with Szell in 1953-54 when he abruptly stormed out of his contract with the company. Someone said to Bing afterwards that Szell was his own worst enemy. Bing’s famous reply: “Not while I’m alive.”

Michael Charry’s George Szell: A Life of Music (Illinois, 2011) is the first book about one of history’s great conductors, and it is likely, given the current lack of commercial interest in classical music, to be the only one. So thank you Illinois Press, and thank you Michael Charry, who had a front-row-center view of this prickly musician for nine years as a member of the Cleveland Orchestra’s conducting staff and apparently remembered everything. His admiration for Szell never flags, yet he allows us to see the conductor’s cruelty to his players when they performed imperfectly as well as his kindness to such impressive young soloists as German violinist Edith Peinemann and American pianists Leon Fleisher, Gary Graffman, and John Browning. In the judicious balance of reported information and his own observations, Charry has crafted a biography worth waiting for. Importantly, a list of Szell’s repertoire and a complete discography are included—the last time in our computer age I expect to see this.

New York Philharmonic concertgoers over the past six decades will want to read John Canarina’s The New York Philharmonic: From Bernstein to Maazel (Amadeus Press, 2010), a sequel of sorts to critic and journalist James Huneker’s The Philharmonic Society of New York and Its Seventy-Fifth Anniversary (1917) and conductor/teacher Howard Shanet’s Philharmonic: A History of New York’s Orchestra (Doubleday, 1975). While I haven’t read the Huneker book, he was reportedly rarely without strong opinions; nor is Shanet, who uses his book to combat “the vast, and largely unjustified, inferiority complex that has oppressed American music throughout its history . . . .”

Unlike Shanet, Canarina has no “ax to grind.” He takes a historical tone, writing of what he considers the high points of concerts and important facts. Both authors had connections with the orchestra and conducted it—Shanet was a musical assistant to Leonard Bernstein in the early 1950s, and Canarina was an assistant conductor of the Philharmonic in 1961-62, during Bernstein’s tenure. Shanet ended his book before Pierre Boulez’s tenure began in 1972-73. Canarina, however, instead of beginning his book with Boulez, chooses to overlap with Bernstein’s directorship (1958-69), ending with Lorin Maazel’s tenure (2002-09).

It’s a fair but surprisingly dispassionate book, perhaps because conducting and teaching kept the author out of town during much of that time. Hence the reliance on what critics reported. It was Bernstein’s final season when I arrived in New York 44 years ago, and I enjoyed being transported back to the many Philharmonic concerts I have heard since that time. Canarina quotes many reviews with which I disagreed then and which annoy me still. That’s horse racing, to be sure, but I could have welcomed Canarina’s book even more if it had offered completely fresh opinions.

What Attorneys Won’t Tell You

July 25th, 2012By Brian Taylor Goldstein

I recently attended an arts conference where there was a panel discussion on music contracts. An attorney said that artists don’t really need to read or review contracts because you can always declare them null and void later and get a new contract. Is this true?

This is why 99% of most attorneys give the rest of us a bad name. No. It’s not true. That is, its bad advice. However, there are many attorneys out there who like to believe otherwise.

You may…or may not…be surprised to learn that any attorney with even the most minimal amount of skill can create some plausible “theory” on which to sue someone else. That’s all it takes to file a lawsuit in a US court: a plausible “theory.” Your theory might be the world’s dumbest theory, but everyone is entitled to his or her day in court. And, under what’s called the “American Rule”, unless there is a contract requiring the loser to pay for attorney’s fees and costs, everyone is responsible for their own attorney’s fees regardless of who wins or loses. So, unless you and I have a contract requiring the loser in a lawsuit to pay the winner’s attorney’s fees, I could technically file a lawsuit against you right now (assuming I knew who you were) and you would have to spend your own money to defend it. (If you don’t like the “American Rule”, blame George Washington. The “English Rule”, of course, is the exact opposite!)

Because of this situation, many attorneys believe that the answer to every conflict is to file a lawsuit and use that as leverage to get a better deal. The argument goes something like this: If an artist signs a contract and later wants to get out of it, just file a lawsuit claiming that the other side is in breach. Even if the artist has absolutely no legal basis for such a claim, the other side will need to hire their own attorney, file a motion, appear in court, and have the claim dismissed. As this will cost them thousands of dollars, the other side just might re-negotiate with rather than spend all that money. Here’s the catch: the artist will ALSO have to spend all that money hiring an attorney to file the lawsuit in the first place. And if you think that a large recording label, or a successful producer, or even a presenter with access to a free board attorney is simply going to roll over to avoid a lawsuit, think again. Why? Because their own attorneys will advise them to fight.

There’s another consideration, too: your reputation. One of my clients once received a letter from an attorney who represented an artist who was part of my client’s roster. Even though his contract was not up for another year, the artist wanted to be released early so he could negotiate a potentially lucrative deal directly with one of the producers we were already working with on his behalf. His lawyer raised several legally weak arguments and threatened a multi-million dollar lawsuit. After several efforts to resolve the matter ended in screaming phone calls and more threatened litigations, we decided to release the composer, even though, ultimately, I felt we would win in court. It simply wasn’t worth it. My client had other artists and business to focus on and could afford neither the money nor the time and distraction. While you may conclude that the artist got what he wanted and won, think again. There’s more: of course, we had to advise the producer that we no longer represented the artist and what had happened. As a result, the producer determined that the artist’s talents were not worth the risk of dealing with someone who sues their way out of a dispute and selected another artist for the project. It wasn’t long before word spread that this artist would sue anyone at anytime and other producers refused to work with him either. In the end, the artist’s lawyer wound up suing the artist for unpaid attorney’s fees. Not a happy ending.

If you haven’t figured out the game yet, an attorney will always advise you to file a lawsuit. However, regardless of the outcome, only the attorneys win. So, unless you have an endless supply of money, energy, time, and spirit do not play this game! Take the time to draft meaningful contracts, take the time to read them, and take the time to establish a relationship with the people you will be working with. You may not always get what you want in a negotiation, but at least you can make an informed decision by asking questions and evaluating the pros and cons of the deal before you. While there are many reasons you might agree to unfavorable terms, believing that you can sue your way out of a bad situation is not among them…unless you’re an attorney!

__________________________________________________________________

For additional information and resources on this and other  legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

To ask your own question, write to lawanddisorder@musicalamerica.org.

All questions on any topic related to legal and business issues will be welcome. However, please post only general questions or hypotheticals. GG Arts Law reserves the right to alter, edit or, amend questions to focus on specific issues or to avoid names, circumstances, or any information that could be used to identify or embarrass a specific individual or organization. All questions will be posted anonymously.

__________________________________________________________________

THE OFFICIAL DISCLAIMER:

THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE!

The purpose of this blog is to provide general advice and guidance, not legal advice. Please consult with an attorney familiar with your specific circumstances, facts, challenges, medications, psychiatric disorders, past-lives, karmic debt, and anything else that may impact your situation before drawing any conclusions, deciding upon a course of action, sending a nasty email, filing a lawsuit, or doing anything rash!

Feldman’s ‘Neither’ gets a Virtual Orchestra; A l’Arme! Festival for Contemporary Jazz

July 20th, 2012By Rebecca Schmid

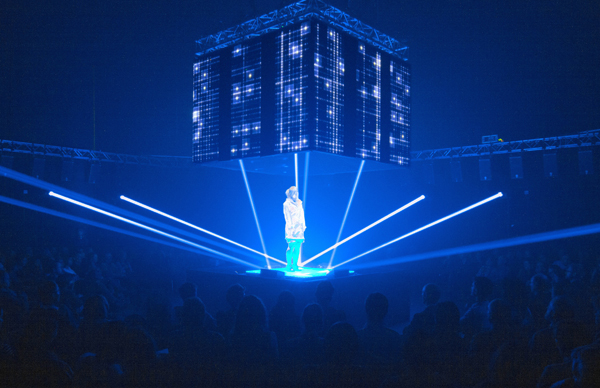

In an age of pervasive digital technology and avatars, it was only a matter of time before virtual experience infiltrated the concert hall. No handmade reeds, no tailcoats. Instead, over 70 synthesized speakers encircling the audience. The Berlin-based ensemble phase7, for a new production of Morton Feldman’s opera Neither, has replaced the live orchestra with 3D surround sound created through the spatial audio production procedure of wave field synthesis. The soprano Eir Inderhaug, trapped in a cage of light beams, provides the only human presence. The production premiered at the Festspielhaus Hellerau in Dresden last March before coming to the Radialsystem this month as part of the festival “The Art of Listening,” which included a conference chaired by the University of Potsdam.

A panel discussion following the concert, seen June 13, concluded that new formats were instrumental in preserving the classical tradition as it struggles to assert its value in today’s society, emphasizing that individuals’ different ways of listening must be addressed both in education and in the concert hall. The Radialsystem, founded in 2006 as a creative arts space, champions experimental modes of presentation such as late-night listening in which audience members can stretch out on yoga mats and musical wine tasting. As a positive sign for the future—even for those who prefer certain formalities of the concert hall—the Kreuzberg venue also attracts listeners who do not constitute a regular following for Berlin’s mainstream classical institutions.

A casually-dressed crowd filled the small back space of the Radialsystem’s main concert hall for Neither, given a clubby atmosphere with the help of smoke machines. Whirring surround sound amplified the static, high-pitched tones of Feldman’s opening bars as the first beams of light broke through the darkness. Inderhaug, a very pregnant figure dressed in all white, crouched silently on her platform at the center of the room. Yet the screeching faded mysteriously after about five minutes. A woman in a backpack emerged matter-of-factly to inform the audience: “as you know, there is a small technical problem,” as if such occurrences were par for the course. “Where is my conductor when I need him?” Inderhaug joked to the audience.

The experience was slightly demystified as the opera recommenced a few minutes later, this time traveling through churning industrial sounds and what sounded like a giant percussion set before yielding to the soprano’s existentially unresolved opening line, “to and fro in shadow from inner to outer shadow.” Neither, true to its name, is a negation of operatic convention and emerged after Feldman and Samuel Beckett discovered a mutual distaste for the genre upon meeting at Berlin’s Schiller Theater in 1976. Shortly thereafter, Feldman received a postcard with an 87-word verse that would provide the libretto for his monodrama, which premiered at Rome Opera the following year. Feldman’s economic, or minimalist, use of material—unsettling atmospheric drones, spiraling melodic figures, cavernous echoes—found an outlet in Beckett’s terse yet open-ended poetry.

The experience was slightly demystified as the opera recommenced a few minutes later, this time traveling through churning industrial sounds and what sounded like a giant percussion set before yielding to the soprano’s existentially unresolved opening line, “to and fro in shadow from inner to outer shadow.” Neither, true to its name, is a negation of operatic convention and emerged after Feldman and Samuel Beckett discovered a mutual distaste for the genre upon meeting at Berlin’s Schiller Theater in 1976. Shortly thereafter, Feldman received a postcard with an 87-word verse that would provide the libretto for his monodrama, which premiered at Rome Opera the following year. Feldman’s economic, or minimalist, use of material—unsettling atmospheric drones, spiraling melodic figures, cavernous echoes—found an outlet in Beckett’s terse yet open-ended poetry.As an “anti-opera,” the approximately 50-minute work lends itself well to phase7’s forward-looking concept, and yet the digitally-generated orchestra rarely proved its advantages over the more visceral experience of hearing live music. The metallic timbre of Feldman’s swelling chords, while often larger than life with this technology, took on a slightly digital quality that disengage the music’s emotional core, even as the sounds ricochet strategically from one speaker to the next. Visually, the isolation of the soprano, who hovers through an internal passage to an “unspeakable home,” is an effective dramaturgical solution to a work that does not lend itself easily to stage direction, yet holographic projections surrounding Inderhaug at times dehumanized the experience. On one occasion her stratospheric, incomprehensible tones made me think of the alien opera singer in The Fifth Element (vocal writing lies consistently above the treble clef, making it difficult to pronounce consonants, although a 1997 recording with Sarah Leonard and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra at least makes it clear throughout that she is singing in English).

It is a paradox that such events are touted as an innovative means of reviving classical music when orchestras throughout the western world are fighting to prove their raison d’être, and in some cases struggling to survive. As it happens, the same orchestral technology employed by phase7 was just on display at the Sydney Opera House for a production of Korngold’s Die Tote Stadt. That classical formats must evolve along with certain contemporary social trends is without question—video projections, DJ shows, and some degree of genre-bending will likely become standard fare for orchestras in future decades—but digital technology is no replacement for a gathering of trained musicians who rely on their brains rather than a circuit board. It is of course counterproductive to fight a certain amount of inevitability: the iPod and internet aesthetics may have already influenced the way we experience all kinds of music. 3D surround sound could provide a myriad possibility of tools to composers and be combined with live orchestra to powerful effect, but as Leonard Bernstein once said, music is about “flesh and blood.”

A l’Arme!

Despite Berlin’s growing reputation as the European mecca of the avant-garde, a platform for contemporary jazz was nowhere to be found until A l’Arme!, or Alarm (July 18-21) debuted at the Radialsystem this week. Bringing together artists from the U.S., Asia and across Europe, the program boasts artists such as the singer Neneh Cherry, returning from a 16-year hiatus in a new collaboration with the Scandinavian quartet The Thing, and German saxophonist Peter Brötzmann, something of a jazz icon on the continent. “There’s no better place than Berlin to burst open the cocoon of an entire scene whose self-absorbance is misunderstood as innovative,” state the program notes in a somewhat awkward translation. Indeed, it is no easy task to define free jazz. The movement emerged in the 1960s as a reaction to predetermined tonal structures, regulated timbres, and rhythmic conventions, eventually digging roots in Europe when the genre proved itself commercially untenable in the U.S.. Starting in the 70s, the term ‘avant-garde’ emerged as an alternative to describe this restless yet organized music, pioneered by figures such as John Coltrane, Sun Ra, and Ornette Coleman.

As evidenced by Alarm’s opening concert on July 18, a fine line often lies between what we call ‘new’ music in the classical realm and contemporary jazz. A trio formed by festival founder and pianist Louis Rastig with American clarinetist/saxophonist Ken Vandermark and Korean cellist Okkyung Lee opened with serialist patterns that were met with wild, meandering melodies and sawing, scampering motives. The musicians’ disparate improvisations managed to create a satisfying whole as frenetic, insistent patterns interwove with electric energy. A quieter middle section featured a repeated two-note figure in the piano, eventually picked up by a bass saxophone before Vandermark moved into squeaking slides and mechanical whirring. Rastig anchored the group with a charged physical awareness and strategic spontaneity, hitting across the keyboard with flat hands in child-like rebellion on more than one occasion, while Lee contributed a rumbling, shivering interlude that was sensitively echoed by Vandermark.

New York-based trumpeter Peter Evans opened the program with free improvisation demonstrating a virtuosic range of contemporary technique and multi-phonics. Muted trilling, wispy reverberations, exasperated blaring, raspberry blows—there is nothing Evans can’t create with his mouth and the valves of this instrument. The most impressive was his performance with a piccolo trumpet in which he broke out into traditional jazz melodies before reverting suddenly to gasping and sucking noises, creating an ironic halo of nostalgia around the sanguine 1950s style. His last act involved the simultaneous playing of a normal-sized trumpet against the piccolo, fluttering the valves of one instrument against the siren-like blare of the other. When Evans pushes through the call of the trumpet in full force, it is as if the instrument’s internal force has been stirring anxiously behind decades of experimentation.

The main hall of the Radialsystem spilled over with fans for The Cherry Thing, as one-time blockbuster Neneh Cherry dubbed her appearance the with The Thing in reference to their album which was released last month. The ensemble’s jazz-rock idiom is not an obvious match for Cherry’s smooth, hip-hop grooves, but she proved herself fearless enough to give a raspy (and slightly inaudible) scream over the cacophony of Mats Gustafsson’s indomitable saxophone, Paal Nilssen-Love’s across-the-board drums and the electric guitar of Ingebrigt Haker-Flaten in the opening number. The following song “Dream baby dream,” with its cooing vocals over saxophone and double bass in a unison melody that yielded to tonal counterpoint over soft drumming, proved a more effective blend. The Thing’s angry riffs lent themselves well to “Cashback:” you eat me for breakfast when you feed me… you spend me like money, sang Cherry over a catchy beat, her curls bouncing freely as she moved around stage in a black dress and sneakers. Ultimately it was unfortunate to experience this music in a seated hall; such danceable fare lends itself better to a small club, where listeners can chat quietly or sway with the music, and more vehement rock passages were too loud for the space. Still, it is exciting to have more intellectually challenging avant-garde fare combined with music of more popular appeal under one roof. A l’Arme has filled a niche that is likely to grow as jazz musicians of all breeds experiment with new outlets of expression.

The main hall of the Radialsystem spilled over with fans for The Cherry Thing, as one-time blockbuster Neneh Cherry dubbed her appearance the with The Thing in reference to their album which was released last month. The ensemble’s jazz-rock idiom is not an obvious match for Cherry’s smooth, hip-hop grooves, but she proved herself fearless enough to give a raspy (and slightly inaudible) scream over the cacophony of Mats Gustafsson’s indomitable saxophone, Paal Nilssen-Love’s across-the-board drums and the electric guitar of Ingebrigt Haker-Flaten in the opening number. The following song “Dream baby dream,” with its cooing vocals over saxophone and double bass in a unison melody that yielded to tonal counterpoint over soft drumming, proved a more effective blend. The Thing’s angry riffs lent themselves well to “Cashback:” you eat me for breakfast when you feed me… you spend me like money, sang Cherry over a catchy beat, her curls bouncing freely as she moved around stage in a black dress and sneakers. Ultimately it was unfortunate to experience this music in a seated hall; such danceable fare lends itself better to a small club, where listeners can chat quietly or sway with the music, and more vehement rock passages were too loud for the space. Still, it is exciting to have more intellectually challenging avant-garde fare combined with music of more popular appeal under one roof. A l’Arme has filled a niche that is likely to grow as jazz musicians of all breeds experiment with new outlets of expression.

Epiphanies and Masochism

July 18th, 2012by Sedgwick Clark

An Irresistible Concert

So soon after declaring my relief at being able to put my concert calendar on hold in the summer, Le Poisson Rouge presented a program too irresistible to miss, with three well-known chamber musicians at the top of their form: violinist Harumi Rhodes, cellist Caroline Stinson, and pianist Molly Morkoski in Ravel’s Sonate posthume pour violon et piano, Messiaen’s eight Préludes pour piano, Takemitsu’s Distance de Fée for violin and piano, Debussy’s Sonate pour violoncello et piano, and Piazzolla’s Verano Portena for piano trio, from The Four Seasons.

One of the best concerts I heard all year.

A Modest Epiphany

There’s a moment in Woody Allen’s new film To Rome with Love when a woman lost in Rome and late for an appointment drops her cell phone down a sewer grate. The unison gasp of horror from a full house at Lincoln Plaza Theaters was my biggest laugh of the evening.

Masochism on Broadway

Tracie Bennett’s all-stops-pulled portrayal of Judy Garland’s last three months of drugs, drink, and depression in Peter Quilter’s End of the Rainbow at the Belasco Theatre is a study in masochism—although whose I’m not sure—and she relives it eight times a week. Most of us raised on The Wizard of Oz are aware that Garland’s brief glimpse of the rainbow ended in tragedy, but for many, this Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf treatment may be too much to bear in a night on the town.

Bennett is remarkably convincing, the supporting cast is first-rate, the five musicians are excellent, the restored Belasco is a beauty to behold, but this is definitely not Mary Poppins.

Do We Need Visas For Orchestra Support Staff?

July 18th, 2012By Brian Taylor Goldstein

Dear Brian:

We are touring an orchestra in the United States next season and have been grappling with the idea of whether the staff from the concerts team need to have visas for this tour, regardless of whether they are employees or freelance (we’ve had different opinions expressed). In the past, we have always included our orchestral manager on the visa petition because she is a full time employee, but the concerts team staff are rather different, not least because they are usually hired only for the tour, nothing else, and will not be on tour for the whole time and are therefore not an intrinsic part of the artistic production. They receive no payments or salary in the US and, thus, earn no income in the US. Do you have any thoughts on this? If we get them visas, would they all have to travel together? Would we need two separate petitions? Does this cost more depending upon the size of the concerts team?

The need for a US work visa (O or P) is triggered by work, not payment. Anyone who provides services in the US, whether on the stage as a performing artist, or behind the scenes as part of the technical crew, administrative staff or tour support team, all require work visas–regardless of whether or not they are paid in the US or whether or not they are even paid at all. Whether or not they are an intrinsic part of the artistic production doesn’t change this.

In the case of orchestras, each of the musicians will require a P-1 visa and each of the non-performing support staff require a P-1S visa. To obtain these visas, you will need to file two visa petitions: a P-1 petition for the performers, conductor, musicians, etc. and a P-1S petition listing the technical crew, management team, administrative support, etc. Filing fees are charged “per petition”, so it costs the same whether the P-1S petition contains 2 people or 20 people. Once approved, each individual listed will need to appear personally at the US consulate and pay a visa fee before being issued his or her visa by a brusque and surly consulate official. P-1 and P-1S visas are valid for the duration of the approved classification period. So, the support staff is free to travel in and out of the US during the tour as needed. Everyone neither has to travel together nor do they have to remain for the duration of the entire tour.

Without exception, in the visas we prepare for our orchestral clients, we simply put all the musicians on a P-1 and all non-musician staff on a P-1S and eliminate the ability of a border guard to frustrate a process already fraught with enough risk and unpredictability from other areas.

_________________________________________________________________

For additional information and resources on this and other  legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ftmartslaw-pc.com.

legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ftmartslaw-pc.com.

To ask your own question, write to lawanddisorder@musicalamerica.org.

All questions on any topic related to legal and business issues will be welcome. However, please post only general questions or hypotheticals. FTM Arts Law reserves the right to alter, edit or, amend questions to focus on specific issues or to avoid names, circumstances, or any information that could be used to identify or embarrass a specific individual or organization. All questions will be posted anonymously.

__________________________________________________________________

THE OFFICIAL DISCLAIMER:

THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE!

The purpose of this blog is to provide general advice and guidance, not legal advice. Please consult with an attorney familiar with your specific circumstances, facts, challenges, medications, psychiatric disorders, past-lives, karmic debt, and anything else that may impact your situation before drawing any conclusions, deciding upon a course of action, sending a nasty email, filing a lawsuit, or doing anything rash!

Can Newspapers Charge To Quote Reviews??

August 8th, 2012By Brian Taylor Goldstein

Dear Law & Disorder:

I recently came across the website of an artist management agency in Europe where they had posted the following: “The press review is temporarily not available. German newspapers Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and Süddeutsche Zeitung recently started to pursue institutions and artists using texts (press reviews, interviews, commentaries etc.) published by those newspapers on their websites or in any other commercial context without having paid for them. We have been advised to remove all press quotations from our website as the same phenomenon seems to happen in other countries like Switzerland and Austria.” Is this a copyright trend that will spread to other European countries and the USA? Will agents, and artists have to start paying for the use of (press reviews, interviews, commentaries) used to promote an artists career? Also, if an American agency has press reviews, interviews, commentaries from Europeans newspapers on their websites, such as from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and Süddeutsche Zeitung, will these agencies be liable for payment of the use for this information, as well, as it is being used in a commercial context? (Thank you for your column on Musical America, and I also thank Ms. Challener for her leadership in including such information in the weekly email Musical America updates.)

Newspapers and magazines have always owned the exclusive rights to the articles, reviews, editorials, and interviews they publish. Just like you can’t make copies of sheet music, CDs, books, and other copyrighted materials, you cannot make copies of articles and reviews and re-post them without the owner’s permission. Even if you are not “re-selling” an article or review, anything that is used to promote, advertise, or sell a product or service (ie: an artist!) is a “commercial” use.” While “quoting” or “excerpting” a positive review is most often considered a limited “fair use”, making copies of the entire article or review is not. While it should go without saying, you also cannot “edit” or revise articles and reviews in an effort to make a bad review sound more positive. (That’s not only copyright infringement, but violates a number of other laws as well!)

The website you encountered was in response to certain German newspapers, in particular, who began making significant efforts to require anyone who wanted to copy or quote their articles or reviews to pay a licensing fee. In the United States, for the most part, most newspapers and magazines have not actively pursued agents or managers who have quoted articles and reviews on their websites to promote their artists. However, I am aware of managers and agents who have been contacted by certain publications where entire articles have been copied and made available for download. In such cases, the publication has demanded that the copy either be licensed or removed. I also know of agents and managers who have posted unlicensed images on their websites and then been contacted by the photographers demanding licensing fees.

As for the ability of an American agent to quote or copy articles from the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and Süddeutsche Zeitung, under the applicable international copyright treaties, they could require American agents to pay as well. While I don’t necessarily see this becoming a trend among US publications, its certainly worthwhile to reflect that anytime an agent, manager, or presenter uses images, articles, videos, other materials to promote an artist or performance, there are copyright and licensing considerations that need to be taken into consideration.

________________________________________________________________

For additional information and resources on this and other legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

legal and business issues for the performing arts, visit ggartslaw.com

To ask your own question, write to lawanddisorder@musicalamerica.org.

All questions on any topic related to legal and business issues will be welcome. However, please post only general questions or hypotheticals. GG Arts Law reserves the right to alter, edit or, amend questions to focus on specific issues or to avoid names, circumstances, or any information that could be used to identify or embarrass a specific individual or organization. All questions will be posted anonymously.

__________________________________________________________________

THE OFFICIAL DISCLAIMER:

THIS IS NOT LEGAL ADVICE!

The purpose of this blog is to provide general advice and guidance, not legal advice. Please consult with an attorney familiar with your specific circumstances, facts, challenges, medications, psychiatric disorders, past-lives, karmic debt, and anything else that may impact your situation before drawing any conclusions, deciding upon a course of action, sending a nasty email, filing a lawsuit, or doing anything rash!

Tags: agent, artist, Brian Taylor, cannot make copies, commentaries, commercial context, copy, copyright, copyright infringement, european countries, Goldstein, license, Licensing, manager, permission, photograph, quotations

Posted in Artist Management, Arts Management, Copyrights, Law and Disorder: Performing Arts Division, Licensing | Comments Closed