BY Albert Innaurato

In John Elliot Gardiner’s Bach — Music in the Castle of Heaven there are some penetrating remarks about Henry Purcell. Ralph Vaughan Williams is buried right next to Purcell in Westminster Abby. Vaughan Williams and Sir Edward Elgar had ended the idea that Purcell was the final great English composer. And then, Benjamin Britten had donned the armor and waded into the cliche that England was “the land without music”.

At Downton Abbey they would have had some Elgar 78’s, perhaps. And in 50 Shades of Gray, the BDSM fantasy, mention is made of Thomas Tallis, a name connected with RVW. And goodness knows what Benjamin Britten might be connected with — some version of Larry Kramer’s play called The Abnormal Heart? But away from soaps and saddles, I realized it had been a long time since I had thought about Teddie (as Elgar liked his few intimates to call him) and RVW, and that 2013 had been the fiftieth anniversary of Ben’s death. My far less tactful self had written about the biographies and documentaries “investigating” Ben at

Benjamin Britten: THE BITTER WITHY – mrs john claggart’s sad life

but that’s because I love Britten despite the inevitable re-evaluation going on. Although not free of degrees of homophobia and horror (Ben was a pederast, probably not sexually active), some of it makes sense. I too am sorry Ben wrote so many operas. Yes, it was brave that he and the tenor, Peter Pears, lived as a couple, fairly openly, when all homosexual acts between men were criminal in England. Those who lament Ben’s vocal works when early masterpieces such as Variations on a Theme by Frank Bridge and the Berg besotted but powerful Sinfonia da Requiem, and the later, magnificent Cello Symphony and Third Quartet all demonstrate a heart stopping power might at least have a point worth arguing. However, the more radical assertion that the phenomenally productive Britten was “written out” after Peter Grimes in 1945 is ridiculous.

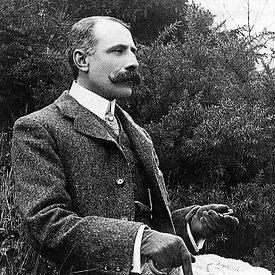

But I realized that I had never been interested in Elgar and knew only a little about him and Vaughan Williams. I read the compendious Edward Elgar: A creative Life by Jerrold Northrop Moore, the interesting Edward Elgar and his World by Byron Adams and Michael Kennedy’s responsible The Life of Elgar. I also looked at scores, thanks to the Great Central Library of Philadelphia and listened to what looked interesting.

There are many prominent worshipers of Elgar. but I must confess to thinking his life was more interesting than his music. I am unable to embrace the many religious choral works, though it’s true that Elgar is far more imaginative than his rivals, with remarkable textures and some risk taking (a shofar is blown at the start of the Dawn section of The Apostles and his use of tam-tam and other percussion to support it has remarkable atmosphere.) He also had a significant melodic gift and considerable theatrical flair. Britten recorded a perceptive, decidedly unsentimental Dream of Gerontius, Elgar’s masterpiece in this line. I wanted to stop the music long before the (lovely) end.

But surely The Enigma Variations, the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, and for many people the First Symphony are imposing? Elgar was primarily a melodist and a very gifted one; that’s not a problem in short pieces, but symphonic work needs an intellectual and harmonic construct that is clinching beyond whatever themes a composer spins.