By ANDREW POWELL

Published: November 23, 2012

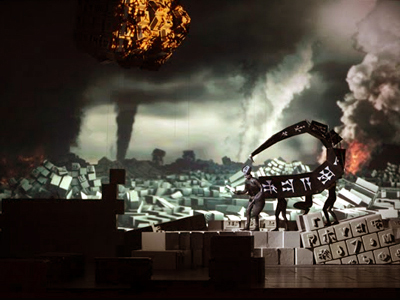

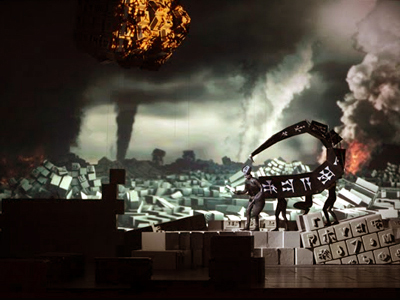

MUNICH — Scorpion-Man prowls the rubble of an unnamed flattened city at the start of Babylon, Jörg Widmann’s new opera, wailing as he moves. We should care.

Seven scenes, a Hanging Garden interlude, and three costly theater hours later, he is back, doing his thing over the same debris, also multiplying himself, and alas we have not cared or even learned what he represents. Perhaps he is us sad cityites, predatory and detached from our souls.

Widmann’s librettist for this Bavarian State Opera commission (heard and seen Oct. 31) is the post-humanist philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, whose worries, intra-urban and intra-galactic, drive Babylon in one big circle against the backdrop of the 6th-century-BC Jewish exile.

Sloterdijk’s narrative feebly pivots on a love-interest, in the persons of exile Tammu and local priestess Inanna. The character Soul is catalyst in a progression of these two that ends, before the circle has closed, in a concordance of Heaven and Earth (cue sweet music).

Along the way, Tammu gets drugged, laid, sacrificed, resurrected, and flown away with his gal in a spaceship. After administering the drug and enjoying her man, Inanna’s one job is to descend post-sacrifice into the Underworld and retrieve him, being sure not to lose sight of him as they make their way out together.

If this suggests a too-rich stew of Isolde or Norma and Euridice with Tamino, it is. But we are in Babylon, and your bowl arrives as the Euphrates overflows, the New Year rings in at the Tower of Babel, and Ezekiel dictates the Word of God, not to list the antics of seven Sloterdijk planets and fourteen Poulenc-ish sex organs.

Born here in 1973 and locally esteemed, Widmann as composer is much identified with Wolfgang Rihm, one among several teachers and influences. He is, besides, a bold and expressive clarinetist: a 2012 Salzburg Festival performance of Bartók’s Contrasts with Alexander Janiczek and András Schiff all but vaulted off the Mozarteum’s platform, and a 2011 Munich partnership with the Arcanto Quartet found rare vigor as well as cozy plushness in Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet.

The Nabucco-era subject had taken the composer’s fancy long ago. Ideas sprouted. A raucous Bavarian-Babylonian March emerged as orchestral fruit last year, bridging the millennia if not exactly the cultures. At some point came the link with Sloterdijk and the decision to plough forth with an opera, Widmann’s sixth piece for music-theater.

Undaunted by the librettist’s loony layers, Widmann supplies for Babylon music of chips and shards and sporadic mini-blocks. 160 minutes of it.

He savors direct quotes, splintered just past the point of identifiability. These he takes from jazz, operetta, lute song, Baroque dance, cabaret, Hollywood, symphonies, band repertory. He crafts brief, pleasingly original blocks of sound in various forms — brass swells, percussive glitter, choral refrains, woodwind banter — deploying them to varying effect. He is a gifted colorist, writing with virtuosity for all sections of the orchestra, in this case a large one, heavy on low winds and percussion.

Vocally the writing is less fluent, less confident. Abrupt ascents are a peculiarity. The tessitura of all three principal roles — Inanna, the Soul and Tammu — lies coincidentally high for each of the voice types (two sopranos and a tenor). Vocal lines are often aborted, mid-flight, again producing small blocks.

Widmann’s chipboard elements are arrayed in rapid indigestible sequences some of the time (Scene III’s orgy). Elsewhere, thin writing overstays its welcome or fails to develop in sync with the cosmic-Biblical scheme (Scene V) — the “prolix musical treatment” George Loomis noted in his review.

Enter Carlus Padrissa, the busy Spaniard known for constant stage movement. Hired to define and motivate the opera’s characters and unite the threads in text and score, Padrissa delivers, well, movement.

The gloomy arthropod’s rubble swiftly morphs into moveable letterpress type: Cuneiform, Katakana, Cyrillic, Hebrew — ah, Babel, the universal translator — to be piled up by mummers, piled down, carried off, brought on. Nearly incessantly. Flown and raised platforms support and transport sundry participants, some of them needed. Projected screen-saver lines depict the restless Waters of Babylon. Moving photographic images reveal holy verse, hell fire, a meteor (or ICBM) crashing to Earth. There is always plenty to watch.

Still, two problems dog Padrissa’s circus-like approach to opera, evident in his 2007–9 Valencia Ring and 2011 Munich Turandot: movement everywhere deprives the action of focus; and physical space required for upstage activities (open wings, as in ballet) deprives the singers of sound boards (in the form of sets) to reflect and project their voices. So it is with Babylon.

In the Turandot — due by chance for Internet streaming in its revival on Sunday (Nov. 25), here, and significant for the textual decision to end where Puccini ended — the voice-projection problem is addressed by having much of the principal singing occur drably near the stage apron.

In Babylon it is addressed with amplification*, subtly on the whole, though on Oct. 31 individual vocal lines resounded unnaturally at several moments.

Generalmusikdirektor Kent Nagano brought to the new opera his dual virtues of judicious tempos and attention to balances. The orchestra played compliantly, David Schultheiß working as poised and able concertmaster. Anna Prohaska and Claron McFadden coped deftly with the vocal stratosphere as Inanna and the Soul. Gabriele Schnaut brought rolling majesty to the Euphrates personified. Countertenor Kai Wessel exuded glum fortitude as Scorpion-Man. Jussi Myllys, the Tammu, relished having more to do than in his numerous recent Jaquinos, serving Widmann’s music earnestly. Willard White, as Priest-King and as Death, growled and boomed with his customary expertise.

When final blackness came, the polite Bavarian audience registered its ennui not with boos but with the barest, most ephemeral applause. Reconciling Heaven and Earth had proven easier than reaching across the proscenium.

[*Bavarian State Opera in a Nov. 26 message noted that “amplification was used for some parts” of the opera and that Widmann “actually marked the use of amplification for the scenes with heavy orchestral instrumentation in the score.”]

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Levit Plays Elmau

Petrenko Hosts Petrenko

Manon, Let’s Go

Tonhalle Lights Up the Beyond

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

A Stirring Evening (and Music)

Wednesday, April 24th, 2013By ANDREW POWELL

Published: April 24, 2013

MUNICH — Members of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra venture six times a year to Lake Starnberg, some 20 miles southwest of here, to play chamber music at the Evangelische Akademie Tutzing, or EAT, as its website favicon reads. A mid-season program (Feb. 24) paired quintets by Mozart and Schumann in the venue’s airy music room, drawing skilled performances. But extra-musical ghosts disturbed this particular offering: concert tickets include a guided tour of EAT — once a lone lakeshore chapel, later a castle, palace and U.S. Army HQ — and our evening began with docent tales of, among other matter, a 1945 American troop obliteration of the palace library, Dwight Eisenhower’s name being dropped for good measure.

What? The troops fight their way into Bavaria, set up at Tutzing Palace to administer a new basis for democracy, and are remembered for trashing books? So much for perspective. Then again, Tutzing can seem stuck in the 1920s and 30s: Adolf Hitler’s beer-hall putsch buddy Erich Ludendorff is grandly buried there and the former fishing village memorializes “Hitler’s pianist” Elly Ney — Carnegie Hall attraction in 1921, ardent Nazi by 1933 — on its much-visited Brahms Promenade. Physically the town has changed little over the decades.

Our thoughts stirred by the guide’s earful, we crossed the yard for musical respite. Mozart’s G-Minor String Quintet, K516, resounded in handsome proportion and balance. Antonio Spiller, first violin, stressed the cheery second theme of the opening Allegro emphatically enough to prepare for Mozart’s abrupt turn in the closing movement. Leopold Lercher, Andreas Marschik and Christa Jardine partnered him attentively throughout, even if they couldn’t quite match his poise and confidence. Cellist Helmut Veihelmann intoned with care, but the ear craved more of a grounding, more cello volume. In the Schumann Piano Quintet, after a coffee break and snowy stroll by the lake (pictured), unrestrained collegial exchanges and pianist Silvia Natiello-Spiller’s buoyant passagework found color aplenty, even kitschy color. Marschik took the viola part.

EAT’s buildings date to medieval times. The small chapel got wrapped in a castle in the 16th century, its watery and Alpine views appropriated. Sundry owners and architects later morphed the premises into a modest post-Baroque palace. In 1947 the Lutheran Church assumed control, followed by ownership two years later in a 350,000-Mark deal. Tranquil seminars and coffee-table conferences now prevail along with occasional music events, such as those of the BRSO ensembles.

Given the pre-concert assertions and the irksome notion of book destruction, this U.S. listener decided on a little post-concert research. Quick findings: Eisenhower did spend time in Tutzing in the 1940s, returning there repeatedly for off-duty art lessons in 1951, but where he stayed isn’t clear; and the palace library did vanish during the 1939–45 war, but whether the honors fell to the U.S. Army isn’t clear at all. And regardless of what happened to the books, the American presence achieved positive results in Tutzing starting immediately.

Indeed, one life-saving story would well serve EAT’s docent and his Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR) pre-concert narrative. On the night of April 29, 1945, a train of prisoners — Russians, Romanians, Hungarians and Poles — pulled into Tutzing station. 800 in number and mostly men, they had been dispatched from Bavaria’s newly wound-down Mühldorf concentration camp, east of Munich, to the Tyrol, and to slaughter at the hands of waiting SS personnel. But a providential delay occurred — Tutzing is 90 minutes from the Tyrol — attributed variously to a faulty locomotive, a righteous local flagman, and even a prescient German commanding officer.

The next morning, on the same day that Hitler turned the lights out and Munich fell to the Allies, the XX Corps, part of George Patton’s U.S. Third Army, reached the town. Little fighting ensued because Tutzing was a Red Cross safe zone. The troops soon located the Benedictine Hospital crammed with wounded German soldiers, and the makeshift care beds arrayed in the high school and other buildings. Then they found the train, confronting directly the horror of camp survivors and at first wrongly concluding that Tutzing itself had been a camp location. The prisoners were told of their freedom, and the weakest removed from the train for treatment.

Decisive action followed. The American command seized a number of Tutzing homes for emergency use, instructing the locals to double up with their neighbors. The less seriously wounded of the German soldiers now lost their hospital beds to Mühldorf survivors in critical condition, the majority of them Jewish Hungarians. Although educated by the Reich to resist the enemy to the bitter end, many Tutzingers waved white flags for the U.S. troops, engendering whistles of censure from their more determined neighbors.

On May 1 the troops located a Nazi school campus on high ground in the next village, Feldafing, and rapidly commandeered it to serve as a new home and care facility for the former prisoners, now officially “displaced persons.” (Novelist and social critic Thomas Mann had owned a condo retreat in one of the campus buildings. He lived in Munich for 40 years before fleeing the country upon Hitler’s ascendancy in 1933.) On the morning of May 2, a working locomotive having been procured, the Todeszug crept back three miles the way it had come and transferred the survivors, giving them real beds and room to roam. Months later, after it became clear across Germany that ethnic groups among former prisoners did not always get along with each other, each displaced-person facility would become designated for a specific group, Feldafing for Jewish Hungarian survivors. With a population that eventually climbed above 4,000, the site would gain a reputation as “a place … to find missing people.”

The war raged for another five days before tacit German surrender May 7 at Reims. American troops requisitioned Tutzing Palace on June 7, setting up Army of Occupation HQ there three days later. This remained operative until the end of 1945, a pivotal command center at the very start of the 10-year Allied Occupation of Germany. In context, the books seem inconsequential.

Photo © Evangelische Akademie Tutzing

Related posts:

Brahms Days in Tutzing

Tutzing Returns to Brahms

BRSO Adopts Speedier Website

Tonhalle Lights Up the Beyond

Petrenko Hosts Petrenko

Tags:Andreas Marschik, Antonio Spiller, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Bayerischer Rundfunk, BR, Christa Jardine, Commentary, Dwight Eisenhower, Elly Ney, Erich Ludendorff, Evangelische Akademie, Feldafing, Helmut Veihelmann, Lake Starnberg, Leopold Lercher, Lutheran Church, Nazi Germany, Review, Schumann, Silvia Natiello-Spiller, Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Thomas Mann, Tutzing, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed