By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 25, 2013

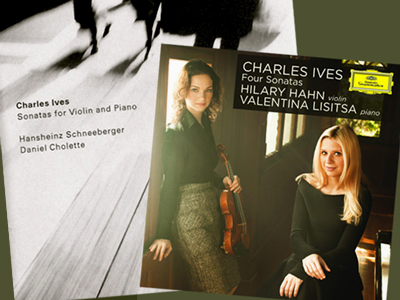

MUNICH — Hilary Hahn threw a spotlight recently on benchmark American chamber music: the four violin sonatas of Charles Ives. Fond of the Third Sonata (1914), she recorded the whole cycle for Universal Music Group in 2009, up the Hudson Valley accompanied by Internet pianist Valentina Lisitsa. The scores are probing, refined and intimate here, bold and sovereign of spirit there. They make an engaging group, and a lucid one: Ives’s propensity for throwing in the kitchen sink faces the agreeable constraint of two voices. The First Sonata (1908), at least, attests to Yankee genius.

But the highly touted CD from Hahn and Lisitsa is one of a dozen Ives cycles around and, it turns out, has not always the most to say. The discreet Munich label ECM Records, for instance, sells a 1995 traversal by violinist Hansheinz Schneeberger and pianist Daniel Cholette. To this recording, made near Heidelberg, the duo brought twenty years’ experience playing Ives, and Schneeberger, at 69, a certain éminence, having premiered violin concertos of Frank Martin and Bartók in the 1950s.

Not surprisingly, Hahn is at her most persuasive in the 1914 work. Its central Allegro lights up the Deutsche Grammophon disc, buoyed throughout by Lisitsa’s gutsy playing. The last movement, which Schneeberger and Cholette allow to turn saccharine, is saved by Hahn’s sense of purpose and cool clean manner. Similar qualities bring shape to the extended and ambitious first movement, where the ECM pair sparsely limp along.

Schneeberger and Cholette excel elsewhere. Their masterful First Sonata finds Ives’s lyrical and energetic impulses deftly balanced, and its Largo cantabile — affectionate, never precious — is traced with palpable American style. Here Hahn and Lisitsa sound cursory and the violin part wants more personality.

The Second and Fourth sonatas are shorter. The Second (1910) shares thematic material with the First; it is a more direct and perhaps lesser work than the other three despite the nostalgic labels on its movements. Schneeberger, and only he, makes an effort to present it in independent colors.

The concise, perplexing Fourth (1916) bears the title Children’s Day at the Camp Meeting. Ives began its composition with a child’s playing ability in mind but soon veered off in dark and tricky directions. Hahn and Lisitsa find the sonata’s lyricism but not much else. Schneeberger and Cholette adopt a painfully slow pace in the middle movement, famously marked Largo—Allegro con slugarocko, lending gravitas. Cholette is forceful here. The ECM musicians then bathe in irony the truncated last movement, with its reference to Shall We Gather At the River? Ambiguity reigns as the music trails off.

Alternative readings of the Ives cycle include: Rafael Druian, violin, and John Simms, piano, recorded in 1956 (Mercury); Paul Zukofsky and Gilbert Kalish, 1963 (Folkways); Zukofsky and Kalish again, 1972 (Nonesuch); Millard Taylor and Frank Glazer, 1975 (Vox); János Négyesy and Cornelius Cardew, 1976 (Thorofon); Daniel Stepner and John Kirkpatrick, 1981 (MHS); Gregory Fulkerson and Robert Shannon, 1988 (Bridge); Alexander Ross and Richard Zimdars, 1992 (Bay Cities); Curt Thompson and Rodney Waters, 1998 (Naxos); Nobu Wakabayashi and Thomas Wise, 1999 (Arte Nova); and Lisa Tipton and Adrienne Kim, 2004 (Capstone).

Photos © Edition Zeitgenössische Musik and © Universal Music Group

Related posts:

Volodos the German Romantic

MKO Powers Up

Plush Strings of Luxembourg

Pollini Seals His Beethoven

Zimerman Plays Munich