By Rachel Straus

Justin Peck’s “Year of the Rabbit” begins with a whirligig virtuoso solo by Ashley Bouder. The principal New York City Ballet dancer performs her multiple turns into off-kilter leaps with playful abandon. The total effect is that of “Road Runner” cartoon: Here comes Bouder. Beep Beep! The company that George Balanchine developed is known for moving speedily. But Justin Peck, a 25-year-old corps dancer who has now made three works for NYCB (this is his second), gets his dancers to move even faster than the company’s founding choreographer. About half way through Peck’s 2012 piece—to Michael P. Atkinson’s orchestration of Sufjan Stevens’ electronica album “Enjoy Your Rabbit” (2001)—one had to wonder what all the hurry was about.

Peck is the first choreographer who Ballet Master in Chief Peter Martins has supported that grew up firmly in the Internet age. While Christopher Wheeldon (age 39) and Alexei Ratmansky (age 44) surely have the latest gadgets, and Martins’ support, it is Peck’s fastidiously fast choreography that evokes the furrowed brow of our new century.

Back in the 1980s, it was Twyla Tharp who upped the ante on choreographic tempi. She taught aerobics as part of her company’s training. With “In the Upper Room” (1986), she featured dancers in tennis shoes and tracksuits, jogging up and down as though they were on a Stairmaster to heaven. But while Tharp’s “Upper Room” evokes the timelessness of Zen, via repetition of speedily performed choreographic leitmotifs, Peck’s interest in speed feels like young man’s game–with a smidgeon of ADD.

Though speed feels like the subject of “Year of the Rabbit,” it also concerns contemporary ballet and its values. In the center of the work, there is a romantic pas deux for the wonderfully expressive dancers Teresa Reichlen and Robert Fairchild. The pair appears to be questing for each other’s love: they dance in separate fiefdoms of the stage, created by boundaries formed out of dancers from the opposite sex. Yet as soon as Fairchild and Reichlen touch, they go their separate ways. The pas de deux’s erotic potency lies with the pair’s physical separation. Actual intimacy isn’t the point, just as Facebook concerns looking and commenting at friends and loved ones from the safety of one’s digital screen.

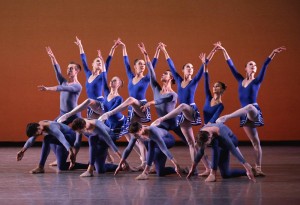

Peck’s musicality, in which he corresponds, sidles, and departs from Atkinson’s melodic lines, demonstrates that he is astute. His choreography for the corps is also notable. He continuously weaves the corps through six soloists’ dancing, thus blurring (and democratizing) the typical separation between leading and supporting dancers. All of this movement takes place place swiftly and efficiently, making “Rabbit” an indicator of our times.