By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 3, 2016

MUNICH — Visiting orchestras cost more for concertgoers. But why exactly? Several factors govern ticket prices on tours, often mitigating each other, and all have a bearing this month as three orchestras from this city hit the road:

— Bavarian State Orchestra (BStO) with Kirill Petrenko, general music director

— Munich Philharmonic (MPhil) with Valery Gergiev, chief conductor

— Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO) with Daniel Harding, guest conductor

Here at home these orchestras cost as follows, sampling the top prices for a regular concert without subscriber discount: BStO in the National Theater, U.S. $78; MPhil in the Gasteig, $68; BRSO in the Herkulessaal, $73. Tickets in all price categories include bus and train fares to and from the venue within a 25-mile radius.

Government subsidy, at the federal, state, and in the MPhil’s case city levels, holds down prices to ensure that all Munich audiences can afford to attend. It does not necessarily vanish on tour, at least not within Europe.

For instance, at Berlin’s Musikfest this month, a six-hour drive from here, you would pay a reasonable and consistent top price of $100 for the visiting BStO, MPhil or BRSO, with subsidy applying both to the festival and, federally, to the three German orchestras.

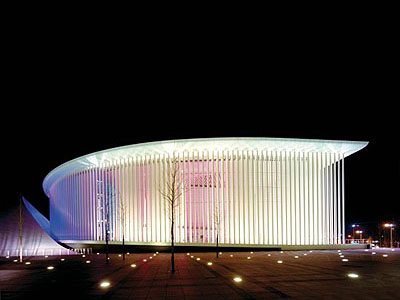

Lack of subsidy may seem to explain exorbitant prices at Lucerne’s Sommer-Festival in Switzerland. Or is a profit motive kicking in? Actually a third factor causes them: currency exchange and the robust Swiss franc. Lucerne, just four hours by road from Munich, wants $245 and $296 for the BStO and MPhil, respectively.

That last detail raises the issue of perceived worth. Why would Lucerne charge a premium for one Munich orchestra over another when Berlin prices all three equally? For that matter, why does Berlin ask more for visiting orchestras than for its own Konzerthaus-Orchester (at a $69 top, staying with the “regular concert without subscriber discount” benchmark) or Berlin Philharmonic ($84) when subsidy applies?

The concert presenter directly, and the concertgoer ultimately, places a value on an orchestra in part as a function of geography. In the small Swiss city but not in the German capital, Gergiev’s orchestra (or Gergiev) is valued more highly than Petrenko’s (or Petrenko). In Berlin, people are willing to pay more to hear out-of-town musicians, a flip side to familiarity breeding contempt.

Price-comparing assumes events have been priced to sell out, and sell out at roughly the same pace. Which in turn assumes presenters know their job. They may. But objectively the worth of an orchestra cannot rise or fall by the tour stop.

If beauty is in the ear of the beholder, the Milanese are more attuned than most. So say Teatro alla Scala’s managers by setting a top of $162 for the BStO’s concert there — far below Lucerne prices yet still double the tag at home. Low government funding in Italy helps shape their thinking, rather than any attempt to gouge, though it will make La Scala’s big platea hard to fill.

Otherwise prices vary against a mental cushion: presenters’ realistic belief that ticket buyers will allow for some unknown but fair travel expense being passed along to them, unaware whether such expense has been covered by grants. Traveling more widely than the other orchestras this time, the BStO costs $94 in Paris, $107 in Vienna and $117 in Luxembourg.

Back in Germany on dates in between those stops, the limited revenue potential of relatively small halls may explain BStO top prices in the range of $118 to $144 for Bonn, Dortmund and Frankfurt. Either that, or someone is profiting, an alien notion when the very existence of orchestras requires subsidy.

Presenters of visiting orchestras are indeed on occasion out to make money, just as they do with non-classical artists. NBS in Tokyo has been a world-renowned price-gouger. In Munich the busy presenter MünchenMusik often prices aggressively. There are several more.

What of three Munich orchestras touring at the same time? Music contracts here commonly run “Sept. 1 to Aug. 31,” with the summer months tail-ending the term ostensibly to provide time off. In practice this structure brings chances to earn extra income at festivals instead. September becomes an odd month: the musicians need a break and audiences are sated from summer performances; the main season is supposed to start yet nobody wants to get down to it. So a window opens for touring.

Photo © KKL Luzern Management AG

Related posts:

Concert Hall Design Chosen

A Complete Frau, at Last

Mastersingers’ Depression

Netrebko, Barcellona in Aida

Portraits For a Theater

Concert Price Check

Saturday, September 3rd, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 3, 2016

MUNICH — Visiting orchestras cost more for concertgoers. But why exactly? Several factors govern ticket prices on tours, often mitigating each other, and all have a bearing this month as three orchestras from this city hit the road:

— Bavarian State Orchestra (BStO) with Kirill Petrenko, general music director

— Munich Philharmonic (MPhil) with Valery Gergiev, chief conductor

— Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO) with Daniel Harding, guest conductor

Here at home these orchestras cost as follows, sampling the top prices for a regular concert without subscriber discount: BStO in the National Theater, U.S. $78; MPhil in the Gasteig, $68; BRSO in the Herkulessaal, $73. Tickets in all price categories include bus and train fares to and from the venue within a 25-mile radius.

Government subsidy, at the federal, state, and in the MPhil’s case city levels, holds down prices to ensure that all Munich audiences can afford to attend. It does not necessarily vanish on tour, at least not within Europe.

For instance, at Berlin’s Musikfest this month, a six-hour drive from here, you would pay a reasonable and consistent top price of $100 for the visiting BStO, MPhil or BRSO, with subsidy applying both to the festival and, federally, to the three German orchestras.

Lack of subsidy may seem to explain exorbitant prices at Lucerne’s Sommer-Festival in Switzerland. Or is a profit motive kicking in? Actually a third factor causes them: currency exchange and the robust Swiss franc. Lucerne, just four hours by road from Munich, wants $245 and $296 for the BStO and MPhil, respectively.

That last detail raises the issue of perceived worth. Why would Lucerne charge a premium for one Munich orchestra over another when Berlin prices all three equally? For that matter, why does Berlin ask more for visiting orchestras than for its own Konzerthaus-Orchester (at a $69 top, staying with the “regular concert without subscriber discount” benchmark) or Berlin Philharmonic ($84) when subsidy applies?

The concert presenter directly, and the concertgoer ultimately, places a value on an orchestra in part as a function of geography. In the small Swiss city but not in the German capital, Gergiev’s orchestra (or Gergiev) is valued more highly than Petrenko’s (or Petrenko). In Berlin, people are willing to pay more to hear out-of-town musicians, a flip side to familiarity breeding contempt.

Price-comparing assumes events have been priced to sell out, and sell out at roughly the same pace. Which in turn assumes presenters know their job. They may. But objectively the worth of an orchestra cannot rise or fall by the tour stop.

If beauty is in the ear of the beholder, the Milanese are more attuned than most. So say Teatro alla Scala’s managers by setting a top of $162 for the BStO’s concert there — far below Lucerne prices yet still double the tag at home. Low government funding in Italy helps shape their thinking, rather than any attempt to gouge, though it will make La Scala’s big platea hard to fill.

Otherwise prices vary against a mental cushion: presenters’ realistic belief that ticket buyers will allow for some unknown but fair travel expense being passed along to them, unaware whether such expense has been covered by grants. Traveling more widely than the other orchestras this time, the BStO costs $94 in Paris, $107 in Vienna and $117 in Luxembourg.

Back in Germany on dates in between those stops, the limited revenue potential of relatively small halls may explain BStO top prices in the range of $118 to $144 for Bonn, Dortmund and Frankfurt. Either that, or someone is profiting, an alien notion when the very existence of orchestras requires subsidy.

Presenters of visiting orchestras are indeed on occasion out to make money, just as they do with non-classical artists. NBS in Tokyo has been a world-renowned price-gouger. In Munich the busy presenter MünchenMusik often prices aggressively. There are several more.

What of three Munich orchestras touring at the same time? Music contracts here commonly run “Sept. 1 to Aug. 31,” with the summer months tail-ending the term ostensibly to provide time off. In practice this structure brings chances to earn extra income at festivals instead. September becomes an odd month: the musicians need a break and audiences are sated from summer performances; the main season is supposed to start yet nobody wants to get down to it. So a window opens for touring.

Photo © KKL Luzern Management AG

Related posts:

Concert Hall Design Chosen

A Complete Frau, at Last

Mastersingers’ Depression

Netrebko, Barcellona in Aida

Portraits For a Theater

Tags:Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Berlin, Bonn, Commentary, Daniel Harding, Dortmund, Frankfurt, Gasteig, Herkulessaal, Kirill Petrenko, KKL, Lucerne, Luxembourg, Luzern, Milan, München, MünchenMusik, Münchner Philharmoniker, Munich, Munich Philharmonic, Musikfest Berlin, National Theater, NBS, Paris, Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Teatro alla Scala, Valery Gergiev

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed