By ANDREW POWELL

Published: July 4, 2017

OBERAMMERGAU — Amplification makes it possible; amplification limits the achievement. That is the dilemma for opera in this neat Bavarian town’s Passionstheater (1930), built to service a post-plague pledge made 384 years ago. Raked seating in the barn-like house confronts a fixed templar structure on a stage open to the elements, where, every ten summers, the community enacts the suffering and death of Jesus as a story of hope and salvation. (The Passion play returns for a hundred performances in 2020.) In the off-years there has been Shakespeare, Ibsen, ballet, and so on. Then, two summers ago, came a first try at opera, Nabucco. Stage director Christian Stückl, himself an Oberammergauer, teamed up with young Latvian conductor Ainars Rubikis, setting the action at Palmyra: “Nabucco with Kalashnikovs,” noted the Süddeutsche Zeitung; anyway, with results stable enough to repeat last year.

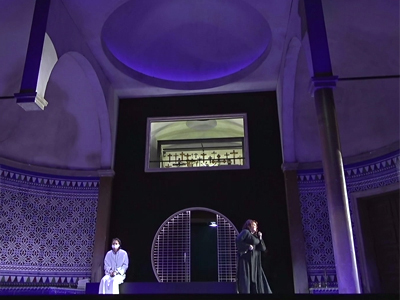

On Friday (June 30) the same duo turned to the non-biblical yet still heavily choral pages of Der fliegende Holländer, deploying the refined skills of 180 devoted local choristers, the Chor des Passionstheaters Oberammergau. The new production features a revolving central unit painted expertly as a rolling sea under the temple roof; from this spew the Dutchman and his eerie Mannschaft. To the sides, plain navy flats fan out. Stückl directs traffic astutely, above all the large choral bodies. His corny humor in Act II and a mute wandering boy detract. Unlike at Erl, where another Passion-play facility is used for Wagner, Oberammergau has a bona fide orchestra pit, one even recessed below the stage à la Bayreuth. But the sound is poor enough to necessitate amplification, and the boosted instruments force miking on the singers too. From the opening strains of the overture at this premiere, an electronic aura marred the sound. Later the mic balances favored the voices so that the pulse of the accompaniment barely registered in the house. Double basses and cellos were heard to disadvantage throughout, while ambient miking and the vagaries of body mics caused solo and choral voices to be picked up in unmusical ways.

Despite all this, Gábor Bretz, 43, magnetized attention in his role debut as the Dutchman, producing effortless deep rich sound and expressive legato lines in clear if gently accented German. (Bretz’s kids, all seven of them, had created their own festive stirs at Oberammergau’s main ice-cream joint during the week; their mom last year opened an artisanal chocolate shop in old Buda.) Liene Kinča sang Senta over a cold. Unflattered by the mics, she coughed politely after the Ballad. Denzil Delaere, the Steuermann, offered sweeter tones than did the dramatically vivid yet straining Erik of David Danholt, while Guido Jentjens chopped up Daland’s lines ineptly. Rubikis drew enthusiastic work from the young-professional Neue Philharmonie München at lively tempos, but gauging any nuances or insight was impossible. As darkness took hold and Alpine breezes wafted in, the temperature plunged; brief bursts of rain hit the wooden roof. The performances continue over four weeks.

Photo © Arno Declair

Related posts:

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Wagner, Duke of Erl

A Complete Frau, at Last

Blacher Channels Maupassant

On Wenlock Edge with MPhil

Guillaume Tells

Wednesday, September 23rd, 2015By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 23, 2015

MUNICH — Post is under revision.

Still image from video © Bayerische Staatsoper

Related posts:

Nitrates In the Canapés

Muti the Publisher

Honeck Honors Strauss

Kušej Saps Verdi’s Forza

Time for Schwetzingen

Tags:Amanda Forsythe, Andrew Foster-Williams, Antonino Fogliani, Antonio Pappano, Antú Romero Nunes, Bad Wildbad, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bongiovanni, Bryan Hymel, Camerata Bach Chor Poznań, CD, Commentary, Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Damiano Michieletto, Dan Ettinger, Decca, DVD, Evgeniya Sotnikova, Gerald Finley, Graham Vick, Guillaume Tell, Günther Groissböck, Jochen Schönleber, John Osborn, Juan Diego Flórez, Judith Howarth, Kritik, Luca Tittoto, Malin Byström, Marina Rebeka, Michael Spyres, Michael Volle, Michele Mariotti, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Naxos, Nicola Alaimo, Nicolas Courjal, Opus Arte, Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Pesaro, Raffaele Facciolà, Review, Rossini, Rossini Opera Festival, Royal Opera House, Sofia Fomina, Tara Stafford, Virtuosi Brunenses

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed