by Sedgwick Clark

The New York Philharmonic’s three-week “Russian Stravinsky” festival ended on Saturday, and I miss it already. To be treated to this life-affirming music live in concert week after week by this superb orchestra was a rare opportunity. If there were a fire in my home, I’ll bet I would save my Stravinsky Conducts Stravinsky CD set on Sony Classical before any of my over 10,000 CDs.

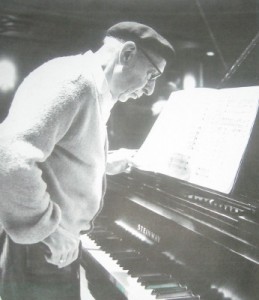

My own Stravinsky mania—which, I never tire of pointing out, was also the beginning of my classical-music mania—began in college with his Columbia stereo recording of Le Sacre du printemps. I immediately began to collect all of his recordings and now have three incarnations of the stereo ones and all the mono ones. Mind you, I had heard none of this music before, so the composer’s performances became my touchstone for the way to hear it played. Other conductors’ views paled in comparison, especially in terms of rhythm, articulation, and textural clarity.

I had the good fortune to attend two Stravinsky concerts the year before he retired from the podium. In spring 1966 Stravinsky and his amanuensis (strange word) Robert Craft led the Louisville Orchestra in concert: Fireworks and the Firebird Suite conducted by the composer and Le Sacre conducted by Craft. My school mates complained that I was tapping my feet too loudly. During winter break that year I again heard Stravinsky and Craft conduct, this time in Chicago for what was billed his “final appearance.” The 84-year-old composer led a pickup group (not the Chicago Symphony, although some of its players were moonlighting) in Fireworks, the fourth tableau from Petrushka, and the Firebird suite. I remember that at a certain point in the boisterous “Dance of the Coachmen” he stopped conducting and didn’t lift his right arm again until it was time to cue the scurrying “Mummers.” Craft accompanied a young Israeli violinist with dark, curly hair and an engaging smile who walked onstage on crutches and wowed the audience when a string broke in the composer’s Violin Concerto and he had to finish the piece with the concertmaster’s instrument. I also remember fondly that after the second curtain call the little composer shuffled out in his overcoat, smiled broadly, and waved to the wildly applauding audience, drawing his coat around his neck as if to say, “I’m cold, and I’m going now.” It was one of those Windy City winter nights. I had ignored my mother’s advice and brought only a raincoat when I drove from Muncie to Chicago. I have never been so cold since.

Valery Gergiev, who conducted the New York Philharmonic concerts, has quite a different style of performance than the composer. He arranged the participation of St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater Chorus and several singers from the Mariinsky Opera, of which he is music director, to heighten the “Russian” style he believes right for Stravinsky. Whatever the case, and despite the fact that in my estimation Gergiev’s performances had their ups and downs, I haven’t had such a stimulating time at the Philharmonic since the Boulez era.

Let’s look at how the composer felt his music should be performed before we look at Gergiev’s concerts one by one. In Conversations with Igor Stravinsky by the composer and Robert Craft (University of California Press, 1980, paper), the first of five books co-authored by the two, originally published in 1958, Craft asks him: “What do you regard as the principal performance problems of your music?” Stravinsky replies:

“Tempo is the principal item. A piece of mine can survive almost anything but wrong or uncertain tempo. (To anticipate your next question, yes, a tempo can be metronomically wrong but right in spirit, though obviously the metronomic margin cannot be very great.) And not only my music, of course. What does it matter if the trills, the ornamentation, and the instruments themselves are all correct in the performance of  a Bach concerto if the tempo is absurd? I have often said that my music is to be ‘read’, to be ‘executed’, but not to be ‘interpreted’. I will say it still because I see in it nothing that requires interpretation (I am trying to sound immodest, not modest). But you will protest, stylistic questions in my music are not conclusively indicated by the notation; my style requires interpretation. This is true and it is also why I regard my recordings as indispensable supplements to the printed music. But that isn’t the kind of ‘interpretation’ my critics mean. What they would like to know is whether the bass clarinet repeated notes at the end of the first movement of my Symphony in Three Movements might be interpreted as ‘laughter’. Let us suppose I agree that it is meant to be ‘laughter’; what difference could this make to the performer? Notes are still intangible. They are not symbols but signs.

a Bach concerto if the tempo is absurd? I have often said that my music is to be ‘read’, to be ‘executed’, but not to be ‘interpreted’. I will say it still because I see in it nothing that requires interpretation (I am trying to sound immodest, not modest). But you will protest, stylistic questions in my music are not conclusively indicated by the notation; my style requires interpretation. This is true and it is also why I regard my recordings as indispensable supplements to the printed music. But that isn’t the kind of ‘interpretation’ my critics mean. What they would like to know is whether the bass clarinet repeated notes at the end of the first movement of my Symphony in Three Movements might be interpreted as ‘laughter’. Let us suppose I agree that it is meant to be ‘laughter’; what difference could this make to the performer? Notes are still intangible. They are not symbols but signs.

“The stylistic performance problem in my music is one of articulation and rhythmic diction. Nuance depends on these. Articulation is mainly separation, and I can give no better example of what I mean by it than to refer the reader to W. B. Yeats’s recording of three of his poems. Yeats pauses at the end of each line, he dwells a precise time on and in between each word—one could as easily notate his verses in musical rhythm as scan them in poetic metres.

“For fifty years I have endeavored to teach musicians to play  instead of

instead of

in certain cases, depending on the style. I have also labored to teach them to accent syncopated notes and to phrase before them in order to do so. (German orchestras are as unable to do this, so far, as the Japanese are unable to pronounce ‘L’.)

“In the performance of my music, simple questions like this consume half of my rehearsals: when will musicians learn to abandon the tied-into note, to lift from it, and not to rush the semiquavers afterwards? These are elementary things, but solfeggio is still at an elementary level. And why should solfeggio be taught, when it is taught, as a thing apart from style? Isn’t this why Mozart concertos are still played as though they were Tchaikovsky concertos?”

PROGRAM 1 (April 22): Les Noces (1914-23); Symphonies of Wind Instruments (1920, rev. 1945-47); The Firebird (1909-10).

Gergiev stressed in interviews that the Mariinsky Chorus would make a big difference in our understanding of such a “Russian” work as Les Noces, but he tore through the piece in 22 minutes, over three minutes faster than the composer’s comfortably paced and far more expressively shaped stereo recording. Gergiev’s single-minded approach was exciting, to be sure, but it negated any advantage the chorus or his Russian soloists might offer. And try as he might to subdue the Russian pianists and Philharmonic percussion players, the vocalists were covered much of the time. For nine years and three different-sized performing groups, Stravinsky struggled to find a workable answer to Les Noces. Bernstein’s answer with the Philharmonic in 1970 was to amplify the vocalists and allow the instrumentalists to lam away full throttle—not, need it be said, successful either. Slow down, Valery, and choose a smaller venue next time.

Symphonies of Wind Instruments was played superbly by the Philharmonic winds—one of the highlights of the festival.

A broadly paced complete Firebird glimmered with subtle tone painting in Gergiev’s hands, with an uncommonly expressive “Khorovod” being the highlight of the performance. Imprecise playing dotted the violent “Dance of Kashchei,” however, and the finale could have unfolded with less fuss. Page turning by a few extra violinists in the back desks of the firsts and seconds was loud and distracting in fast passages.

PROGRAM 2 (April 23): Les Noces (1914-23); Symphony of Psalms (1930; rev. 1948);The Firebird (1909-10).

Gergiev hadn’t relaxed his relentless grip on Les Noces a day later. Symphony of Psalms had all its accustomed power in the first two movements, but the slow tempos of the final movement were inexplicably rushed—a great disappointment. I departed at intermission but regretted it when a friend reported improved ensemble in The Firebird.

PROGRAM 3 (April 29): Zvezdolikiy (1911-12); Violin Concerto in D (1931); Oedipus Rex (1926-27; rev. 1948).

What a strange little work Zvezdolikiy is, lasting only 5:40 in this performance. It’s also known by its French title, Le Roi des étoiles, or the American translation, The King of the Stars—or, in the program, The Star-Faced One. Unfortunately, on this occasion it was neither clearly played nor sung, and not helped by the lack of texts and translations; projected English titles just don’t suffice for such an unknown entity.

Another festival highlight was the Violin Concerto, with Gergiev and soloist Leonidas Kavakos setting brisk tempos and keeping Stravinsky’s dancelike rhythms chugging buoyantly along. The finale flew like a flash, with Kavakos digging in lustily and the Philharmonic’s principal French horn, Philip Myers, whooping away joyously toward the end. Talk about taking chances! The players clearly loved playing the concerto and applauded Kavakos warmly, as did the audience, so he played an encore.

So much of Gergiev’s way with Oedipus Rex was exciting that his impatience in some of Stravinsky’s most eloquent music was dispiriting. Take the opening, for instance, which has tremendous weight and gravity under Stravinsky but jogtrots casually in Gergiev’s hands. Or Jocasta’s aria which, despite Waltraud Meier’s fine singing, loses its stately grandeur at Gergiev’s pace. The duet between Oedipus and Jocasta was exciting in its violent propulsion, but textural clarity suffered and rhythms were inaudible; likewise for the chorus’s telling of Jocasta’s death. On the other hand, the final chorus was thrillingly intense. Dumbfounding, however, was the inconsistent pronunciation of Oedipus’s and Jocasta’s names by the otherwise impeccable Narrator, Jeremy Irons, for lord’s sake, and Anthony Dean Griffey’s Oedipus, who couldn’t keep his wife’s name straight!

PROGRAM 4 (May 30): Orpheus (1946-47); Oedipus Rex (1926-27; rev. 1948).

Orpheus is one of Stravinsky’s subtlest scores. In its quiet, Monteverdian way, it is no less powerful than Le Sacre, rising above mezzo-forte only once, when the Bacchantes attack Orpheus and tear him to pieces. It takes great artistry to sustain the music’s half-hour duration, and I am told it received only two hours of rehearsal the morning of this concert. It was the festival’s nadir—the worst performance I’ve heard from the Philharmonic in 20 years, although hardly the fault of the musicians. Only Nancy Allen’s harp playing escaped the overall dismal showing.

I had my score of Oedipus and noted, among other things, that Gergiev set a perfectly good tempo for the beginning of Jocasta’s aria and sped up at number 96, making it more difficult for Meier to articulate. The next day at a Morgan Library symposium, he told Joseph Horowitz that “For years I couldn’t find the key to Oedipus Rex.” He should keep looking.

PROGRAM 5 (May 2): Renard (1915-16); L’Histoire du soldat (1918).

As with Les Noces, Gergiev’s Renard was too fast for optimum clarity, phrasing, and character; the playing was excellent, but the composer’s recording is far more fun. As always in these concerts, his regard for the singers was slight, and his Russian basses were all but inaudible.

The Philharmonic players were at the top of their game in L’Histoire. Principal Associate Concertmaster Sheryl Staples has always shone herself to be one of the jewels of the orchestra, and she outdid herself here in some of the wittiest writing for violin in the literature. Joseph Alessi’s flatulent trombone squawks always hit the mark, as did the contributions of clarinetist Mark Nuccio, bassoonist Judith LeClair, trumpet player Philip Smith, percussionist Christopher S. Lamb, and double bass player Satoshi Okamoto. Alec Baldwin was a disappointing Narrator, delivering his lines in a flat, uninflected tone. Matt Cavenaugh was a vapid Soldier. Daniel Davis was delightful, a properly ironic and devilish Devil.

PROGRAM 6 (May 6): Symphony in C (1938-40); Capriccio for Piano and Orchestra (1928-29; rev. 1949); Petrushka (1911).

One wonders why the symphony is not played more often, but as one could sense here it’s damned difficult. Gergiev’s was a meaty performance and will do for the time being, although I hope to hear a truly spiffy reading someday.

The Capriccio was one of the composer’s favorite works—so much so, the late Philharmonic pianist Paul Jacobs told me many years ago, that when Columbia signed Philippe Entremont to record the Piano Concerto and Capriccio, and Stravinsky was not happy with the previous day’s recording of the former, he locked himself in his bathroom the morning of the Capriccio session and Robert Craft had to conduct the recording. I think Stravinsky would have found Denis Matsuev’s heavy, fingers-of-iron style totally lacking the puckish caprice of the work, especially in the second movement. It was assured and accurate but with no bounce or balletic twinkle. The accompaniment could have used a couple more rehearsals, as I’m sure it always does; it’s a rhythmic nightmare, and I can’t imagine it made a good showing for Stravinsky in the 1930s. The audience loved it, though, and Matsuev played an encore: Shchedrin’s Humoresque.

The Petrushka was okay, but nothing special.

PROGRAM 7 (May 7): Symphony in Three Movements (1942-45); Concerto for Piano and Wind Instruments (1923-24; rev. 1950); Le Sacre du printemps (1911-13).

Stravinsky’s mid-’40s “Victory” symphony received the best performance of the full-orchestra works in the festival, with the tightest ensemble and solo detail, and the extensive concertante parts incisively played by Philharmonic principals Nancy Allen (harp) and Jonathan Feldman (piano). Interestingly, Gergiev appeared more overtly concerned with ongoing rhythm and specific cues than in previous nights, and the results showed.

No performance I’ve heard (including recordings) of Stravinsky’s dour, neoclassical Piano Concerto has felt truly secure. The solo and ensemble writing never seems to interlock rhythmically, and it was no surprise to read in the program notes that Stravinsky had memory lapses while composing and performing the piece. (Perhaps he was wondering what double basses were doing in a work purportedly for piano and winds.) The festival’s underrehearsed reading was not helped by an unassertive soloist, Alexei Volodin. (Three days later, and only hours after typing these words, a reprise of the concerto occurred at Zankel Hall by the Ensemble AJCW under John Adams, with Jeremy Denk as soloist. The student wind players could not be mistaken for their Philharmonic counterparts, but they played accurately and enthusiastically, while Denk’s playing had all the rhythmic bounce and jazzy accents that Volodin lacked. Moreover, Adams’s conducting and Denk’s pianism dovetailed admirably.)

The festival had to conclude with Le Sacre du printemps—how else? It was first performed by the Philharmonic in 1926 under Wilhelm Furtwängler, of all people. Stravinsky recorded it with the New Yorkers in 1940. Boulez’s unforgettable first Sacre with the Philharmonic in 1969 won him the music directorship. I wish I could say that Gergiev’s performance was one for the ages. Tempos ranged wide, attacks were spongy, instrumental texture was mush. The fast music was exciting on a superficial level, but the lack of detail soon became wearing. Judith LeClair’s evocative bassoon solo in the Introduction to Part I and the superb ppp muted trumpets in the intro to Part II are the only moments that stand out positively in retrospect. The distended pause before, and treatment of, the final two chords was laughable. The orchestra and conductor were roundly applauded at the end, so what do I know?

Looking forward

My week’s scheduled concerts:

5/13 Avery Fisher Hall. New York Philharmonic/Kurt Masur. Beethoven: Symphony No. 1; Bruckner: Symphony No. 7.

5/16 Carnegie Hall. The MET Orchestra/Pierre Boulez. Bartók: The Wooden Prince (complete); Schoenberg: Erwartung.

5/17 Walter Reade Theater. Young Concert Artists Gala.