Note: This review marks the continuation of a series dedicated to showcasing the best student writing from the Dance History course I teach at The Juilliard School.

By Cleo Person

As a Southern California native, I eagerly awaited New York City Ballet’s February performance of Justin Peck’s new work Paz de la Jolla. Seated in the former New York State Theater, I was hoping for a mini trip home, minus the hassle and airfare. Even though Reid Bartelme’s costuming (bathing suits and shorts) and Peck’s ocean imagery did create some sense of a warmer California climate, not much else about the piece captured the laid-back, costal village atmosphere of La Jolla.

Peck, a twenty-five year old City Ballet corps member, is not a complete novice in the art of choreography. La Jolla is his fourth work for City Ballet, following his most recent critical success, Year of the Rabbit. But La Jolla, set to Bohuslav Martinu’s Sinfonietta la Jolla, didn’t win me over. Peck’s choreography rarely conjures any sense of La Jolla as an actual place. The ballet seems to be in the service of displaying the dancers’ high level of technical ability, and Peck’s choreographic proficiency. He skillfully arranges his 18 dancers in geometric formations and patterns through an array of steps that feature the classical ballet lexicon. It’s a charming, impressive display. However the confounding part about La Jolla is what it actually evokes: the urgent, frenetic pace of New York.

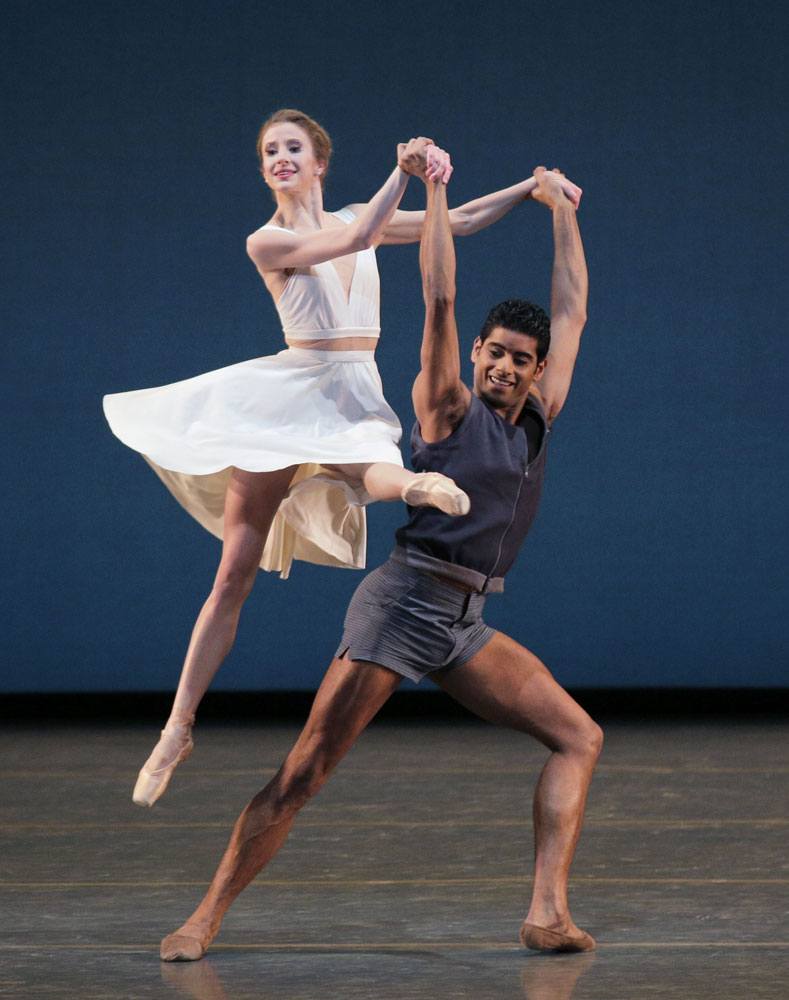

Though the ballet is mainly abstract, there are a few loose plot points, which enable the leads to stand out as characters. Tyler Peck, clad in a striking blue bathing suit, not only shows off her technical prowess, but also plays a girl with a delightful sense of spark and fun. Sterling Hyltin and Amar Ramasar, who portray lovebirds on the beach, contribute hints of maturity. It is not, however, the kind of maturity seen in La Jolla, where most of the population is retirees.

Peck’s need to display movement virtuosity overshadows any feeling or story he could have conveyed. For example, the dancers of the corps act more as design vehicles than real people, and the relationship between the in-love couple is more generic than illuminating or enchanting. Because of Peck’s focus on wowing with steps and speed, even the small allusions to narrative get muddled. At one point, Hyltin runs into the waves, created by the massing of the corps, and Ramasar follows her. It becomes unclear as to whether they are playing in the water, drowning, or dreaming the whole thing up. When the waves subside, the couple lays motionless as other dancers, who previously represented waves, fail to revive them. Seconds later, Hyltin and Ramasar get up and dance joyfully (and absurdly) away.

The most ingenious part of la Jolla is Peck’s depiction of waves, created by a group of dancers wearing shimmery blue tops and dancing on the upstage diagonal in swelling and receding patterns. Peck doesn’t revert to cliché arm waving or other overused water images. Instead, he has female dancers lie prone with their legs in the air while the men form complicated patterns of interlacing circles behind them. He choreographs other women to then weave under the men’s arms. This ensemble-created fluidity is mesmerizing. Other sections, however, don’t flow together quite as smoothly. There are multiple occasions when the dancers arrive into formation and then stand still, waiting for the next musical cue to launch them into the next movement phrase.

Peck’s ballet occurred in the middle of the evening’s program, following Alexei Ratmansky’s spatially stunning Concerto DSCH, and preceding Jerome Robbins’ groovy N.Y. Export: Opus Jazz. After seeing all three pieces, it became clear that Peck did a nice job showing off the dancers’ strengths. While Robbin’s Opus Jazz is a brilliantly created, timeless piece of fun that can, if danced well, be a masterpiece, many of the girls looked like they missed their pointe shoes and appeared uncomfortable moving their bodies outside of the ballet lexicon. While not very evocative of a true Southern Californian way of life, Paz de la Jolla was at least danced with great enthusiasm by Peck’s fellow dancers.

Cleo Person is a first year Dance Division student at The Juilliard School.