By ANDREW POWELL

Published: November 23, 2012

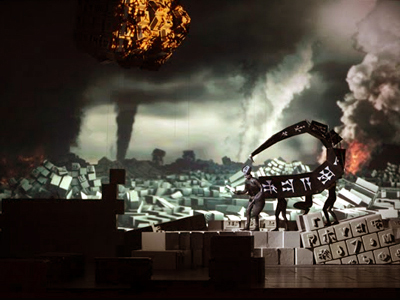

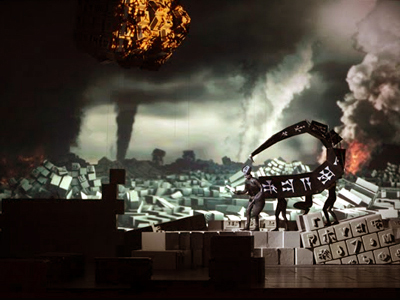

MUNICH — Scorpion-Man prowls the rubble of an unnamed flattened city at the start of Babylon, Jörg Widmann’s new opera, wailing as he moves. We should care.

Seven scenes, a Hanging Garden interlude, and three costly theater hours later, he is back, doing his thing over the same debris, also multiplying himself, and alas we have not cared or even learned what he represents. Perhaps he is us sad cityites, predatory and detached from our souls.

Widmann’s librettist for this Bavarian State Opera commission (heard and seen Oct. 31) is the post-humanist philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, whose worries, intra-urban and intra-galactic, drive Babylon in one big circle against the backdrop of the 6th-century-BC Jewish exile.

Sloterdijk’s narrative feebly pivots on a love-interest, in the persons of exile Tammu and local priestess Inanna. The character Soul is catalyst in a progression of these two that ends, before the circle has closed, in a concordance of Heaven and Earth (cue sweet music).

Along the way, Tammu gets drugged, laid, sacrificed, resurrected, and flown away with his gal in a spaceship. After administering the drug and enjoying her man, Inanna’s one job is to descend post-sacrifice into the Underworld and retrieve him, being sure not to lose sight of him as they make their way out together.

If this suggests a too-rich stew of Isolde or Norma and Euridice with Tamino, it is. But we are in Babylon, and your bowl arrives as the Euphrates overflows, the New Year rings in at the Tower of Babel, and Ezekiel dictates the Word of God, not to list the antics of seven Sloterdijk planets and fourteen Poulenc-ish sex organs.

Born here in 1973 and locally esteemed, Widmann as composer is much identified with Wolfgang Rihm, one among several teachers and influences. He is, besides, a bold and expressive clarinetist: a 2012 Salzburg Festival performance of Bartók’s Contrasts with Alexander Janiczek and András Schiff all but vaulted off the Mozarteum’s platform, and a 2011 Munich partnership with the Arcanto Quartet found rare vigor as well as cozy plushness in Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet.

The Nabucco-era subject had taken the composer’s fancy long ago. Ideas sprouted. A raucous Bavarian-Babylonian March emerged as orchestral fruit last year, bridging the millennia if not exactly the cultures. At some point came the link with Sloterdijk and the decision to plough forth with an opera, Widmann’s sixth piece for music-theater.

Undaunted by the librettist’s loony layers, Widmann supplies for Babylon music of chips and shards and sporadic mini-blocks. 160 minutes of it.

He savors direct quotes, splintered just past the point of identifiability. These he takes from jazz, operetta, lute song, Baroque dance, cabaret, Hollywood, symphonies, band repertory. He crafts brief, pleasingly original blocks of sound in various forms — brass swells, percussive glitter, choral refrains, woodwind banter — deploying them to varying effect. He is a gifted colorist, writing with virtuosity for all sections of the orchestra, in this case a large one, heavy on low winds and percussion.

Vocally the writing is less fluent, less confident. Abrupt ascents are a peculiarity. The tessitura of all three principal roles — Inanna, the Soul and Tammu — lies coincidentally high for each of the voice types (two sopranos and a tenor). Vocal lines are often aborted, mid-flight, again producing small blocks.

Widmann’s chipboard elements are arrayed in rapid indigestible sequences some of the time (Scene III’s orgy). Elsewhere, thin writing overstays its welcome or fails to develop in sync with the cosmic-Biblical scheme (Scene V) — the “prolix musical treatment” George Loomis noted in his review.

Enter Carlus Padrissa, the busy Spaniard known for constant stage movement. Hired to define and motivate the opera’s characters and unite the threads in text and score, Padrissa delivers, well, movement.

The gloomy arthropod’s rubble swiftly morphs into moveable letterpress type: Cuneiform, Katakana, Cyrillic, Hebrew — ah, Babel, the universal translator — to be piled up by mummers, piled down, carried off, brought on. Nearly incessantly. Flown and raised platforms support and transport sundry participants, some of them needed. Projected screen-saver lines depict the restless Waters of Babylon. Moving photographic images reveal holy verse, hell fire, a meteor (or ICBM) crashing to Earth. There is always plenty to watch.

Still, two problems dog Padrissa’s circus-like approach to opera, evident in his 2007–9 Valencia Ring and 2011 Munich Turandot: movement everywhere deprives the action of focus; and physical space required for upstage activities (open wings, as in ballet) deprives the singers of sound boards (in the form of sets) to reflect and project their voices. So it is with Babylon.

In the Turandot — due by chance for Internet streaming in its revival on Sunday (Nov. 25), here, and significant for the textual decision to end where Puccini ended — the voice-projection problem is addressed by having much of the principal singing occur drably near the stage apron.

In Babylon it is addressed with amplification*, subtly on the whole, though on Oct. 31 individual vocal lines resounded unnaturally at several moments.

Generalmusikdirektor Kent Nagano brought to the new opera his dual virtues of judicious tempos and attention to balances. The orchestra played compliantly, David Schultheiß working as poised and able concertmaster. Anna Prohaska and Claron McFadden coped deftly with the vocal stratosphere as Inanna and the Soul. Gabriele Schnaut brought rolling majesty to the Euphrates personified. Countertenor Kai Wessel exuded glum fortitude as Scorpion-Man. Jussi Myllys, the Tammu, relished having more to do than in his numerous recent Jaquinos, serving Widmann’s music earnestly. Willard White, as Priest-King and as Death, growled and boomed with his customary expertise.

When final blackness came, the polite Bavarian audience registered its ennui not with boos but with the barest, most ephemeral applause. Reconciling Heaven and Earth had proven easier than reaching across the proscenium.

[*Bavarian State Opera in a Nov. 26 message noted that “amplification was used for some parts” of the opera and that Widmann “actually marked the use of amplification for the scenes with heavy orchestral instrumentation in the score.”]

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Levit Plays Elmau

Petrenko Hosts Petrenko

Manon, Let’s Go

Tonhalle Lights Up the Beyond

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

![TOM1848[1]](http://www.musicalamerica.com/mablogs/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/TOM18481.jpg)

Maestro, 62, Outruns Players

Sunday, November 22nd, 2015By ANDREW POWELL

Published: November 22, 2015

MUNICH — At five o’clock last Sunday afternoon, Munich time, three Mariinsky Orchestras began to play. Two of them launched into Pikovaya dama and Die Zauberflöte at the Mariinsky complex in St Petersburg. The third, here at the Gasteig, opened the accompaniment to a witty Shchedrin vocalise. Such are the possibilities with a roster of 335 musicians, the world’s largest. At the concert, though, the Mariinsky name was bizarrely buried. “MPhil 360°,” screamed the program book cover, “das Festival der Münchner Philharmoniker,” nowhere mentioning the Russian orchestra. The missing credit no doubt mattered less to Valery Gergiev, who now helms both orchestras (or all four, depending on how you count), than the furthering of his new goals: to better relate the Munich Philharmonic to citizens of all walks of life and to programmatically “bridge … German and Russian orchestra culture.” And in this the first MPhil 360° went far, as a lobby- and hall-based three-day jamboree with interviews and attractively priced music in varied formats. Indeed Gergiev himself went far, conducting as festival climax on Sunday five hour-long, off-subscription concerts centered on the Prokofiev piano concertos. Nine hands of Herbert Schuch, Denis Matsuev, Behzod Abduraimov (pictured), Alexei Volodin and Olli Mustonen partnered him at 11, 1, 3, 5 and 7 o’clock, respectively, while scores by Haydn, Mozart, Weber, Reger, the Munich composers Hartmann and Widmann, besides the Munich-based Shchedrin, offered mostly pertinent, mostly Germanic counterforce.

Fortunately for the MPhil’s amenable Intendant, Paul Müller, the extravagant project, at least Sunday’s marathon part of it, proved a logistical and artistic success, even if attendance hovered at 50% of the Gasteig’s capacity. It may or may not have been smart to let the Russians do 60% of the work — assigning them the first two concerts in addition to the five o’clock and leaving less than two hours of music to the day’s titular heroes — but orchestral standards held up throughout as numerous manned Medici TV cameras rolled. As if conducting 300 minutes of music was not enough, Gergiev amiably stood through solo encores and was available for interview during the intermissions. Not incidentally, he dedicated all the concerts to victims of the Islamist murders in Paris.

Hearing five pianists emphasized the disparity of the concertos. The scoring of the compact D-flat-Major work (1912) favors the orchestra, which was dazzlingly unchecked in this performance so that Schuch’s fleet playing could not consistently be heard. Volodin’s sparkle and linear integrity in the left-hand Fourth Concerto (1931) could not overcome the perception, in context, of a drop in creativity in the writing; the pianist more fully advertised himself with a blistering account of the Precipitato from Prokofiev’s Sonata No. 7. Mustonen presented the first three movements of the madly insistent Fifth Concerto (1932) as a unit, with its Toccata a backstop on essentially percussive ideas. But he attempted a round open sound for many figures, quite divergent from, say, Ciani or Béroff. His Larghetto and Vivo offered unforced contrast.

The concertos from 1921 and 1923 fared best. Although Abduraimov’s light touch demanded cupped hands to the ears, he breezed fluently through Concerto No. 3, finding playfulness in its angularity, nonchalance in its lyricism. His reading had a crystalline quality underpinned by decisive, shapely phrasing in the left hand, qualities that rendered uncommon detail in the Variations. To the G-Minor Second Concerto, summit of Prokofiev’s work in this form, Matsuev brought power and evident consideration of its 32-minute arc. Robust rhythms, neatly accented quiet passages, a frame to justly billet the big cadenza, flashes of droll humor in the Intermezzo — and the pianist barely glanced at Gergiev, who took his cues where he could. As encore came Rachmaninoff’s picture etude The Sea and the Gulls, equally intense and played with command of the long line.

If support from the podium in the concertos wasn’t always sensitive, repertory choices elsewhere mostly played to Gergiev’s strengths. The day got off to an alert start with a technically fine performance of Prokofiev’s First Symphony (1917) from the Mariinsky Orchestra. Next came a real Classical symphony, Haydn’s Bear (1786), but this lacked elegance and, consequently, expressiveness. Weber’s Romanticism bookended the second concert and concerto. His Freischütz Overture (1821) benefitted from the maestro’s energy shots at vital moments; the 1841 Berlioz arrangement of his Invitation to the Dance shimmered transparently.

When the MPhil showed up at three o’clock, a closer rapport was apparent between conductor and players (versus two years ago). Reger’s harmonically alluring Vier Tondichtungen nach Böcklin (1913) showcased first the strings (in an Elgarian picture with chances for the concertmaster), then the refined winds, next the whole orchestra (in the duly macabre third tone poem, Die Toteninsel), and finally Munich’s percussion section (in an exuberant bacchanal colorfully scored).

Two hours later the Mariinsky musicians were back, still on superb form, for that vocalise, the episodic and folksy Tanya-Katya (2002) with creamy-toned lyric soprano Pelageya Kurennaya; Hartmann’s Suite from Simplicius Simplicissimus, assembled in 1957 from the revised version of his 1935 opera, in a lively, at times jazzy mix of styles relished especially by the principal trombone; the concerto with Volodin; and, wrapping up a long haul for them, Naughty Limericks, the gaudy 1963 Shchedrin piece, which poorly followed the Prokofiev but was loudly applauded in the presence of the elderly composer, a friend of Gergiev’s. The MPhil’s second concert began with Jörg Widmann’s raucous concert overture Con brio (2008), again unhelpfully programmed with Prokofiev. The composer-clarinetist then played, or rather milked, Mozart’s A-Major Concerto, K622, jumping about the stage like an excited six-year-old, before Mustonen walked on to conclude this engrossing, unrepeatable venture.

Photo © Andrea Huber

Related posts:

Salzburg Coda

Stravinsky On Autopilot

Manon, Let’s Go

Gergiev Undissuaded

Time for Schwetzingen

Tags:Alexei Volodin, Aufforderung zum Tanz, Behzod Abduraimov, Commentary, Denis Matsuev, Gasteig, Hartmann, Haydn, Herbert Schuch, Jörg Widmann, Mariinsky Orchestra, Mariinsky Theater, München, Münchner Philharmoniker, Munich, Munich Philharmonic, Naughty Limericks, Olli Mustonen, Pelageya Kurennaya, Prokofiev, Rachmaninoff, Reger, Review, Shchedrin, Valery Gergiev, Vier Tondichtungen nach Böcklin, Weber, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed