By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 21, 2013

MUNICH — As dramaturgy, Calixto Bieito’s new staging here of Mussorgsky’s seven‑scene 1869 Boris Godunov (heard and seen yesterday, Feb. 20) runs into trouble almost immediately.

Set in present‑day Russia — identifiable by the up‑to‑date, thug‑police gear and the wall map in Boris’s Terem (Scene V) — it seems to want to cast Vladimir Putin as the boyar turned czar (actual reign: 1598–1605). Indeed, Putin’s face is first, front, and center among placards displayed in Scene I, as the crowd is bullied into endorsement of a leadership change.

But that would entail the Russian president dropping dead on the stage of Munich’s nice theater, an outcome for which not even Bieito — born in Old Castile, Spain — would have the cojones, to say nothing of Bavarian State Opera management’s likely concerns.

So the thing gets diluted. Putin’s face is promptly surrounded by placards for sundry other politicians, to wit: Cameron, Hollande, Monti, and Rajoy, supplemented by the peacefully removed from office Bush, Blair, Berlusconi, and Sarkozy; the current German chancellor and U.S. president apparently do not merit inclusion, though someone resembling Leon Panetta does. And Boris emerges as a fill‑in‑the‑blank oligarch, schemer and poison victim. His death (Scene VII) occurs at an oligarch get‑together attended — in a feeble try at framing the concept — by present‑day, multinational finance ministers. Boyar, you see, equals oligarch, equals business leader; finance ministers are there to cater.

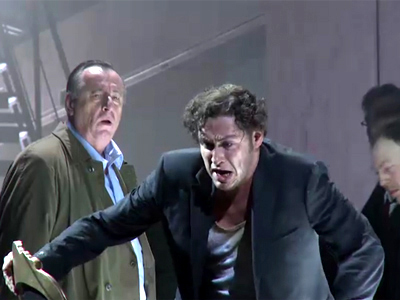

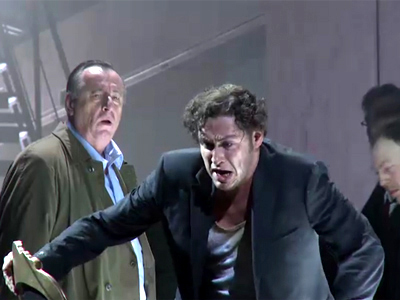

Still, Bieito shoots his interpretive load along the way with slices of supposed present‑day Russian life. People are shoved, choked and skull‑crushed by the police. Boris’s young daughter Xenia is a drunk. The Innkeeper (Scene IV) ruthlessly whips her own toddler while puffing a cigarette. The robbed Holy Fool is repeatedly stabbed by a little girl, and then shot in the head by her at close range under police cover.

Pimen the chronicler undoes history by ripping pages from a file. His student Grigory (a.k.a. False Dmitry I, czar in 1605–06) stabs a policeman, breaks the necks of the Nanny and Xenia, and suffocates Boris’s son Fyodor (historically czar in 1605). Boris’s own slow death, in context, doesn’t exactly ache in its poignancy.

For visual sustenance during the unbroken 135‑minute proceedings, we survey a cumbersome dark metallic unit shifting around the stage against an equally dark, smoky background. Technical staff here are proud of their mostly quiet hydraulics.

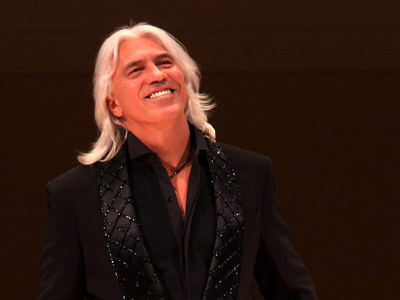

Last night’s performance (transmitted live on Mezzo TV) riveted attention through extraordinary singing. Alexander Tsymbalyuk’s stentorian bass voice in the title role brought eager expression to all lines of the anguished ruler. Secure from bottom to top, Tsymbalyuk sang with refined legato here, pointed declamation there. Now 36, this Ukrainian artist last year concluded a nine‑year affiliation with Staatsoper Hamburg; remember the not‑so‑easy name.

Veteran of the title role, and fellow Ukrainian, Anatoli Kotcherga (65) invested Bieito’s un‑chronicler with power, eloquence and welcome stature. Another sometime Boris, Vladimir Matorin (64) from Moscow, boomed with full‑voiced, undaunted lyricism as Varlaam, effective well beyond So It Was In the City of Kazan.

St Petersburg tenor Sergei Skorokhodov introduced a clarion, unstrained Grigory. Gerhard Siegel floated attractive tones in the oily duties of Basil Shuisky (future czar Basil IV, 1606–10), presenting the character as a credible advisor more than as a scorned stereotype. Company member Okka von der Damerau lent her vivid and plush mezzo to the hard‑put‑upon, abusive Innkeeper, and 23‑year company member Kevin Conners of East Rochester, NY, bellyached musically as the Holy Fool.

Advance hopes that Kent Nagano might bring some sweep, flair or insight to Mussorgsky’s graphic score — his last premiere as Bavarian State Opera Generalmusikdirektor — soon receded. His approach was plain, without feel for the Russian phrase. If he grasped the problems of balance caused by Mussorgsky’s intermittent misjudgment of orchestral weight, in this third performance of the run, he made no audible compensation for them. As usual he paced the music fittingly and coordinated well. Wind ensemble fell below par for the Bavarian State Orchestra; the chorus sang in unclear Russian, with greater musical discipline than usual. Disenchanted by Bieito’s whopping liberties with the colorful, pageant‑endowed story, but enthralled by the singing, the crowd applauded lightly.

Still image from video © Bayerische Staatsoper

Related posts:

Petrenko’s Sharper Boris

Manon, Let’s Go

Verdi’s Lady Netrebko

Thielemann’s Rosenkavalier

Petrenko’s Rosenkavalier