By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 10, 2014

MUNICH — Creative exhaustion appears to have arrived for a whimsical, multi-year promotional campaign here. Its subject: the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Its budget and goals: inscrutable. The thing would never have seen the light of day in the U.S., if only for legal reasons, and its existence is one of several signs of a vain administration within parent entity Bavarian Broadcasting, or Bayerischer Rundfunk, known as BR.

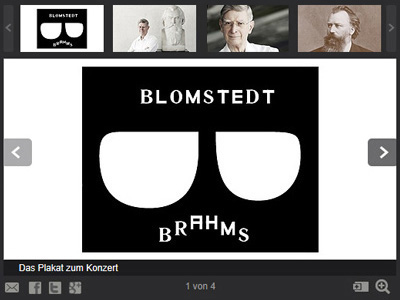

Centered on posters, or Plakate, the distinctive campaign eschews images and color and relies for its life on typography, specifically the manipulation of one clunky serif-and-sans-serif font, used until recently with flair. Typically, names or numbers related to a concert program are toyed with. Riccardo Muti comes to conduct, and so we see a giant MU. At some distance, not where spelling dictates, we land on the TI. Or RAT tops a Ligeti-Schumann-Haydn-Sibelius poster, its TLE completing the conductor’s name lower down. III, heavy like prison bars, blares out for a Bruckner Third Symphony.

The layouts show up on street posters, the Internet, handouts, even on the BRSO’s scholarly and free concert program books. They are the brainchildren of Bureau Mirko Borsche, whose trending design clients include Zeit Magazin, Harper’s Bazaar and the Bavarian State Opera.

But the design firm’s ideas have become less flattering of late. A gas mask promotes Herbert Blomstedt’s all-Brahms program this week (Feb. 13 and 14). In use for months already, the image results from a zoomed-in, weighty letter B, rotated right. The composer’s name forms a facial pout that traces the B’s dimple, with the conductor’s name straight, above the mask’s eyes. No slur is meant, one must assume. Other inverted or morbid layouts, including distorted initials, have dampened the aging campaign’s fun as options for novelty have narrowed.

Is there oversight? Only of the lightest kind, apparently. Beyond the posters, questions lurk about misleading buttons and missing contact information on the BRSO website, extravagant BRSO sales literature, and a peculiar organizational structure.

Orchestra administration is buried deep inside BR, a Munich-based, license-funded broadcaster with a budget above $1 billion and more on its plate than classical music. Just how deep is reflected on BR’s giant website, whose home page offers no direct link to the orchestra. Site visitors must learn that the acclaimed BRSO is part of BR Klassik, and then a link can be found. Once on the orchestra’s home* page, material is clearly presented. But not all of it. A click on “Presse” at the top, for instance, loops you back to BR and no fewer than sixteen press officers, one of whom, Detlef Klusak, has “Musik” after his name. In a brief call last week, however, Klusak confirmed he has nothing to do with the BRSO.

Finding the orchestra’s managers from its home* page is a trip in itself. You first click on “Orchester,” then on “Die komplette Besetzung” (the whole cast) under an illustration showing only musicians. You scroll down to the lower right corner of the next page, click on “Management,” select and copy the name of the person you want — there being no email addresses or phone numbers on the secluded page — and Google him or her!

Nikolaus Pont is in charge. New, with less than a year on the job, he did not initiate the promotional campaign or plan the website, and it isn’t clear yet whether he is more than a caretaker. (Fundraising, to be sure, is not front-and-center for him as it would be for an American counterpart.) Still, he must have reviewed the BRSO’s 2013–14 season brochure.

Or rather book. Weighing in at 1 lb. 6 oz. (more than half a kilogram), its 180 pages lie between thick, gloss-coated card and a cloth, die-embossed orange spine. Inside are concert details and color photographs, including four hopelessly sullen shots of Chefdirigent Mariss Jansons. Freely distributed, the Bureau Mirko Borsche-developed book carries no paid advertising. Broadcast-license-payers can only imagine its cost and the fees earned for design and printing.

An area optimistically labeled “Kommunikation” is headed by Peter Meisel, while another group has its own person under “Marketing.” Meisel works directly with the design firm (a Facebook favorite) but his diverse duties include photography, video liaison and special events. He is, moreover, tasked with keeping the world’s press (including this blog) informed of, and involved in, BRSO activities. A recent round-robin list showed 78 email contacts for the orchestra’s media outreach: 14 within BR, 9 at the Süddeutsche Zeitung (Bavaria’s answer to The New York Times), 16 at other Bavarian media outlets, 16 German outlets, 2 foreign (including Musical America), 6 German freelance music journalists, 2 non-media and 13 private.

Is it time for fresh approaches at the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra? By U.S. standards, certainly, on several fronts, starting with more management accessibility and a promotional campaign that respects visiting artists. As for this week’s concerts, Brahms will pout or smile depending on Blomstedt and the musicians, not on any poster design. The serene and sage maestro, still effective in his eighties, will no doubt laugh his gas mask right off, but of course that would suggest an altered formation for B-L-O-M-S-T-E-D-T.

[*Domain and site changes in April 2015 removed the awkwardness described here.]

Screenshot © Bayerischer Rundfunk

Related posts:

Zimerman Plays Munich

Jansons Extends at BR

Jansons! Petrenko! Gergiev!

BRSO Adopts Speedier Website

Blomstedt Blessings

Magelone-Romanzen on Disc

Monday, October 16th, 2017By ANDREW POWELL

Published: October 16, 2017

MUNICH — Sony has released a remarkable recording of Brahms’s Magelone-Romanzen, Op. 33, complete with Zwischentexte prepared by German author Martin Walser. Christian Gerhaher sings the fifteen songs and recites two of the other three poems (the 1st, 16th and 17th) from Ludwig Tieck’s 1797 narrative not set to music. Walser, 87 at the time of the recording, reads his own choice of eloquent, plain words, condensing Tieck’s eighteen-section prose while still advancing the tale and earmarking each song, as Brahms would have expected. Between the two of them, the German language has never sounded more beautiful. Gerold Huber accompanies. Sessions stretched over five days, at Bayerischer Rundfunk here, an indication of the care taken. This 93-minute, 2-CD release, with booklet essay and Romanze texts in German only, has EAN 088985 3110223 and ASIN B01NA7L2AN and must be distinguished from the widely reviewed single-disc issue omitting Walser’s work. Essential listening.

Images © StadtMuseum Bonn, 1865 wood engraving after a drawing (Brahms); 1838 oil on canvas by Joseph Karl Stieler (Tieck); Gregor Hohenberg (Gerhaher); Marion Koell (Huber); Philippe Matsas (Walser)

Related posts:

Fall Discs

Tutzing Returns to Brahms

Time for Schwetzingen

Liederabend with Hvorostovsky

Gergiev, Munich’s Mistake

Tags:Bayerischer Rundfunk, BR Klassik, Brahms, CD, Christian Gerhaher, Commentary, Die schöne Magelone, Gerold Huber, Kritik, Magelone-Romanzen, Martin Walser, Review, Sony Classical, Tieck

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed