By ANDREW POWELL

Published: December 11, 2014

MUNICH — Puccini lost even before the curtain went up Nov. 15 on Hans Neuenfels’ conceptual new staging of Manon Lescaut for Bavarian State Opera. Anna Netrebko, its titular star, abandoned the project in quiet disgust, understandably it turned out. Disaster did not follow, but the night and the subsequent run will long be remembered for what might have been, musically.

The company broke the sorry news Nov. 3 after securing a substitute in Kristine Opolais. It cited “unterschiedlichen Auffassungen,” divergent opinions, between star and director and lamely lamented the stresses of theater life. It had not, apparently, considered managing those stresses so that no cast change was needed. In any case, the neat explanation rang hollow: Netrebko has a history of flexibility with Regietheater. She had signed on with a régisseur known for strange concepts and was no doubt looking forward to the highly visible introduction to Germany of a successful new role.

Sure enough, a more accurate picture emerged within days, in Der Spiegel and from the horse’s mouth. While the Russian soprano remained atypically mute, Neuenfels, 73, echoed the conversation in rehearsals that caused the rift. Netrebko had conveyed views about the choice facing Abbé Prévost’s 1731 material girl — between a life of passion with penniless des Grieux and one of wealth with Geronte — that he, Neuenfels, found “lächerlich und degradierend,” laughable and degrading, to women. He had reasoned back: “Möglicherweise findet man es in Russland als Frau gar nicht schlimm, sich von einem alten, reichen Mann aushalten zu lassen,” or, Maybe in Russia it is not considered at all bad for a woman to let herself be kept by an old rich man — this, not incidentally, to an actress whose own family endured deprivation and hunger at the start of her career. Bottom line: your views are no good, and probably because you are Russian. Bravo, Herr Direktor!

The cast change would not have mattered so much had Netrebko not triumphed in February in her role debut as Puccini’s Manon, and before an Italian audience under Riccardo Muti’s strict tutelage. But she had. Tapes demonstrate she was red hot for this role this year, with clear Italian, a dramatic command of the evolving character gleaned from years as Massenet’s protagonist, and, especially, rich tones to wield in all sorts of expressive ways.

Opolais has sung here often since her radiant first appearance in 2010 in a lyrically conducted (Tomáš Hanus), perversely staged (Martin Kušej) Rusalka, not always equaling that achievement. She is an enchanting presence on stage, an excellent musician, a game and cooperative colleague. The voice never makes an ugly sound, but it wanes in volume as it descends (there is no “chest voice” of substance), and her Italian wants stronger consonant projection.

On opening night Opolais (pictured) teamed magnetically with her des Grieux, Jonas Kaufmann. Both gave their best in Act IV, she singing to the boards for heft in Sola, perduta, he sailing high as a generous embodiment of Gallic desperation. Throughout Act II, alas, the soprano’s relatively monochromatic voice and missing gravitas limited the music: a little morbidezza helps in the singing of In quelle trine morbide, and Tu, tu, amore! Tu? at the start of the duet requires intensity and volume. Markus Eiche, as the immoral Lescaut, sounded glorious but strove in vain for italianità. Ditto for Sören Eckhoff’s loosely regimented choristers. Vivid supporting contributions came from Okka von der Damerau, a vocally lush Musico; Dean Power, a spright Edmondo; and the veterans Ulrich Reß, cast inexplicably as a hypertrichotic Maestro di ballo (hand is pictured, lower left), and Roland Bracht, a credible and clear Geronte.

The Bavarian State Orchestra showed astonishing sensitivity to Puccini’s freshest score, finely tracing its melodic ideas, scampering through the momentary ironies, deftly tinting the myriad and occasionally peculiar textures. It was an evening of great acumen and discernment for the brass, notably the trombone group, where an oversized cimbasso provided discreet assistance. Everything came across new and instant as propelled by Alain Altinoglu, Munich’s first master Puccinian in many seasons.

Neuenfels’ staging, which returns next July and will be streamed, advances the action to “Irgendwann,” whenever. It is black, framed in white neon. Its black-clad protagonists emote under seldom-varied white light. Stripped of time and place, the French cautionary tale is spun with the aid of projected texts auf Deutsch, plugging holes the director perceives in the Italian libretto and injecting wisdom and whimsy, little of it profound or funny. Early example: “‘When a coach comes, the opera begins,’ said Giacomo Puccini.” Neuenfels uses the choristers — Act I’s students, Act II’s guests, the gawkers at Le Havre — to toy around more invasively, mockingly, endowing them with flame-red hair to ensure we watch.

The action is closely calibrated to shifts in the score, but the rootless and sterile settings, combined with Neuenfels’ propensity to play with paraphernalia and gags of his own invention, send the opera down a path that is at odds with the brutal application of law and the personal destruction driving the music. Result: a diminished dramma mitigated somewhat by a powerfully bare Act IV.

It is intriguing to contemplate how much of this production would still have worked had its director been fired last month after offending Netrebko. Chances are, all of it. One imagines a late but efficient Bavarian State Opera team scramble to prepare for opening night without Neuenfels, mounting Manon Lescaut with the planned and more gifted soprano. In business, it would have been that way, and one wonders why a public theater is any different. Instead the company’s management allowed hurtful on-the-job remarks to deprive Munich, and the world, of what would certainly have been a momentous series of performances. Prima il regista, poi la musica.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Verdi’s Lady Netrebko

Blacher Channels Maupassant

Portraits For a Theater

Petrenko’s Sharper Boris

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

Carydis Woos Bamberg

Sunday, January 4th, 2015By ANDREW POWELL

Published: January 4, 2015

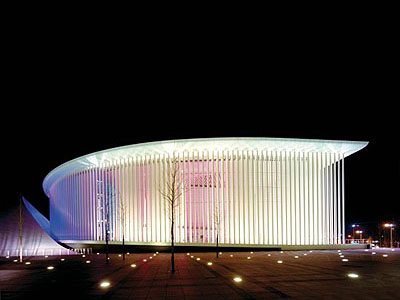

BAMBERG — When the Bamberger Symphoniker replaces its Chefdirigent next year, it could do worse than hiring Constantinos Carydis. The intense but discreet Athenian secured creative and technically superb playing in a Nordic and Impressionist program Nov. 29 here at the Joseph-Keilberth-Saal, confirming skills he has shown in Munich.

Choosing won’t be easy, and there is a preliminary question for this conservative north Bavarian town. Artistry or stability? Bamberg has enjoyed plenty of the latter in incumbent Jonathan Nott, who began in 2000. But unique interpretive approaches are another matter. The Lamborghini-driving British conductor has not forged a strong international profile for the orchestra — Edinburgh performances in 2011, for instance, lacked insight and vigor — and the claim of an “audible leap in quality” under his leadership versus the standards of predecessors Keilberth, Eugen Jochum and Horst Stein is hard to accept.

The job has attractions, not least the direct backing of the orchestra by the Free State of Bavaria, which encourages its deep tradition of touring. (Formed by German musicians expelled from Czechoslovakia, the Bamberger Symphoniker has given 6,500 concerts in 500 cities and still performs mostly away from home.) State broadcaster BR records the ensemble’s work and a few years ago the state helped pay for sound tweaks by Yasuhisa Toyota to its 1,380-seat hall. Built in 1993 with cheap materials and named after Bamberg’s grumpy first Chefdirigent, who held the post from 1950 to 1968, the Joseph-Keilberth-Saal sits on the Regnitz River below a onetime monastery. It probably is “Bavaria’s best concert hall” (another claim) if only because Nuremberg and Munich are so deficient in this regard. The sound is warm, balanced and natural, though high frequencies project relatively feebly.

Carydis, 40, definitely not to be confused with his vain compatriot Teodor Currentzis, 42, will be unlike anyone else the orchestra is considering and may or may not fit Bamberg’s concept of “maestro.” He is selective in the projects he takes on, i.e. not known for a heavy workload. For this debut he was without a jacket and looked disheveled. When in 2011 he was somewhat distressingly handed the Carlos Kleiber Prize — established on Kleiber’s 80th birthday and awarded only once to date, to Carydis — he disappeared for a year’s sabbatical. Not surprisingly he has never held a major music directorship and it is unclear whether he could commit to the scope of such a job. On the other hand, all that he does turns to musical gold. He is highly imaginative and perceptive, meticulous in preparation, equally accomplished in opera and symphonic music, adept in scores by such dissimilar composers as Shostakovich, Falla, Rimsky-Korsakov, Mozart and Offenbach. He is admired where he is best known, in Munich: tomorrow he will conduct a Brahms and Debussy concert, later this month a run of Don Giovanni, and during this summer’s Opernfestspiele a new staging of Pelléas et Mélisande.

This Bamberg concert followed runouts of the same program the previous two evenings in nearby Erlangen and Schweinfurt, part of the orchestra’s duty as a state ensemble. Refinement in the playing, no doubt lifted by repetition, came across immediately in Sibelius’s brute tone poem Tapiola (1926). The conductor reveled in its mostly quiet dynamics, lavishing attention on the woodwinds and propelling its long lines. Loud passages had considerable impact and the sense of purpose never flagged, though tension at times gave way to deathly stillness. In Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894), which followed, Carydis appeared to let flutist Daniela Koch pace and shape the music. She practiced the virtue of playing gently all through the concert, so that her instrument always sounded exquisite; in the Debussy she was guilefully supported by her woodwind colleagues and flattered by the satiny strings, but at its end it was the conductor’s collaboration she went out of her way to acknowledge.

Nielsen’s brooding nine-minute pastorale for orchestra Pan og Syrinx (1918) opened the second half of the concert as a preamble to Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé Suites 1 and 2 (1911 and 1913). Like the Ravel, it relies on a sensuous string sound but places the interest in the woodwinds (clarinet and cor anglais personify the protagonists); agitated outbursts prop up the longer ruminative material. The Bamberg musicians achieved delicacy and much expressive character here, and in the Ravel, always with attention to mood. Carydis permitted no applause before Ravel’s opening Nocturne and looked irked that the Danse guerrière — brilliantly controlled, indeed electrifying — caused an eruption of applause before he could proceed into the Second Suite.

No decision date has been publicly set for the Bamberg appointment (in contrast to the Berlin Philharmonic job, for which a successor to a different Briton will be named in May, to start in 2018 after an equal 16-year tenure). If the new chief on the Regnitz can artistically stretch the musicians, as Carydis did on this visit, he or she will have been better chosen than any long-staying routinier.

Photo © Thomas Brill

Related posts:

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

Wagner, Duke of Erl

Nézet-Séguin: Hit, Miss

Widmann’s Opera Babylon

Tutzing Returns to Brahms

Tags:Bamberg, Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, Bamberger Symphoniker, Commentary, Constantinos Carydis, Daniela Koch, Daphnis et Chloé, Debussy, Jonathan Nott, Joseph Keilberth, Nielsen, Pan og Syrinx, Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune, Ravel, Review, Sibelius, Tapiola

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed