By Rebecca Schmid

The Deutsche Oper maintains a dedicated West Berlin following not only for its provocative stagings but sober concert operas showcasing star singers. Of nine “premieres” this season, four are in concert, and in the best scenario feature works known for their dramaturgical weaknesses. The house claimed in a press conference last season that it turned to concerts because of a need to repair stage machinery, although the format has also occupied programming in the past. The renovation has since been delayed until next season (rumors about the house’s financial woes aside). Following a performance of Bizet’s Les Pêcheurs de Perles with Patricia Ciofi and Joseph Calleja in December, the company opened Verdi’s I Due Foscari on May 9 featuring Angela Meade in her Berlin debut alongside the tenor Ramon Vargas and the legendary baritone Leo Nucci.

Verdi’s sixth opera has struggled to meet with popular acceptance since its 1844 premiere in Rome, according to scholarly speculation because it followed on the heels of his more dramatically gripping Ernani. The composer himself wrote to his librettist Francesco Maria Piave early on that the work did not “possess the stage qualities that an opera demands,” particularly in the first act, and later admitted that the opera suffers from being too gloomy. The story centers upon a political struggle in fifteenth-century Venice in which Jacopo Foscari, son of the Doge Francesco Foscari, is falsely accused of murder by the Council of Ten. Despite the pleading of Jacopo’s wife Lucrezia, the Doge lawfully goes along with the orders decreed by council member Jacopo Loredano, a family rival, and his son is sent into permanent exile. Jacopo subsequently drops dead, and his father follows suit just after relinquishing power to the council.

Much in keeping with the apocalyptic tone, the score is an interesting study in the early use of Leitmotifs, which lends the opera ideally to a concert staging. A lamenting clarinet foreshadows Jacopo’s tragic fate already in the overture, subsequently appearing to usher in the character before several of his numbers. Verdi designates Lucrezia with a fiery series of rising triplets in the violins, while the Doge is assigned a ruminative motive in the celli and violas. Even the council is indicated with a recurrent procession of woodwinds. The opera closes in on the intimate, inter-personal relations between the main characters, launching from arioso to cabaletta to duetto while revolving around an overwhelmingly grief-stricken tone.

Vargas was not in his best voice for his opening cavatina “Dal più remoto esilio” but warmed up to prove himself as touching and vocally assured a Jacopo as one could hope for in the preghiera “Non maledirmi o prode” of the second act, in which he begs for mercy after being haunted by a ghost of another victim of Venetian law. He brought a great deal of tenderness to the following duetto sequence with Lucrezia (Meade), in which he declares that their suffering is worse than death, with the singers bringing their voluminous voices into fine chemistry with each other. Meade captured the distraught heroine with warm, powerful tone, sensitive dynamic shading and velvety legato that did justice to the emotional range of Verdi’s deceptively simple melodies. She initially belted out a couple of climatic high notes that were overwhelming in this house—this young spinto may be one of few singers who is truly destined to sing at the Met—but she found the right restraint in her romanza with the Doge (Nucci) in the first act, and the ease with which carried easily above full ensemble numbers was a delight.

Despite the fine performances of Vargas and Meade, it was Nucci who captured the soul of this opera most convincingly (at least for this listener). Though no longer in his prime, he has this role in his bones, evoking the authoritarian yet tortured nature of the Doge with diction and phrasing that threaten to be a lost art. His third act aria “Questa dunque è l’iniqua mercede,” in which he confronts the chorus about Jacopo’s innocence, consumed the audience in a sense of irreversible doom. Even when he grabbed his music stand upon Lucrezia’s announcement that Jacopo had died in exile, there was nothing forced about his performance. It takes an artist of this vintage to anchor a concert staging in which the audience only has the singers’ vocal and facial expression as dramatic reference.

The conductor Roberto Rizzi Brignoli also harnessed the orchestra of the Deutsche Oper, directly onstage behind the singers, to fine effect. While Les Pêcheurs de Perles had suffered from some untamed brass playing and steely phrasing under the young Spanish conductor Guillermo Garcia Calvo, Brignoli coaxed well-balanced, flexible lines, producing the most authentic Italianate inflections I have heard from this orchestra and never overwhelming the singers. The chorus of the Deutsche Oper lived up to its consistently excellent standards under director William Spaulding. The audience could not hold back its applause and “bravis” throughout the evening, an unequivocally warm response that contrasts sharply with the reception of the house’s Regietheater-prone premieres, although this was a particularly well-mannered, mostly retired crowd drawn from Berlin’s bourgeois boroughs.

Sick Peaches at HAU1

James Jorden, covering the Metropolitan Opera’s premiere of Anna Bolena on his blog Rough and Regie last fall, observed that lazy critics often veer toward the adjective “handsome, descriptive of any production that doesn’t feature actual vomit as a design element.” As I live one of the continental capitals of what could easily be designated as Eurotrash, I’ve been subjected to some pretty outlandish productions. But I never thought I’d ever see an actual simulation of vomit at the climactic moment of an opera. Then again, I did decide to go and see a production of Monteverdi’s Orfeo starring Peaches, a kind of underground post-modern Madonna whose sexually charged raps have designated her as Berlin’s notorious enfant terrible (at least according to a scathing review in the local paper Der Tagesspiegel). The opera was conceived for her in the title role at the HAU1 Theater in Kreuzberg, with preparation including a half-year of voice lessons and language coaching (the Canadian native had never sung opera and didn’t know a word of Italian). The production also featured an original Peaches ‘composition’ (read: rap) which she called “Sick Bitch,” and yes, she got sick at the end.

So much for preserving the innocence of what some consider the western world’s first opera (although it was really Jacopo Peri’s Euridice). Of course, it would be ridiculous to judge this wacko Orfeo, seen during its third run on May 4, through the lens of a real opera critic. The Tagesspiegel’s observation that the efforts to prepare Peaches for an opera “led to shockingly little”—calling her the production’s “big negative” rather than an asset—is posited on the idea that someone who has made a career as a punk rapper could learn to sing opera in six months and that the intention was to have her do so in the first place. The production featured a cast of young singers and the experimental chamber ensemble Kaleidoskop in the pit under Swedish conductor Olof Borman, but this Orfeo was above all a vehicle for Peaches to shock and provoke much as she does in her own acts.

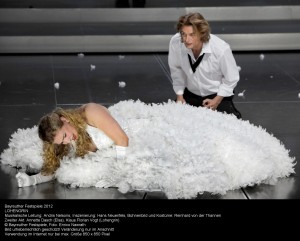

The opera is cut heavily and lasts under two hours. Apollo never appears, and the score includes a Lachenmann-esque composition by Timo Kreuser to represent the stark conditions of the underworld—an interesting idea in principle, but it is hard to make the argument for cutting Monteverdi in favor of this uninspired squealing and creaking. Monteverdi’s opening ritornello was played as the audience entered the theater, with some initially shabby bowing and phrasing but more finesse as it recurred sporadically after the entrance of Euridice catwalking as she poured pieces of styrofoam into a circle. Following the heroine’s aria “Io la musica son”—during which a banner of pithy anarchic precepts such as “no leader” and “screw in the streets” descends—she pulls Orfeo, Peaches, into the circle and strips her down to a skin-colored nylon suit.

The ensemble numbers quickly turn into orgies with heavy stroking; during “Qui le Napèe vezzose…Fu viste a coglier rose” (Here the charming wood nymphs…were seen picking roses), Peaches (who was wisely left out of the ensembles) tosses latex gloves onto the singers who are already in the process of tying each other up. The centerpiece of the staging (directed by Daniel Cramer and designed by Mascha Mazur) is a brown hut entitled “prospect cottage” that looks straight out of a kindergarten; it is here that Eurydice will be nursed from illness in the underworld. Surgical masks and an oxygen machine are necessary to survive. Peaches, descending with a lyre with chains for strings, breaks the spell with some electronically-modified chanting and her rap: “Hell’s hot/I’m getting a cold…” while Eurydice bops around in the background. Orfeo’s magical powers enable her to exorcise his (her?) lost beloved, manifested ever so elegantly with what I’ve described above.

The following ensemble number “E’ la virtute un raggio/Di celeste bellezza” (Virtue is a ray of celestial beauty) emerged like balsam to the senses, and indeed the musical quality of the actual classical musicians present had increasingly held its own. Ulrike Schwab was a coquettish Eurydice, with a pleasant lyric voice that probably would have been even more effective had she not been so consumed with the director’s instructions. The countertenor Armin Gramer, managing to elegantly pull off a tight, strapless gown, gave a stand-out performance as Speranza and in two other small roles. The mezzo Sabine Neumann warmed up by the second half to give a fine cameo of Proserpina. I won’t even bother criticizing Italian diction because there are simply too many areas where a critic could nitpick, not to mention the less than ideal acoustics of the theater. As far as Peaches’ attempts to sing opera, she was irritating at best with the exception of the opening lines of “Tu sei morta” upon losing Eurydice. She managed to convey some poignant emotion and carry a slightly legato tune, which was a relief after the rasping and muted shrieking to which she subjected her vocal chords throughout most of the evening.