By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 22, 2017

MUNICH — Bavarian State Opera had a delicate problem. It was selling too many tickets online, more with each passing season. Its system, powered by CTS Eventim, was so robust and so fast that little was left to sell via phone or in person minutes after the 10 a.m. start time on heavy-demand days, causing embarrassment and a sense of unfairness inside its bricks-and-mortar box office, the Tageskasse, off chic Maximilianstraße.

No longer. This season, Germany’s busiest, richest, starriest and arguably best-managed opera company has a cure, one to make any Luddite proud. It does not smash the machines exactly. It instead decries the good system behind them and handicaps the online buyers who use them — seriously, unpredictably, before breakfast. BStO seats below €100 when Anja Harteros or Jonas Kaufmann sing are now all but inaccessible online.

“CTS Eventim’s system sometimes was not up for the amount of people trying to get tickets,” the company claimed in a late-January statement, and buying was “a bit of a lottery.” The system “would throw you out of the purchase process before ending it, which was acceptable neither for the Staatsoper nor for our audience.” Imagine. Computers that sell 100 million tickets annually for 180,000 events get the jitters handling Anja or Jonas.

These flaws and a desire “to make the system more stable,” BStO’s story goes, led to its decision last fall to handicap online buying on certain mornings in 2016–17. How? A delay is “activated” when events in heavy demand go on sale, postponing the moment the buyer “gets access” to the online box office, called in German the Webshop (or occasionally Onlineshop). Phone and in-person selling, meanwhile, proceed as usual from the 10 a.m. start time.

Understandably the opera company has never announced the handicapping, and sources familiar with the Tageskasse scene say CTS Eventim’s system had nothing to do with the decision. The real motive, according to these sources, is to try to replicate online the speed of the physical line (queue) at the Tageskasse following years of grumbling from people who buy that way, and from staff too. A tug-of-war between Internet users and the bricks-and-mortar crowd has accordingly shifted in favor of the latter.

Out-of-town buyers are the worst hit, having fewer routes to tickets. Bavarians resident outside their capital city — it is the “state” opera after all — and fans of the renowned company as far away as East Asia and North America greatly rely on the Webshop.

The disadvantage is not new at BStO. Indeed the artificial online delays effectively bring to the main season the same narrow price availability for out-of-towners they have long experienced with BStO’s 142-year-old summer Munich Opera Festival. Tickets for the festival are first sold in snowy January in person only, and the lower four of eight price categories — roughly, seats below €100 for major performances — sell out this way when the biggest stars are scheduled, months before online ticketing starts.

Countless customers were surprised by the handicap on Jan. 12, 14, 18, 22, 30 and Feb. 2 while trying to buy tickets for Philipp Stölzl’s new production of Andrea Chénier, due March 12 and starring — gosh — both Harteros and Kaufmann. All performances were affected on those selling mornings, corresponding to BStO’s two-month lead time.

Surprised, and confused actually. The handicap throws up two screens in place of the Webshop. First, a countdown page, labeled with the quaint metaphor “waiting room” to dupe people into thinking the system is too burdened to process their order. This assigns a wait number, which ironically turns out to be far from “stable.” Then comes a standby page, for buyers whose number has dropped to 0 (zero) before the Webshop opens, i.e. before 10 a.m. — a strange situation, one might think, but the only one with potential to yield broad ticket choice.

Not-so-hypothetical scenarios:

| |

A in Augsburg

Unaware of the handicap, she logs on at 9:55 a.m. She faces not her expected Webshop but the countdown page. (She would be there regardless of what event and date she is pursuing. The whole operation is impacted that morning because one heavy-demand performance is going on sale.)

She has of course no idea when the handicap was activated. (The answer could be 6 a.m., about when a physical line might start outside the Tageskasse.) But she is less troubled than buyers who may have purposefully stopped work in Tokyo or climbed out of bed in Boston.

She sees 29 lines of precise instructions auf Deutsch, unless she has opted for English screens, in which case she sees a remarkably compressed version of just five lines. (The complete English is here.) Key instruction: “Do not refresh.” Below, she reads her wait number: a high one, 400. Her chances are nil, but she doesn’t know this. She ties herself up for an hour before learning. |

| |

N in Nuremberg

Logs on at 5:55 a.m. She is too early and goes straight into the normally functioning Webshop. She assumes she can just wait there until 10 a.m. But no. She must refresh the screen every twelve minutes or be disabled for inactivity. No instructions say this because the system was in normal mode when she entered. (To see them, she would have had to arrive via the countdown page and witness her wait number drop to 0 before 10 a.m.)

When she casually returns to the screen at 9:30 a.m., she discovers the Webshop inactive for her. She reloads. Now she is on the countdown page with number 200. Again no chance. |

| |

R in Regensburg

Fares better. He logs on at 6:15 a.m., apparently just after the handicap was activated. He lands on the countdown page with number 10. Like A, he is told not to refresh. He obeys. Later, but before 10 a.m., his number drops to 9, then 7. He wonders how this could be. No orders are being processed. (Possible answer: people on the standby page are failing to refresh and losing their place.)

But for him to succeed, his number must drop to 0 by 10 a.m. Otherwise, whether he’s at 400 or 4, he will be stuck on the countdown page during the crucial initial selling minutes.

Luckily he does drop to 0. He is moved to the standby page, a promising but precarious place. There he sees the instruction to refresh that N missed. He must do this every twelve minutes until 10 a.m. If he has arrived on the standby page early, say at 7:15 a.m., he will be doing a lot of refreshing. Should he fail — just once — he will find himself back on the countdown page holding a high number. (Anja and Jonas never wanted it that way.)

When the hour rolls around and the handicap ends, he must be ready, as in the past, to point and click with decisiveness and accuracy. His seats are secure only when they appear in his Einkaufswagen, the shopping cart. |

A, N, and R may be imagined. The following numbers are real, recorded during the Jan. 18 handicap on Andrea Chénier ticketing in checks using two browsers and two connections:

Logging on at 10:24 a.m., a wait number of 688 with 170 seats left to sell. Three minutes later, wait number 346 with 130 seat left. At 10:43 a.m., number 179 with 38 seats. At 10:54 a.m., number 40 with 19 seats. After another five minutes, access to the Webshop with 4 seats shown as available. By 11:04 a.m., 2 seats left but neither one of them moveable into the shopping cart. At 11:07 a.m., sold out, Ausverkauft. Despite this, a new buyer could log on at 11:10 a.m. and receive wait number 382, which would drop to 0 six minutes later and lead to an empty Webshop.

Bavarian State Opera should end this nonsense. The company is damaging its reputation and working against its own carefully evolved ticket structure and sales procedures, designed to draw people of all income levels from a broad geography.

Those procedures sell tickets three ways: subscription; single-event by written order; and single-event by immediate fulfillment. The latter two are processed on a staggered basis according to performance date. Written orders (traditional mail, fax, email) are worked three months out. Immediate-fulfillment sales (online, phone, physical presence in the Tageskasse) begin two months out.

Each single-event method draws on fixed set-asides, or Kontingente, of seats in the 2,100-seat National Theater. These are broken down across BStO’s eight price categories and to within specific seating blocks, to as few as two seats, allowing near-total price and seat choice for each method. Quite sophisticated. And really quite fair, at least in the case of written orders. Even without handicapping, though, buyers outside Munich have less access to the immediate-fulfillment set-asides: getting to the Tageskasse may not be possible, and phoning is hard when there is heavy demand. Naturally they depend on the Webshop — and their hot connections, firm wrists, pinched fingertips and nanosecond nerves.

CTS Eventim, far from warranting criticism, could be held up as a most capable and user-friendly ticketer. Certainly its system offers an easier buyer interface, more precise seat sectioning, and lower fees, than that of the larcenous near-monopoly Stateside.

Instead of blaming its vendor, the opera company needs to go back to the future and solve its delicate Tageskasse problem with rigor and honesty. This means two things: adjustments to the Kontingente to reasonably protect in-person buyers; and an announcement of the change. Any tactic resulting in Internet screens that mislead buyers and waste their time, or too weird to spell out in a news release, is a bad one.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Staatsoper Imposes Queue-it

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Antonini Works Alcina’s Magic

Portraits For a Theater

Staatsoper Objects to Report

Tags:Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Commentary, CTS Eventim, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, News

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Sunday, August 7th, 2016

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: August 7, 2016

MUNICH — Two evenings after an “Allahu Akbar” eruption here cost nine mostly teenage, mostly Muslim, lives, it felt perverse to indulge in 280-year-old French escapism stretching to Turkey, Peru, Iran and the future United States.

But there we were July 24 in the Prinz-Regenten-Theater for Bavarian State Opera business-as-usual, a festival yet, and Rameau’s four-entrée Les Indes galantes as imagined by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, the Belgian choreographer with stage-director pretensions.

And safer we were, too, than at a smaller music festival 110 miles away near Nuremberg, the outdoor Ansbach Open, where a Syrian refugee denied asylum in this country was preparing to explode his metal-piece-filled backpack among two thousand listeners. (As luck would have it, Germany’s first suicide bomber killed only himself when he detonated only his detonator and did so outside the festival’s gates, not having known in advance he would need a ticket.)

Before departing for Turkey, the opéra-ballet states its premise by means of a prologue: European lovers pressed to exchange Goddess Hébé’s doux instants (sweet moments) for Goddess Bellone’s gloire des combats can count on intercession from a third god, Amour, as they “traverse the vastest seas” in military service.

This plays out with amusing dramatic variance* in the four locales to music of beguiling harmony and bold instrumental color, in airs, vocal ensembles, choruses and dances. The U.S. entrée concludes with the Dance of the Great Peace Pipe (penned after Agapit Chicagou’s 1725 Paris visit), minuets, a gavotte, and a most charming chaconne.

If you kept your eyes closed, the performance was a treat. Opening them invited confusion, or worse, despite Cherkaoui’s fresh dance moves, tirelessly executed by his Antwerp-based Compagnie Eastman.

Ivor Bolton and the Münchner Festspiel-Orchester, an elite Baroque pick-up band, served Rameau with verve and expressive breadth, ripe string sound and fabulous wind playing. The Balthasar-Neumann-Chor from Freiburg managed its musical challenges neatly, in opaque French.

The score’s 17 roles went to ten generally stylish soloists. Lisette Oropesa proved a graceful musician in the lyric soprano duties of Hébé and Zima. Anna Prohaska, as Phani and Fatime, stopped the show with a divinely phrased Viens, Hymen, viens m’unir. Light tenor Cyril Auvity sang artfully as Valère and Tacmas, while John Moore’s baritone lent a golden timbre to the sauvage Adario. Reveling grandly in the music’s depths were basses François Lis (Huascar and Alvar) and Tareq Nazmi (Osman and Ali).

But soprano Ana Quintans encountered pitch problems as Amour and Zaïre; Elsa Benoit, the Émilie, seemed squeezed by Rameau’s nimble turns; Mathias Vidal pushed harshly for volume in the tenor roles of Carlos and Damon; and bass Goran Jurić, in drag as Bellone, muddied her vital rousing words.

As for the staging, new on this night, conceit and a ruinous idea got the better of Cherkaoui (and BStO managers, who should have intervened if they care about Baroque opera as they profess): he would thread together the prologue and entrées into one dramatic unit. Characters would appear in each other’s sections, mute. Opéra-ballet form be damned.

In place of exotic lands (requiring exotic sets and costumes), the viewer would journey from schoolroom to museum gallery to church to flower shop, to no place, to some closed border crossing. The spectacle of Peru’s Adoration du Soleil, for instance, would unfold in the church. Woven throughout, clumsily, would be tastes of the plight of Europe’s present refugees, and Europeans’ poor hospitality. Count the ironies.

[*In Turkey a melodrama, as the shipwrecked lovers’ fate turns on Osman’s magnanimity (Le turc généreux). In Peru a tragedy, as the couple’s freedom results from Huascar’s molten-lava death (Les incas du Pérou). In Iran a bucolic, as two pairs of lovers ascertain their feelings through disguise and espial (Les fleurs, original version of Aug. 23, 1735). In the U.S. a comedy, as noble savage Zima flirts with and mocks two European colonists, reversing the pattern, before homing in on loving native Adario (Les sauvages).]

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Portraits For a Theater

Nitrates In the Canapés

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Blacher Channels Maupassant

On Wenlock Edge with MPhil

Tags:Ana Quintans, Anna Prohaska, Balthasar-Neumann-Chor, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Compagnie Eastman, Cyril Auvity, Elsa Benoit, François Lis, Goran Jurić, Ivor Bolton, John Moore, Kritik, Les Indes galantes, Lisette Oropesa, Mathias Vidal, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, Prinz-Regenten-Theater, Rameau, Review, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Tareq Nazmi

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Sunday, July 17th, 2016

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: July 17, 2016

MUNICH — When Anja Harteros was singing her first Toscas three seasons ago, it was clear she had the vocal resources for the role, and the Mediterranean temperament. Even so, the portrayal didn’t quite compute.

Enter Bryn Terfel, a Scarpia to rattle the aloofest, longest-legged of prima donnas. And Jonas Kaufmann, trusted stage buddy, sweet Cavaradossi. Now the diva’s doubt, fear, passion and rage turn on the instant, her slashing knife grip extending a ferrous will.

Harteros fairly lived the part July 1 here at the National Theater, teamed as she must have wanted and apparently undeterred by Luc Bondy’s clunky 2009 stage conception. Warm chest tones and creamy highs, floated or hurled, came into thrilling dramatic focus this time around. Illica and Giacosa’s words made inexorable sense, the Attavanti canvas and Terfel’s guts sure targets.

The tenor, too, had a great night: astutely colored phrases, gleaming top notes, a clarion but unexaggerated Vittoria! For once, E lucevan le stelle emerged as spontaneous thought, always in Kaufmann’s wonderfully lucid Italian.

If the mighty Welshman sounded a smidgen less opulent of voice than in previous Munich Scarpias, his characterization was as potent as ever, and his savoring of Puccini’s lines most enjoyable.

The snag, alas, was Kirill Petrenko’s conducting. Forceful and weighty, it never felt rooted in the language it was supposedly driving. Still, a terrific night for the Munich Opera Festival, and nowhere more refined than during Io de’ sospiri as sung by the Tölzer Knabenchor’s uncredited soloist.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Manon, Let’s Go

Tonhalle Lights Up the Beyond

Busy Week

Time for Schwetzingen

Schultheiß Savors the Dvořák

Tags:Anja Harteros, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bondy, Giacomo Puccini, Kaufmann, Kirill Petrenko, Kritik, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Review, Terfel, Tölzer Knabenchor, Tosca

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Tuesday, May 17th, 2016

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: May 17, 2016

MUNICH — Beckmesser blew his brains out at the end of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg last night here in the Nationaltheater. That was after first aiming his gun at the back of the head of Sachs, and after a graphically brutal beating by David and bat-wielding apprentices had left him in a wheelchair — a predicament from which he had miraculously recovered, back onto his feet, within the few hours separating Johannisnacht and Johannisfest. Sachs, for his part, never saw the gun; he was sitting moping because Stolzing had ignored his Verachtet mir die Meister nicht, had declined to honor German art or the masters safeguarding it, and had simply walked out with Pogner’s prized daughter.

Whether Beckmesser’s character is of the suicidal type is a fair, though in context minor, question. Stage director David Bösch’s new production for Bavarian State Opera offers an altogether transformed view of Wagner’s erstwhile comedy, funded by the same hardworking Bavarian people who brought you the first, on June 21, 1868, when Hans von Bülow occupied GMD Kirill Petrenko’s podium.

Swiss-trained Bösch explores the role art can play in society by winding the clock in the opposite direction from the composer. Instead of reaching back three centuries to show the art-guild tradition at its liveliest, when Nuremberg prospered, he forwards us to a faceless town that has seen better days, where the institution feted by Wagner is in yet more jeopardy than when the score was written and where the masters in their trades suffer the effects of debilitating, distant economic forces. Somewhat outside these problems is the presumably flush Stolzing, but even he cannot invigorate through his candidacy a guild whose masters find it easier to delude themselves than honestly confront demise. Sachs’s Wahnmonolog fits right in. Not much else does.

The idea of collective depression finds little use for such musical-dramatic particulars as the scent of the Flieder (lilac) or the shade of the Linde (basswood). Bösch has to invert the humor in, for instance, the Nachtwächter’s round and Sachs’s gift to Beckmesser. He defies Wagner’s time-of-day and lighting directives. Indeed, clashes with the composer create an uneasy mix of narrative, pomp, violence and slapstick (song-trial errors marked via shocks to the applicant in an electric chair; a town-clerk serenade from atop a scissor-lift, constantly raised and lowered by the cobbler).

But Bösch’s own visual-stylistic trademarks are firmly in place, reminding us of his spacy, zoned-out previous work for this company: L’elisir d’amore (2009), Mitridate, rè di Ponto (2011), and, his touching flower-power effort, La favola d’Orfeo (2014). Neatly arranged decay, locally lit props, black limbo backgrounds, a funky insouciance to the stage action: these are some.

The Bavarian State Opera Chorus sang magnificently for this premiere, achieving levels of expressive detail and shading it reserves for its obsessive GMD; Sören Eckhoff did the coaching. Sara Jakubiak from Bay City, MI, made a welcome debut as Eva, acting well and producing girlish tones in mostly clear German. Benjamin Bruns coped sweetly with the boisterous lyric challenges of David. Jonas Kaufmann added the quality of heroic delivery to the youthful ardor and Lied skills evident in his Scottish Stolzing of long ago. Wolfgang Koch, vocally opulent, looked sloppy as Sachs but conveyed enlightenment anyway. He projected his words impeccably and never forced for volume. Markus Eiche’s musically ideal Beckmesser deserved and received the loudest applause, after tough toiling in Bösch’s action. Christof Fischesser intoned nobly and richly through Pogner’s wide vocal range, while the Nachtwächter’s chant seemed all too short as securely phrased by Tareq Nazmi.

Petrenko drew playing of color and sparkle from his Bavarian State Orchestra, favoring momentum (78’ 58’ 70’ 42’) over reflection but pointing the rhythms with ceaseless energy and emphasis, much to the opera’s advantage. Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg will be streamed as video over the Internet at 5 p.m., Munich time, on July 31, 2016, under sponsorship from Linde.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

See-Through Lulu

Time for Schwetzingen

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

Mariotti North of the Alps

MKO Powers Up

Tags:Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerischer Staatsopernchor, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Benjamin Bruns, Christof Fischesser, David Bösch, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Kaufmann, Kirill Petrenko, Kritik, Markus Eiche, München, Munich, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Review, Sara Jakubiak, Sören Eckhoff, Tareq Nazmi, Wolfgang Koch

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Friday, April 22nd, 2016

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: April 22, 2016

MUNICH — Vasily Petrenko’s debut at Bavarian State Opera this weekend prompts a glance at two Russian-born, modestly profiled conductors who have built distinct careers in Western Europe while sharing a last name. The guest from Liverpool will lead Boris Godunov, last revived two years ago by company Generalmusikdirektor Kirill Petrenko.

Inviting Vasily to work in Kirill’s house was sweet, ingenuous. After all, the two Petrenkos are what trademark attorneys call “confusingly similar” marks, a factor that doesn’t vanish just because real names are involved, or because it’s the arts. Are artists products? Their work is, notwithstanding the distance from commerce.

The Petrenkos are not of course the first conductor-brands to overlap, but unlike the Kleibers or Järvis, Abbados or Jurowskis, no disparity of talent or generation neatly separates them. Then, inescapably, there is the matter of dilution: a “Toscanini” needs no specifier.

As it happens, agents have promoted the Petrenkos as if with accidental care over geography. Although both men have enjoyed positive forays Stateside, awareness of them in Europe diverges. For a full decade, Vasily has been the “Petrenko” of reference in Britain. Kirill has been “Petrenko” in Germany.

Kirill has had such minimal renown in Britain, in fact, that retired Bavarian State Opera chief Peter Jonas last summer on Slipped Disc could report the following about the Bavarian State Orchestra’s upcoming European tour: “The [orchestra’s] committee and their management offered themselves to the [BBC] Proms for 2016 … and were sent away with the exclamation, ‘Oh no … . Kirill Petrenko? We do not really know about him over here.’ … The tour will happen all over Europe but without London.” Indeed it will.

In the meantime, Calisto Bieito’s staging of Boris Godunov gets a three-night revival April 23 to 29 with a strong cast: Sergei Skorokhodov’s pretender, Ain Anger’s chronicler and Alexander Tsymbalyuk’s riveting Boris. How will Vasily grapple with the (1869) score? Opera featured prominently in his career only at the start.

| |

Kirill |

Vasily |

| |

Кирилл Гарриевич Петренко |

Василий Эдуардович Петренко |

| born |

Feb. 11, 1972, in Omsk — 44 |

July 7, 1976, in St Petersburg — 39 |

| hair |

auburn, curly |

blond, straight |

| eyes |

brown |

gray |

| height |

5 feet 3 inches |

6 feet 5 inches |

| weight (est.) |

145 lbs., trim |

180 lbs., trim |

| training |

Vorarlberg State Conservatory in Feldkirch |

St Petersburg Conservatory |

| influences |

Bychkov, Chung, Eötvös, Lajovic |

Jansons, Martynov, Salonen, Temirkanov |

| early job |

Kapellmeister, Volksoper, Vienna, 1997–99 |

Resident Conductor, Mikhailovsky Theater, St Petersburg, 1994–97 |

| now |

Generalmusikdirektor, Bavarian State Opera |

Sjefdirigent, Oslo Philharmonic; Chief Conductor, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic |

| lives in |

refused to disclose |

Birkenhead Park, Merseyside |

| companionship |

rumored to have platonically dated soprano Anja Kampe |

married to Evgenia Chernysheva, choral conductor and music tutor; Sasha (11), Anna (2) |

| faith |

private |

Russian Orthodox |

| favorite team |

refused to disclose |

Zenit St Petersburg (soccer) |

| diplomacy |

on Ukraine: “I observe the conditions there with great concern. What is happening there is anything but normal. A political solution [is needed] that does not impinge on Ukraine’s sovereignty.” Speaking at the National Theater, March 6, 2014 |

on women conductors: “[Orchestras] react better when they have a man in front of them … . A cute girl on a podium means that musicians think about other things.” Quoted in The Guardian, Sept. 2, 2013 |

| humor |

while working with Miroslav Srnka on his 2015 opera South Pole: “If the composer is dead, you’d like to ask him questions, but you can’t. If [he] is alive, you can ask him questions, but sometimes you’d prefer he would be already dead.” Reported by Slipped Disc, Jan. 18, 2016 |

while attempting damage control: “We were saying that because a woman conductor is still quite a rarity … , their appearance [on] the podium, because of the historical background, always has some emotions reflected in the orchestra.” Quoted in The Telegraph, May 8, 2014 |

| distinctions |

|

Honorary Scouser

Echo Klassik Award |

| achievement |

survived nine cycles conducting Der Ring des Nibelungen at Bayreuth |

completed a Shostakovich cycle for Naxos |

| strengths |

Mussorgsky, Strauss, Elgar, Scriabin, Berg |

Shostakovich |

| weakness |

Donizetti (and probably Verdi) |

|

| what John von Rhein said |

“Solidity of technique, quality of leadership, depth of musical ideas and ability to strike a firm rapport with [Chicago Symphony Orchestra] members … [determine whether a conductor] stands or falls … . By all these standards [he] sent the needle off the symphonic Richter scale at his first concert.” March 2012 CSO debut |

“His beat is clear and he has a knack for focusing on the essentials, his long fingers fluttering in a highly expressive manner … . He inspired the [Chicago Symphony Orchestra] to go well beyond its normal megawatt virtuosity, and this made for a blistering account of the Shostakovich [Tenth].” Dec. 2012 CSO debut |

| CDs |

|

|

| |

Suk’s Asrael Symphony and Pfitzner’s opera Palestrina for CPO and Oehms |

Rachmaninoff’s First Symphony and the Shostakovich Cello Concertos with Truls Mørk for Warner and Ondine |

| career trajectory |

modest inclination |

less modest inclination |

| compass setting |

north, tardily |

south, east, west |

Placing the two Petrenkos side by side here, like baseball cards, meant compiling at least some personal facts along with the musical. So, three questions went to the conductors’ handlers. How tall is he? Where does he live (part of town)? What’s his favorite sports team?

This proved awkward, however, especially on one side, and hitherto-cordial staffers turned as cool as, well, trademark attorneys. Vasily’s people cooperated with partial answers. Kirill’s, deep inside Bavarian State Opera, stonewalled: “Mr. Petrenko generally does not wish to answer any personal questions.”

As it turned out, Vasily was on record with full answers over the years to all three questions for various media outlets. The man is an open book. This left Kirill’s side with unflattering holes. But the opera company’s hands were tied. Apparently under instructions from the artist, nobody could even confirm he lives in Munich (where he has drawn a paycheck for 30 months already). And he may not.

Bavarian State Opera: “What’s not to understand about ‘Mr. Petrenko does not wish to answer any personal questions’? Who puts out the rule that a conductor … does have to comprehend or be willing to be part of public relations? … So, in fact, we do not want to convey anything to anybody. This is the ‘line to be drawn’ from our side.”

Mention of Vasily went over badly. BStO: “What kind of idea is it anyways to compare two artists because they share the same last name?” Prepared descriptors accompanied the rhetoric: “ridiculous” and a “game.” How not to kill a story.

Shown the data for the above table, the opera company took to sarcasm: “Yes, sure, [inventing] height and weight [measurements] is of course totally acceptable.” But Kirill’s height had become public half a year ago* at ARD broadcaster Deutsche Welle. BStO did not either know this or wish to share the knowledge. Its hapless official scanning DW: “Oh, it’s on the Internet! It’s gotta be true!”

[*Earlier actually: Lucas Wiegelmann included it in an excellent 2014 discussion for Die Welt.]

Photos © Bayerische Staatsoper (Kirill Petrenko), Royal Liverpool Philharmonic (Vasily Petrenko)

Related posts:

Petrenko’s Sharper Boris

Portraits For a Theater

Bieito Hijacks Boris

Nazi Document Center Opens

Petrenko to Extend in Munich

Tags:Ain Anger, Alexander Tsymbalyuk, Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Boris Godunov, Commentary, Kirill Petrenko, München, Munich, Mussorgsky, News, Oslo Philharmonic, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Sergei Skorokhodov, Vasily Petrenko

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Sunday, March 13th, 2016

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: March 13, 2016

MUNICH — Some contracts come with strings attached, others with husbands. In a remarkable set of coincident artistic priorities for company boss Nikolaus Bachler — or a broad capitulation — Bavarian State Opera’s 2016–17 season, announced today, features no fewer than six divas in performance with their husbands. Edita Gruberová, Elīna Garanča and Kristine Opolais will star in Roberto Devereux, La Favorite and Rusalka while their other halves conduct. Diana Damrau, Anna Netrebko and Aleksandra Kurzak will headline Lucia di Lammermoor, Macbeth and La Juive while alongside them their spouses sing. In another family tie, Vladimir Jurowski has apparently been allowed to abandon the new Ognenny angel he led (electrically) this season in favor of … his dad. Small wonder 2016–17 is dubbed “Was folgt”: What follows.

Photos © Wiener Staatsoper (Elīna Garanča), Opernhaus Zürich (Anna Netrebko), Bill Cooper for the Royal Opera House (Kristine Opolais), Catherine Ashmore for the ROH (Aleksandra Kurzak, Diana Damrau), Wilfried Hösl (Edita Gruberová)

Related posts:

Kaufmann, Wife Separate

Antonini Works Alcina’s Magic

Manon, Let’s Go

Poulenc Heirs v. Staatsoper

Concert Hall Design Chosen

Tags:Aleksandra Kurzak, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Commentary, Diana Damrau, Edita Gruberová, Garanča, Kristine Opolais, La Juive, Lucia di Lammermoor, Macbeth, München, Munich, Netrebko, News, Nikolaus Bachler, Ognenny angel, Roberto Devereux, Vladimir Jurowski

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Sunday, January 31st, 2016

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: January 31, 2016

MUNICH — Three years ago Bavarian State Opera’s yearly Silvester performances of Die Fledermaus came to a sudden, poorly excused halt. Never mind that they were a global signature of the company; Carlos Kleiber famously led ten of them. As substitutes, the powers-that-be provided La traviata (Verdi was 200) and then, weirdly, L’elisir d’amore. But last month the bat returned, courtesy of GMD Kirill Petrenko, who, it turns out, is as much a fan as Kleiber and a tautly disciplined but supple musical advocate. Indeed he conducted gleefully Dec. 31 and Jan. 4 yet with his customary, at times martial, intensity, the carotid arteries alarmingly discernible — which did not preclude ballerina-like poses, hands high, fingers pointed together, for stylish delays in Johann Strauss’s three-four time. The orchestra sizzled. The chorus sang with astonishing precision and expressive warmth, not least for Brüderlein, Brüderlein und Schwesterlein. Oozing charm and impeccable in their comic timing as the Eisensteins were Marlis Petersen and Bo Skovhus. She sang, also danced, a seductive table-top Klänge der Heimat, ending on the eighth-note high D, as written, although less than forte. Anna Prohaska brought moxie and what may have been a fine Lower Austrian drawl, not much volume, as the “Unschuld vom Lande.” Edgaras Montvidas contributed an ardent, grainy-sounding Alfred, Michael Nagy a mellifluous Falke, mezzo Michaela Selinger a game but too-bright-sounding Orlofsky; her party guest, Thomas Hampson, in town to prepare for Miroslav Srnka’s costly new opera South Pole, interpolated a lavish Auch ich war einst ein feiner Csárdáskavalier … Komm, Zigan, spiel mir was vor. Missing, alas, was the magnetic Alfred Kuhn, long a definitive, droll Gefängnisdirektor Frank here (also Antonio the gardener and Benoît the landlord); in context, Christian Rieger looked and sounded awkwardly robust. Andreas Weirich’s rethinking of the old Leander Haußmann production worked best in Acts I and II. The cramped jail action sputtered, and Viennese actor Cornelius Obonya, a Salzburg Jedermann, went on too long as Frosch; he will be replaced this coming New Year’s Eve by a Bavarian.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Petrenko’s Rosenkavalier

Verdi’s Lady Netrebko

See-Through Lulu

Petrenko’s Sharper Boris

Manon, Let’s Go

Tags:Andreas Weirich, Anna Prohaska, Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerischer Staatsopernchor, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Bo Skovhus, Carlos Kleiber, Christian Rieger, Cornelius Obonya, Die Fledermaus, Edgaras Montvidas, Johann Strauß, Kirill Petrenko, Marlis Petersen, Michael Nagy, Michaela Selinger, München, Munich, Review, Thomas Hampson

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Thursday, January 7th, 2016

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: January 7, 2016

MUNICH — Bavarian State Opera will defy the heirs of Francis Poulenc and proceed with revival performances of its literally explosive staging of Dialogues des Carmélites later this month, the company said today.

The 2010 production by Dmitri Tcherniakov departs from the scheme of the composer and the source novelist, Georges Bernanos, in several ways and has been described by the heirs as a “trahison.” Not the least of its transgressions is a substitution in the climactic scene: a deadly gas blast and one self-sacrifice (by Blanche) replace the serial guillotining of the titular nuns laid out graphically in the music.

In a Dec. 23 letter to the Munich company, the heirs demanded that the “rights-infringing staging of the work (ihren Rechten verletzenden Aufführung des Werkes)” be put to “no further use.”

But a slow-won French court victory for the heirs last October constrained only BelAir Classiques and Mezzo TV from, respectively, selling DVDs of the production and screening it. The estates of both Poulenc and Bernanos had begun legal proceedings in October 2012, perhaps not aware of the nature of Tcherniakov’s efforts until BelAir’s DVD release that year. The last onstage revival came, by coincidence, the same month.

Poulenc’s 1956 opera is evidently less tightly controlled, or protected, by his heirs than is, for example, Gershwin’s 21-years-older Porgy and Bess by the American composer’s estate.

In justifying the resolve to proceed, Bavarian State Opera’s Geschäftsführender Direktor Roland Schwab said: “In the context of an earnest grappling with the work, the stage direction must have the freedom to deviate from history. Thus the work is not disfigured, but rather its ideas are depicted from today’s viewpoint.”

The company also noted it had made no alteration to libretto or score. This despite the stripping out of all Christian reference as well as the guillotining from the stage action. BStO Intendant Nikolaus Bachler is a firm, one might say notorious, defender of unfettered Regietheater.

Not only will the show go on, but Bavarian State Opera is supporting BelAir Classiques and Mezzo TV in their appeal of the October court decision, the company said.

Scheduled to sing the opera Jan. 23 to Feb. 1 are Christiane Karg as Blanche, Anna Christy as Constance, Anne Schwanewilms as Lidoine and Stanislas de Barbeyrac as the Chevalier. Susanne Resmark and Sylvie Brunet reprise their roles as Marie and de Croissy on the banned 2010 DVD. Bertrand de Billy conducts.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Poulenc DVD Back On Market

Thielemann’s Rosenkavalier

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

Tonhalle Lights Up the Beyond

Antonini Works Alcina’s Magic

Tags:Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, BelAir Classiques, Commentary, Dialogues des Carmélites, Dmitri Tcherniakov, Mezzo TV, München, Munich, News, Nikolaus Bachler, Poulenc, Roland Schwab

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Wednesday, September 30th, 2015

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 30, 2015

MUNICH — Bavarian State Opera’s irredeemably banal 2009 Aida has been spiffed up and its awkward action scheme apparently restudied for a fall run here. Even so, the honors at Monday’s performance (Sept. 28) belonged firmly with the musicians, instrumental and vocal. Mannheim-based conductor Dan Ettinger exerted a Karajan-like grip, stirring Verdi’s music from the bottom up, parading its rhythmic strengths, brashly stressing percussive detail, and inevitably drawing attention to himself. Which is not to say he drowned everyone out: he accompanied attentively and savored well-rehearsed balances. The Bavarian State Orchestra cooperated gamely; the Bavarian State Opera Chorus sang with rare refinement in clear Italian. Krassimira Stoyanova acted so credibly and poignantly through her essentially lyric voice that nobody would have guessed she is new to this opera. Her sound was pure and unforced, her phrasing properly noble for the title role. Amneris suits Anna Smirnova better than did Eboli here four seasons ago, but her communicative singing in Acts III and IV followed a numb, robotic portrayal before the Pause. Jonas Kaufmann proved he can sing Radamès outside of studio conditions, and thrillingly, starting with an exquisitely shaped Act I Romanza and progressing to generous, imaginative ensemble work. Franco Vassallo’s warm and unstrained Amonasro, Ain Anger’s formidable Ramfis, and Marco Spotti’s eloquent Rè d’Egitto completed a straight-A cast of principals.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Verdi’s Lady Netrebko

Nézet-Séguin: Hit, Miss

Chung to Conduct for Trump

Christie Revisits Médée

Time for Schwetzingen

Tags:Aida, Ain Anger, Anna Smirnova, Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerischer Staatsopernchor, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Dan Ettinger, Franco Vassallo, Giuseppe Verdi, Kaufmann, Krassimira Stoyanova, Kritik, Marco Spotti, München, Munich, Review

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Staatsoper Favors Local Fans

Wednesday, February 22nd, 2017By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 22, 2017

MUNICH — Bavarian State Opera had a delicate problem. It was selling too many tickets online, more with each passing season. Its system, powered by CTS Eventim, was so robust and so fast that little was left to sell via phone or in person minutes after the 10 a.m. start time on heavy-demand days, causing embarrassment and a sense of unfairness inside its bricks-and-mortar box office, the Tageskasse, off chic Maximilianstraße.

No longer. This season, Germany’s busiest, richest, starriest and arguably best-managed opera company has a cure, one to make any Luddite proud. It does not smash the machines exactly. It instead decries the good system behind them and handicaps the online buyers who use them — seriously, unpredictably, before breakfast. BStO seats below €100 when Anja Harteros or Jonas Kaufmann sing are now all but inaccessible online.

“CTS Eventim’s system sometimes was not up for the amount of people trying to get tickets,” the company claimed in a late-January statement, and buying was “a bit of a lottery.” The system “would throw you out of the purchase process before ending it, which was acceptable neither for the Staatsoper nor for our audience.” Imagine. Computers that sell 100 million tickets annually for 180,000 events get the jitters handling Anja or Jonas.

These flaws and a desire “to make the system more stable,” BStO’s story goes, led to its decision last fall to handicap online buying on certain mornings in 2016–17. How? A delay is “activated” when events in heavy demand go on sale, postponing the moment the buyer “gets access” to the online box office, called in German the Webshop (or occasionally Onlineshop). Phone and in-person selling, meanwhile, proceed as usual from the 10 a.m. start time.

Understandably the opera company has never announced the handicapping, and sources familiar with the Tageskasse scene say CTS Eventim’s system had nothing to do with the decision. The real motive, according to these sources, is to try to replicate online the speed of the physical line (queue) at the Tageskasse following years of grumbling from people who buy that way, and from staff too. A tug-of-war between Internet users and the bricks-and-mortar crowd has accordingly shifted in favor of the latter.

Out-of-town buyers are the worst hit, having fewer routes to tickets. Bavarians resident outside their capital city — it is the “state” opera after all — and fans of the renowned company as far away as East Asia and North America greatly rely on the Webshop.

The disadvantage is not new at BStO. Indeed the artificial online delays effectively bring to the main season the same narrow price availability for out-of-towners they have long experienced with BStO’s 142-year-old summer Munich Opera Festival. Tickets for the festival are first sold in snowy January in person only, and the lower four of eight price categories — roughly, seats below €100 for major performances — sell out this way when the biggest stars are scheduled, months before online ticketing starts.

Countless customers were surprised by the handicap on Jan. 12, 14, 18, 22, 30 and Feb. 2 while trying to buy tickets for Philipp Stölzl’s new production of Andrea Chénier, due March 12 and starring — gosh — both Harteros and Kaufmann. All performances were affected on those selling mornings, corresponding to BStO’s two-month lead time.

Surprised, and confused actually. The handicap throws up two screens in place of the Webshop. First, a countdown page, labeled with the quaint metaphor “waiting room” to dupe people into thinking the system is too burdened to process their order. This assigns a wait number, which ironically turns out to be far from “stable.” Then comes a standby page, for buyers whose number has dropped to 0 (zero) before the Webshop opens, i.e. before 10 a.m. — a strange situation, one might think, but the only one with potential to yield broad ticket choice.

Not-so-hypothetical scenarios:

Unaware of the handicap, she logs on at 9:55 a.m. She faces not her expected Webshop but the countdown page. (She would be there regardless of what event and date she is pursuing. The whole operation is impacted that morning because one heavy-demand performance is going on sale.)

She has of course no idea when the handicap was activated. (The answer could be 6 a.m., about when a physical line might start outside the Tageskasse.) But she is less troubled than buyers who may have purposefully stopped work in Tokyo or climbed out of bed in Boston.

She sees 29 lines of precise instructions auf Deutsch, unless she has opted for English screens, in which case she sees a remarkably compressed version of just five lines. (The complete English is here.) Key instruction: “Do not refresh.” Below, she reads her wait number: a high one, 400. Her chances are nil, but she doesn’t know this. She ties herself up for an hour before learning.

Logs on at 5:55 a.m. She is too early and goes straight into the normally functioning Webshop. She assumes she can just wait there until 10 a.m. But no. She must refresh the screen every twelve minutes or be disabled for inactivity. No instructions say this because the system was in normal mode when she entered. (To see them, she would have had to arrive via the countdown page and witness her wait number drop to 0 before 10 a.m.)

When she casually returns to the screen at 9:30 a.m., she discovers the Webshop inactive for her. She reloads. Now she is on the countdown page with number 200. Again no chance.

Fares better. He logs on at 6:15 a.m., apparently just after the handicap was activated. He lands on the countdown page with number 10. Like A, he is told not to refresh. He obeys. Later, but before 10 a.m., his number drops to 9, then 7. He wonders how this could be. No orders are being processed. (Possible answer: people on the standby page are failing to refresh and losing their place.)

But for him to succeed, his number must drop to 0 by 10 a.m. Otherwise, whether he’s at 400 or 4, he will be stuck on the countdown page during the crucial initial selling minutes.

Luckily he does drop to 0. He is moved to the standby page, a promising but precarious place. There he sees the instruction to refresh that N missed. He must do this every twelve minutes until 10 a.m. If he has arrived on the standby page early, say at 7:15 a.m., he will be doing a lot of refreshing. Should he fail — just once — he will find himself back on the countdown page holding a high number. (Anja and Jonas never wanted it that way.)

When the hour rolls around and the handicap ends, he must be ready, as in the past, to point and click with decisiveness and accuracy. His seats are secure only when they appear in his Einkaufswagen, the shopping cart.

A, N, and R may be imagined. The following numbers are real, recorded during the Jan. 18 handicap on Andrea Chénier ticketing in checks using two browsers and two connections:

Logging on at 10:24 a.m., a wait number of 688 with 170 seats left to sell. Three minutes later, wait number 346 with 130 seat left. At 10:43 a.m., number 179 with 38 seats. At 10:54 a.m., number 40 with 19 seats. After another five minutes, access to the Webshop with 4 seats shown as available. By 11:04 a.m., 2 seats left but neither one of them moveable into the shopping cart. At 11:07 a.m., sold out, Ausverkauft. Despite this, a new buyer could log on at 11:10 a.m. and receive wait number 382, which would drop to 0 six minutes later and lead to an empty Webshop.

Bavarian State Opera should end this nonsense. The company is damaging its reputation and working against its own carefully evolved ticket structure and sales procedures, designed to draw people of all income levels from a broad geography.

Those procedures sell tickets three ways: subscription; single-event by written order; and single-event by immediate fulfillment. The latter two are processed on a staggered basis according to performance date. Written orders (traditional mail, fax, email) are worked three months out. Immediate-fulfillment sales (online, phone, physical presence in the Tageskasse) begin two months out.

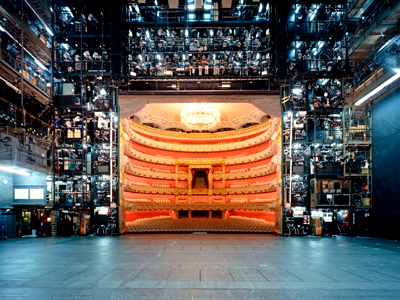

Each single-event method draws on fixed set-asides, or Kontingente, of seats in the 2,100-seat National Theater. These are broken down across BStO’s eight price categories and to within specific seating blocks, to as few as two seats, allowing near-total price and seat choice for each method. Quite sophisticated. And really quite fair, at least in the case of written orders. Even without handicapping, though, buyers outside Munich have less access to the immediate-fulfillment set-asides: getting to the Tageskasse may not be possible, and phoning is hard when there is heavy demand. Naturally they depend on the Webshop — and their hot connections, firm wrists, pinched fingertips and nanosecond nerves.

CTS Eventim, far from warranting criticism, could be held up as a most capable and user-friendly ticketer. Certainly its system offers an easier buyer interface, more precise seat sectioning, and lower fees, than that of the larcenous near-monopoly Stateside.

Instead of blaming its vendor, the opera company needs to go back to the future and solve its delicate Tageskasse problem with rigor and honesty. This means two things: adjustments to the Kontingente to reasonably protect in-person buyers; and an announcement of the change. Any tactic resulting in Internet screens that mislead buyers and waste their time, or too weird to spell out in a news release, is a bad one.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Staatsoper Imposes Queue-it

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Antonini Works Alcina’s Magic

Portraits For a Theater

Staatsoper Objects to Report

Tags:Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Commentary, CTS Eventim, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, News

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Bolton Saves Rameau’s Indes

Sunday, August 7th, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: August 7, 2016

MUNICH — Two evenings after an “Allahu Akbar” eruption here cost nine mostly teenage, mostly Muslim, lives, it felt perverse to indulge in 280-year-old French escapism stretching to Turkey, Peru, Iran and the future United States.

But there we were July 24 in the Prinz-Regenten-Theater for Bavarian State Opera business-as-usual, a festival yet, and Rameau’s four-entrée Les Indes galantes as imagined by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, the Belgian choreographer with stage-director pretensions.

And safer we were, too, than at a smaller music festival 110 miles away near Nuremberg, the outdoor Ansbach Open, where a Syrian refugee denied asylum in this country was preparing to explode his metal-piece-filled backpack among two thousand listeners. (As luck would have it, Germany’s first suicide bomber killed only himself when he detonated only his detonator and did so outside the festival’s gates, not having known in advance he would need a ticket.)

Before departing for Turkey, the opéra-ballet states its premise by means of a prologue: European lovers pressed to exchange Goddess Hébé’s doux instants (sweet moments) for Goddess Bellone’s gloire des combats can count on intercession from a third god, Amour, as they “traverse the vastest seas” in military service.

This plays out with amusing dramatic variance* in the four locales to music of beguiling harmony and bold instrumental color, in airs, vocal ensembles, choruses and dances. The U.S. entrée concludes with the Dance of the Great Peace Pipe (penned after Agapit Chicagou’s 1725 Paris visit), minuets, a gavotte, and a most charming chaconne.

If you kept your eyes closed, the performance was a treat. Opening them invited confusion, or worse, despite Cherkaoui’s fresh dance moves, tirelessly executed by his Antwerp-based Compagnie Eastman.

Ivor Bolton and the Münchner Festspiel-Orchester, an elite Baroque pick-up band, served Rameau with verve and expressive breadth, ripe string sound and fabulous wind playing. The Balthasar-Neumann-Chor from Freiburg managed its musical challenges neatly, in opaque French.

The score’s 17 roles went to ten generally stylish soloists. Lisette Oropesa proved a graceful musician in the lyric soprano duties of Hébé and Zima. Anna Prohaska, as Phani and Fatime, stopped the show with a divinely phrased Viens, Hymen, viens m’unir. Light tenor Cyril Auvity sang artfully as Valère and Tacmas, while John Moore’s baritone lent a golden timbre to the sauvage Adario. Reveling grandly in the music’s depths were basses François Lis (Huascar and Alvar) and Tareq Nazmi (Osman and Ali).

But soprano Ana Quintans encountered pitch problems as Amour and Zaïre; Elsa Benoit, the Émilie, seemed squeezed by Rameau’s nimble turns; Mathias Vidal pushed harshly for volume in the tenor roles of Carlos and Damon; and bass Goran Jurić, in drag as Bellone, muddied her vital rousing words.

As for the staging, new on this night, conceit and a ruinous idea got the better of Cherkaoui (and BStO managers, who should have intervened if they care about Baroque opera as they profess): he would thread together the prologue and entrées into one dramatic unit. Characters would appear in each other’s sections, mute. Opéra-ballet form be damned.

In place of exotic lands (requiring exotic sets and costumes), the viewer would journey from schoolroom to museum gallery to church to flower shop, to no place, to some closed border crossing. The spectacle of Peru’s Adoration du Soleil, for instance, would unfold in the church. Woven throughout, clumsily, would be tastes of the plight of Europe’s present refugees, and Europeans’ poor hospitality. Count the ironies.

[*In Turkey a melodrama, as the shipwrecked lovers’ fate turns on Osman’s magnanimity (Le turc généreux). In Peru a tragedy, as the couple’s freedom results from Huascar’s molten-lava death (Les incas du Pérou). In Iran a bucolic, as two pairs of lovers ascertain their feelings through disguise and espial (Les fleurs, original version of Aug. 23, 1735). In the U.S. a comedy, as noble savage Zima flirts with and mocks two European colonists, reversing the pattern, before homing in on loving native Adario (Les sauvages).]

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Portraits For a Theater

Nitrates In the Canapés

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Blacher Channels Maupassant

On Wenlock Edge with MPhil

Tags:Ana Quintans, Anna Prohaska, Balthasar-Neumann-Chor, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Compagnie Eastman, Cyril Auvity, Elsa Benoit, François Lis, Goran Jurić, Ivor Bolton, John Moore, Kritik, Les Indes galantes, Lisette Oropesa, Mathias Vidal, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, Prinz-Regenten-Theater, Rameau, Review, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Tareq Nazmi

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Sunday, July 17th, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: July 17, 2016

MUNICH — When Anja Harteros was singing her first Toscas three seasons ago, it was clear she had the vocal resources for the role, and the Mediterranean temperament. Even so, the portrayal didn’t quite compute.

Enter Bryn Terfel, a Scarpia to rattle the aloofest, longest-legged of prima donnas. And Jonas Kaufmann, trusted stage buddy, sweet Cavaradossi. Now the diva’s doubt, fear, passion and rage turn on the instant, her slashing knife grip extending a ferrous will.

Harteros fairly lived the part July 1 here at the National Theater, teamed as she must have wanted and apparently undeterred by Luc Bondy’s clunky 2009 stage conception. Warm chest tones and creamy highs, floated or hurled, came into thrilling dramatic focus this time around. Illica and Giacosa’s words made inexorable sense, the Attavanti canvas and Terfel’s guts sure targets.

The tenor, too, had a great night: astutely colored phrases, gleaming top notes, a clarion but unexaggerated Vittoria! For once, E lucevan le stelle emerged as spontaneous thought, always in Kaufmann’s wonderfully lucid Italian.

If the mighty Welshman sounded a smidgen less opulent of voice than in previous Munich Scarpias, his characterization was as potent as ever, and his savoring of Puccini’s lines most enjoyable.

The snag, alas, was Kirill Petrenko’s conducting. Forceful and weighty, it never felt rooted in the language it was supposedly driving. Still, a terrific night for the Munich Opera Festival, and nowhere more refined than during Io de’ sospiri as sung by the Tölzer Knabenchor’s uncredited soloist.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Manon, Let’s Go

Tonhalle Lights Up the Beyond

Busy Week

Time for Schwetzingen

Schultheiß Savors the Dvořák

Tags:Anja Harteros, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bondy, Giacomo Puccini, Kaufmann, Kirill Petrenko, Kritik, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Review, Terfel, Tölzer Knabenchor, Tosca

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Mastersingers’ Depression

Tuesday, May 17th, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: May 17, 2016

MUNICH — Beckmesser blew his brains out at the end of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg last night here in the Nationaltheater. That was after first aiming his gun at the back of the head of Sachs, and after a graphically brutal beating by David and bat-wielding apprentices had left him in a wheelchair — a predicament from which he had miraculously recovered, back onto his feet, within the few hours separating Johannisnacht and Johannisfest. Sachs, for his part, never saw the gun; he was sitting moping because Stolzing had ignored his Verachtet mir die Meister nicht, had declined to honor German art or the masters safeguarding it, and had simply walked out with Pogner’s prized daughter.

Whether Beckmesser’s character is of the suicidal type is a fair, though in context minor, question. Stage director David Bösch’s new production for Bavarian State Opera offers an altogether transformed view of Wagner’s erstwhile comedy, funded by the same hardworking Bavarian people who brought you the first, on June 21, 1868, when Hans von Bülow occupied GMD Kirill Petrenko’s podium.

Swiss-trained Bösch explores the role art can play in society by winding the clock in the opposite direction from the composer. Instead of reaching back three centuries to show the art-guild tradition at its liveliest, when Nuremberg prospered, he forwards us to a faceless town that has seen better days, where the institution feted by Wagner is in yet more jeopardy than when the score was written and where the masters in their trades suffer the effects of debilitating, distant economic forces. Somewhat outside these problems is the presumably flush Stolzing, but even he cannot invigorate through his candidacy a guild whose masters find it easier to delude themselves than honestly confront demise. Sachs’s Wahnmonolog fits right in. Not much else does.

The idea of collective depression finds little use for such musical-dramatic particulars as the scent of the Flieder (lilac) or the shade of the Linde (basswood). Bösch has to invert the humor in, for instance, the Nachtwächter’s round and Sachs’s gift to Beckmesser. He defies Wagner’s time-of-day and lighting directives. Indeed, clashes with the composer create an uneasy mix of narrative, pomp, violence and slapstick (song-trial errors marked via shocks to the applicant in an electric chair; a town-clerk serenade from atop a scissor-lift, constantly raised and lowered by the cobbler).

But Bösch’s own visual-stylistic trademarks are firmly in place, reminding us of his spacy, zoned-out previous work for this company: L’elisir d’amore (2009), Mitridate, rè di Ponto (2011), and, his touching flower-power effort, La favola d’Orfeo (2014). Neatly arranged decay, locally lit props, black limbo backgrounds, a funky insouciance to the stage action: these are some.

The Bavarian State Opera Chorus sang magnificently for this premiere, achieving levels of expressive detail and shading it reserves for its obsessive GMD; Sören Eckhoff did the coaching. Sara Jakubiak from Bay City, MI, made a welcome debut as Eva, acting well and producing girlish tones in mostly clear German. Benjamin Bruns coped sweetly with the boisterous lyric challenges of David. Jonas Kaufmann added the quality of heroic delivery to the youthful ardor and Lied skills evident in his Scottish Stolzing of long ago. Wolfgang Koch, vocally opulent, looked sloppy as Sachs but conveyed enlightenment anyway. He projected his words impeccably and never forced for volume. Markus Eiche’s musically ideal Beckmesser deserved and received the loudest applause, after tough toiling in Bösch’s action. Christof Fischesser intoned nobly and richly through Pogner’s wide vocal range, while the Nachtwächter’s chant seemed all too short as securely phrased by Tareq Nazmi.

Petrenko drew playing of color and sparkle from his Bavarian State Orchestra, favoring momentum (78’ 58’ 70’ 42’) over reflection but pointing the rhythms with ceaseless energy and emphasis, much to the opera’s advantage. Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg will be streamed as video over the Internet at 5 p.m., Munich time, on July 31, 2016, under sponsorship from Linde.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

See-Through Lulu

Time for Schwetzingen

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

Mariotti North of the Alps

MKO Powers Up

Tags:Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerischer Staatsopernchor, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Benjamin Bruns, Christof Fischesser, David Bösch, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Kaufmann, Kirill Petrenko, Kritik, Markus Eiche, München, Munich, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Review, Sara Jakubiak, Sören Eckhoff, Tareq Nazmi, Wolfgang Koch

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Petrenko Hosts Petrenko

Friday, April 22nd, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: April 22, 2016

MUNICH — Vasily Petrenko’s debut at Bavarian State Opera this weekend prompts a glance at two Russian-born, modestly profiled conductors who have built distinct careers in Western Europe while sharing a last name. The guest from Liverpool will lead Boris Godunov, last revived two years ago by company Generalmusikdirektor Kirill Petrenko.

Inviting Vasily to work in Kirill’s house was sweet, ingenuous. After all, the two Petrenkos are what trademark attorneys call “confusingly similar” marks, a factor that doesn’t vanish just because real names are involved, or because it’s the arts. Are artists products? Their work is, notwithstanding the distance from commerce.

The Petrenkos are not of course the first conductor-brands to overlap, but unlike the Kleibers or Järvis, Abbados or Jurowskis, no disparity of talent or generation neatly separates them. Then, inescapably, there is the matter of dilution: a “Toscanini” needs no specifier.

As it happens, agents have promoted the Petrenkos as if with accidental care over geography. Although both men have enjoyed positive forays Stateside, awareness of them in Europe diverges. For a full decade, Vasily has been the “Petrenko” of reference in Britain. Kirill has been “Petrenko” in Germany.

Kirill has had such minimal renown in Britain, in fact, that retired Bavarian State Opera chief Peter Jonas last summer on Slipped Disc could report the following about the Bavarian State Orchestra’s upcoming European tour: “The [orchestra’s] committee and their management offered themselves to the [BBC] Proms for 2016 … and were sent away with the exclamation, ‘Oh no … . Kirill Petrenko? We do not really know about him over here.’ … The tour will happen all over Europe but without London.” Indeed it will.

In the meantime, Calisto Bieito’s staging of Boris Godunov gets a three-night revival April 23 to 29 with a strong cast: Sergei Skorokhodov’s pretender, Ain Anger’s chronicler and Alexander Tsymbalyuk’s riveting Boris. How will Vasily grapple with the (1869) score? Opera featured prominently in his career only at the start.

Echo Klassik Award

Placing the two Petrenkos side by side here, like baseball cards, meant compiling at least some personal facts along with the musical. So, three questions went to the conductors’ handlers. How tall is he? Where does he live (part of town)? What’s his favorite sports team?

This proved awkward, however, especially on one side, and hitherto-cordial staffers turned as cool as, well, trademark attorneys. Vasily’s people cooperated with partial answers. Kirill’s, deep inside Bavarian State Opera, stonewalled: “Mr. Petrenko generally does not wish to answer any personal questions.”

As it turned out, Vasily was on record with full answers over the years to all three questions for various media outlets. The man is an open book. This left Kirill’s side with unflattering holes. But the opera company’s hands were tied. Apparently under instructions from the artist, nobody could even confirm he lives in Munich (where he has drawn a paycheck for 30 months already). And he may not.

Bavarian State Opera: “What’s not to understand about ‘Mr. Petrenko does not wish to answer any personal questions’? Who puts out the rule that a conductor … does have to comprehend or be willing to be part of public relations? … So, in fact, we do not want to convey anything to anybody. This is the ‘line to be drawn’ from our side.”

Mention of Vasily went over badly. BStO: “What kind of idea is it anyways to compare two artists because they share the same last name?” Prepared descriptors accompanied the rhetoric: “ridiculous” and a “game.” How not to kill a story.

Shown the data for the above table, the opera company took to sarcasm: “Yes, sure, [inventing] height and weight [measurements] is of course totally acceptable.” But Kirill’s height had become public half a year ago* at ARD broadcaster Deutsche Welle. BStO did not either know this or wish to share the knowledge. Its hapless official scanning DW: “Oh, it’s on the Internet! It’s gotta be true!”

[*Earlier actually: Lucas Wiegelmann included it in an excellent 2014 discussion for Die Welt.]

Photos © Bayerische Staatsoper (Kirill Petrenko), Royal Liverpool Philharmonic (Vasily Petrenko)

Related posts:

Petrenko’s Sharper Boris

Portraits For a Theater

Bieito Hijacks Boris

Nazi Document Center Opens

Petrenko to Extend in Munich

Tags:Ain Anger, Alexander Tsymbalyuk, Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Boris Godunov, Commentary, Kirill Petrenko, München, Munich, Mussorgsky, News, Oslo Philharmonic, Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Sergei Skorokhodov, Vasily Petrenko

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Six Husbands in Tow

Sunday, March 13th, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: March 13, 2016

MUNICH — Some contracts come with strings attached, others with husbands. In a remarkable set of coincident artistic priorities for company boss Nikolaus Bachler — or a broad capitulation — Bavarian State Opera’s 2016–17 season, announced today, features no fewer than six divas in performance with their husbands. Edita Gruberová, Elīna Garanča and Kristine Opolais will star in Roberto Devereux, La Favorite and Rusalka while their other halves conduct. Diana Damrau, Anna Netrebko and Aleksandra Kurzak will headline Lucia di Lammermoor, Macbeth and La Juive while alongside them their spouses sing. In another family tie, Vladimir Jurowski has apparently been allowed to abandon the new Ognenny angel he led (electrically) this season in favor of … his dad. Small wonder 2016–17 is dubbed “Was folgt”: What follows.

Photos © Wiener Staatsoper (Elīna Garanča), Opernhaus Zürich (Anna Netrebko), Bill Cooper for the Royal Opera House (Kristine Opolais), Catherine Ashmore for the ROH (Aleksandra Kurzak, Diana Damrau), Wilfried Hösl (Edita Gruberová)

Related posts:

Kaufmann, Wife Separate

Antonini Works Alcina’s Magic

Manon, Let’s Go

Poulenc Heirs v. Staatsoper

Concert Hall Design Chosen

Tags:Aleksandra Kurzak, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Commentary, Diana Damrau, Edita Gruberová, Garanča, Kristine Opolais, La Juive, Lucia di Lammermoor, Macbeth, München, Munich, Netrebko, News, Nikolaus Bachler, Ognenny angel, Roberto Devereux, Vladimir Jurowski

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Die Fledermaus Returns

Sunday, January 31st, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: January 31, 2016

MUNICH — Three years ago Bavarian State Opera’s yearly Silvester performances of Die Fledermaus came to a sudden, poorly excused halt. Never mind that they were a global signature of the company; Carlos Kleiber famously led ten of them. As substitutes, the powers-that-be provided La traviata (Verdi was 200) and then, weirdly, L’elisir d’amore. But last month the bat returned, courtesy of GMD Kirill Petrenko, who, it turns out, is as much a fan as Kleiber and a tautly disciplined but supple musical advocate. Indeed he conducted gleefully Dec. 31 and Jan. 4 yet with his customary, at times martial, intensity, the carotid arteries alarmingly discernible — which did not preclude ballerina-like poses, hands high, fingers pointed together, for stylish delays in Johann Strauss’s three-four time. The orchestra sizzled. The chorus sang with astonishing precision and expressive warmth, not least for Brüderlein, Brüderlein und Schwesterlein. Oozing charm and impeccable in their comic timing as the Eisensteins were Marlis Petersen and Bo Skovhus. She sang, also danced, a seductive table-top Klänge der Heimat, ending on the eighth-note high D, as written, although less than forte. Anna Prohaska brought moxie and what may have been a fine Lower Austrian drawl, not much volume, as the “Unschuld vom Lande.” Edgaras Montvidas contributed an ardent, grainy-sounding Alfred, Michael Nagy a mellifluous Falke, mezzo Michaela Selinger a game but too-bright-sounding Orlofsky; her party guest, Thomas Hampson, in town to prepare for Miroslav Srnka’s costly new opera South Pole, interpolated a lavish Auch ich war einst ein feiner Csárdáskavalier … Komm, Zigan, spiel mir was vor. Missing, alas, was the magnetic Alfred Kuhn, long a definitive, droll Gefängnisdirektor Frank here (also Antonio the gardener and Benoît the landlord); in context, Christian Rieger looked and sounded awkwardly robust. Andreas Weirich’s rethinking of the old Leander Haußmann production worked best in Acts I and II. The cramped jail action sputtered, and Viennese actor Cornelius Obonya, a Salzburg Jedermann, went on too long as Frosch; he will be replaced this coming New Year’s Eve by a Bavarian.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Petrenko’s Rosenkavalier

Verdi’s Lady Netrebko

See-Through Lulu

Petrenko’s Sharper Boris

Manon, Let’s Go

Tags:Andreas Weirich, Anna Prohaska, Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerischer Staatsopernchor, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Bo Skovhus, Carlos Kleiber, Christian Rieger, Cornelius Obonya, Die Fledermaus, Edgaras Montvidas, Johann Strauß, Kirill Petrenko, Marlis Petersen, Michael Nagy, Michaela Selinger, München, Munich, Review, Thomas Hampson

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Poulenc Heirs v. Staatsoper

Thursday, January 7th, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: January 7, 2016

MUNICH — Bavarian State Opera will defy the heirs of Francis Poulenc and proceed with revival performances of its literally explosive staging of Dialogues des Carmélites later this month, the company said today.

The 2010 production by Dmitri Tcherniakov departs from the scheme of the composer and the source novelist, Georges Bernanos, in several ways and has been described by the heirs as a “trahison.” Not the least of its transgressions is a substitution in the climactic scene: a deadly gas blast and one self-sacrifice (by Blanche) replace the serial guillotining of the titular nuns laid out graphically in the music.

In a Dec. 23 letter to the Munich company, the heirs demanded that the “rights-infringing staging of the work (ihren Rechten verletzenden Aufführung des Werkes)” be put to “no further use.”

But a slow-won French court victory for the heirs last October constrained only BelAir Classiques and Mezzo TV from, respectively, selling DVDs of the production and screening it. The estates of both Poulenc and Bernanos had begun legal proceedings in October 2012, perhaps not aware of the nature of Tcherniakov’s efforts until BelAir’s DVD release that year. The last onstage revival came, by coincidence, the same month.

Poulenc’s 1956 opera is evidently less tightly controlled, or protected, by his heirs than is, for example, Gershwin’s 21-years-older Porgy and Bess by the American composer’s estate.

In justifying the resolve to proceed, Bavarian State Opera’s Geschäftsführender Direktor Roland Schwab said: “In the context of an earnest grappling with the work, the stage direction must have the freedom to deviate from history. Thus the work is not disfigured, but rather its ideas are depicted from today’s viewpoint.”

The company also noted it had made no alteration to libretto or score. This despite the stripping out of all Christian reference as well as the guillotining from the stage action. BStO Intendant Nikolaus Bachler is a firm, one might say notorious, defender of unfettered Regietheater.

Not only will the show go on, but Bavarian State Opera is supporting BelAir Classiques and Mezzo TV in their appeal of the October court decision, the company said.

Scheduled to sing the opera Jan. 23 to Feb. 1 are Christiane Karg as Blanche, Anna Christy as Constance, Anne Schwanewilms as Lidoine and Stanislas de Barbeyrac as the Chevalier. Susanne Resmark and Sylvie Brunet reprise their roles as Marie and de Croissy on the banned 2010 DVD. Bertrand de Billy conducts.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Poulenc DVD Back On Market

Thielemann’s Rosenkavalier

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

Tonhalle Lights Up the Beyond

Antonini Works Alcina’s Magic

Tags:Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, BelAir Classiques, Commentary, Dialogues des Carmélites, Dmitri Tcherniakov, Mezzo TV, München, Munich, News, Nikolaus Bachler, Poulenc, Roland Schwab

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Ettinger Drives Aida

Wednesday, September 30th, 2015By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 30, 2015

MUNICH — Bavarian State Opera’s irredeemably banal 2009 Aida has been spiffed up and its awkward action scheme apparently restudied for a fall run here. Even so, the honors at Monday’s performance (Sept. 28) belonged firmly with the musicians, instrumental and vocal. Mannheim-based conductor Dan Ettinger exerted a Karajan-like grip, stirring Verdi’s music from the bottom up, parading its rhythmic strengths, brashly stressing percussive detail, and inevitably drawing attention to himself. Which is not to say he drowned everyone out: he accompanied attentively and savored well-rehearsed balances. The Bavarian State Orchestra cooperated gamely; the Bavarian State Opera Chorus sang with rare refinement in clear Italian. Krassimira Stoyanova acted so credibly and poignantly through her essentially lyric voice that nobody would have guessed she is new to this opera. Her sound was pure and unforced, her phrasing properly noble for the title role. Amneris suits Anna Smirnova better than did Eboli here four seasons ago, but her communicative singing in Acts III and IV followed a numb, robotic portrayal before the Pause. Jonas Kaufmann proved he can sing Radamès outside of studio conditions, and thrillingly, starting with an exquisitely shaped Act I Romanza and progressing to generous, imaginative ensemble work. Franco Vassallo’s warm and unstrained Amonasro, Ain Anger’s formidable Ramfis, and Marco Spotti’s eloquent Rè d’Egitto completed a straight-A cast of principals.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Verdi’s Lady Netrebko

Nézet-Séguin: Hit, Miss

Chung to Conduct for Trump

Christie Revisits Médée

Time for Schwetzingen

Tags:Aida, Ain Anger, Anna Smirnova, Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerischer Staatsopernchor, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Dan Ettinger, Franco Vassallo, Giuseppe Verdi, Kaufmann, Krassimira Stoyanova, Kritik, Marco Spotti, München, Munich, Review

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Blogs

Archives

Tags

Meta

Musical America Blogs is proudly powered by WordPress

Entries (RSS) and Comments (RSS).