By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 22, 2017

MUNICH — Bavarian State Opera had a delicate problem. It was selling too many tickets online, more with each passing season. Its system, powered by CTS Eventim, was so robust and so fast that little was left to sell via phone or in person minutes after the 10 a.m. start time on heavy-demand days, causing embarrassment and a sense of unfairness inside its bricks-and-mortar box office, the Tageskasse, off chic Maximilianstraße.

No longer. This season, Germany’s busiest, richest, starriest and arguably best-managed opera company has a cure, one to make any Luddite proud. It does not smash the machines exactly. It instead decries the good system behind them and handicaps the online buyers who use them — seriously, unpredictably, before breakfast. BStO seats below €100 when Anja Harteros or Jonas Kaufmann sing are now all but inaccessible online.

“CTS Eventim’s system sometimes was not up for the amount of people trying to get tickets,” the company claimed in a late-January statement, and buying was “a bit of a lottery.” The system “would throw you out of the purchase process before ending it, which was acceptable neither for the Staatsoper nor for our audience.” Imagine. Computers that sell 100 million tickets annually for 180,000 events get the jitters handling Anja or Jonas.

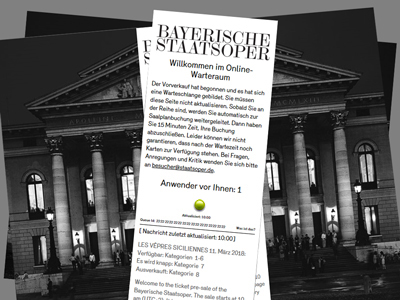

These flaws and a desire “to make the system more stable,” BStO’s story goes, led to its decision last fall to handicap online buying on certain mornings in 2016–17. How? A delay is “activated” when events in heavy demand go on sale, postponing the moment the buyer “gets access” to the online box office, called in German the Webshop (or occasionally Onlineshop). Phone and in-person selling, meanwhile, proceed as usual from the 10 a.m. start time.

Understandably the opera company has never announced the handicapping, and sources familiar with the Tageskasse scene say CTS Eventim’s system had nothing to do with the decision. The real motive, according to these sources, is to try to replicate online the speed of the physical line (queue) at the Tageskasse following years of grumbling from people who buy that way, and from staff too. A tug-of-war between Internet users and the bricks-and-mortar crowd has accordingly shifted in favor of the latter.

Out-of-town buyers are the worst hit, having fewer routes to tickets. Bavarians resident outside their capital city — it is the “state” opera after all — and fans of the renowned company as far away as East Asia and North America greatly rely on the Webshop.

The disadvantage is not new at BStO. Indeed the artificial online delays effectively bring to the main season the same narrow price availability for out-of-towners they have long experienced with BStO’s 142-year-old summer Munich Opera Festival. Tickets for the festival are first sold in snowy January in person only, and the lower four of eight price categories — roughly, seats below €100 for major performances — sell out this way when the biggest stars are scheduled, months before online ticketing starts.

Countless customers were surprised by the handicap on Jan. 12, 14, 18, 22, 30 and Feb. 2 while trying to buy tickets for Philipp Stölzl’s new production of Andrea Chénier, due March 12 and starring — gosh — both Harteros and Kaufmann. All performances were affected on those selling mornings, corresponding to BStO’s two-month lead time.

Surprised, and confused actually. The handicap throws up two screens in place of the Webshop. First, a countdown page, labeled with the quaint metaphor “waiting room” to dupe people into thinking the system is too burdened to process their order. This assigns a wait number, which ironically turns out to be far from “stable.” Then comes a standby page, for buyers whose number has dropped to 0 (zero) before the Webshop opens, i.e. before 10 a.m. — a strange situation, one might think, but the only one with potential to yield broad ticket choice.

Not-so-hypothetical scenarios:

| |

A in Augsburg

Unaware of the handicap, she logs on at 9:55 a.m. She faces not her expected Webshop but the countdown page. (She would be there regardless of what event and date she is pursuing. The whole operation is impacted that morning because one heavy-demand performance is going on sale.)

She has of course no idea when the handicap was activated. (The answer could be 6 a.m., about when a physical line might start outside the Tageskasse.) But she is less troubled than buyers who may have purposefully stopped work in Tokyo or climbed out of bed in Boston.

She sees 29 lines of precise instructions auf Deutsch, unless she has opted for English screens, in which case she sees a remarkably compressed version of just five lines. (The complete English is here.) Key instruction: “Do not refresh.” Below, she reads her wait number: a high one, 400. Her chances are nil, but she doesn’t know this. She ties herself up for an hour before learning. |

| |

N in Nuremberg

Logs on at 5:55 a.m. She is too early and goes straight into the normally functioning Webshop. She assumes she can just wait there until 10 a.m. But no. She must refresh the screen every twelve minutes or be disabled for inactivity. No instructions say this because the system was in normal mode when she entered. (To see them, she would have had to arrive via the countdown page and witness her wait number drop to 0 before 10 a.m.)

When she casually returns to the screen at 9:30 a.m., she discovers the Webshop inactive for her. She reloads. Now she is on the countdown page with number 200. Again no chance. |

| |

R in Regensburg

Fares better. He logs on at 6:15 a.m., apparently just after the handicap was activated. He lands on the countdown page with number 10. Like A, he is told not to refresh. He obeys. Later, but before 10 a.m., his number drops to 9, then 7. He wonders how this could be. No orders are being processed. (Possible answer: people on the standby page are failing to refresh and losing their place.)

But for him to succeed, his number must drop to 0 by 10 a.m. Otherwise, whether he’s at 400 or 4, he will be stuck on the countdown page during the crucial initial selling minutes.

Luckily he does drop to 0. He is moved to the standby page, a promising but precarious place. There he sees the instruction to refresh that N missed. He must do this every twelve minutes until 10 a.m. If he has arrived on the standby page early, say at 7:15 a.m., he will be doing a lot of refreshing. Should he fail — just once — he will find himself back on the countdown page holding a high number. (Anja and Jonas never wanted it that way.)

When the hour rolls around and the handicap ends, he must be ready, as in the past, to point and click with decisiveness and accuracy. His seats are secure only when they appear in his Einkaufswagen, the shopping cart. |

A, N, and R may be imagined. The following numbers are real, recorded during the Jan. 18 handicap on Andrea Chénier ticketing in checks using two browsers and two connections:

Logging on at 10:24 a.m., a wait number of 688 with 170 seats left to sell. Three minutes later, wait number 346 with 130 seat left. At 10:43 a.m., number 179 with 38 seats. At 10:54 a.m., number 40 with 19 seats. After another five minutes, access to the Webshop with 4 seats shown as available. By 11:04 a.m., 2 seats left but neither one of them moveable into the shopping cart. At 11:07 a.m., sold out, Ausverkauft. Despite this, a new buyer could log on at 11:10 a.m. and receive wait number 382, which would drop to 0 six minutes later and lead to an empty Webshop.

Bavarian State Opera should end this nonsense. The company is damaging its reputation and working against its own carefully evolved ticket structure and sales procedures, designed to draw people of all income levels from a broad geography.

Those procedures sell tickets three ways: subscription; single-event by written order; and single-event by immediate fulfillment. The latter two are processed on a staggered basis according to performance date. Written orders (traditional mail, fax, email) are worked three months out. Immediate-fulfillment sales (online, phone, physical presence in the Tageskasse) begin two months out.

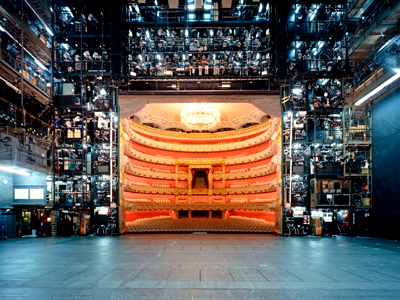

Each single-event method draws on fixed set-asides, or Kontingente, of seats in the 2,100-seat National Theater. These are broken down across BStO’s eight price categories and to within specific seating blocks, to as few as two seats, allowing near-total price and seat choice for each method. Quite sophisticated. And really quite fair, at least in the case of written orders. Even without handicapping, though, buyers outside Munich have less access to the immediate-fulfillment set-asides: getting to the Tageskasse may not be possible, and phoning is hard when there is heavy demand. Naturally they depend on the Webshop — and their hot connections, firm wrists, pinched fingertips and nanosecond nerves.

CTS Eventim, far from warranting criticism, could be held up as a most capable and user-friendly ticketer. Certainly its system offers an easier buyer interface, more precise seat sectioning, and lower fees, than that of the larcenous near-monopoly Stateside.

Instead of blaming its vendor, the opera company needs to go back to the future and solve its delicate Tageskasse problem with rigor and honesty. This means two things: adjustments to the Kontingente to reasonably protect in-person buyers; and an announcement of the change. Any tactic resulting in Internet screens that mislead buyers and waste their time, or too weird to spell out in a news release, is a bad one.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Staatsoper Imposes Queue-it

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Antonini Works Alcina’s Magic

Portraits For a Theater

Staatsoper Objects to Report

Tags:Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Commentary, CTS Eventim, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, News

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Saturday, September 3rd, 2016

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 3, 2016

MUNICH — Visiting orchestras cost more for concertgoers. But why exactly? Several factors govern ticket prices on tours, often mitigating each other, and all have a bearing this month as three orchestras from this city hit the road:

— Bavarian State Orchestra (BStO) with Kirill Petrenko, general music director

— Munich Philharmonic (MPhil) with Valery Gergiev, chief conductor

— Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO) with Daniel Harding, guest conductor

Here at home these orchestras cost as follows, sampling the top prices for a regular concert without subscriber discount: BStO in the National Theater, U.S. $78; MPhil in the Gasteig, $68; BRSO in the Herkulessaal, $73. Tickets in all price categories include bus and train fares to and from the venue within a 25-mile radius.

Government subsidy, at the federal, state, and in the MPhil’s case city levels, holds down prices to ensure that all Munich audiences can afford to attend. It does not necessarily vanish on tour, at least not within Europe.

For instance, at Berlin’s Musikfest this month, a six-hour drive from here, you would pay a reasonable and consistent top price of $100 for the visiting BStO, MPhil or BRSO, with subsidy applying both to the festival and, federally, to the three German orchestras.

Lack of subsidy may seem to explain exorbitant prices at Lucerne’s Sommer-Festival in Switzerland. Or is a profit motive kicking in? Actually a third factor causes them: currency exchange and the robust Swiss franc. Lucerne, just four hours by road from Munich, wants $245 and $296 for the BStO and MPhil, respectively.

That last detail raises the issue of perceived worth. Why would Lucerne charge a premium for one Munich orchestra over another when Berlin prices all three equally? For that matter, why does Berlin ask more for visiting orchestras than for its own Konzerthaus-Orchester (at a $69 top, staying with the “regular concert without subscriber discount” benchmark) or Berlin Philharmonic ($84) when subsidy applies?

The concert presenter directly, and the concertgoer ultimately, places a value on an orchestra in part as a function of geography. In the small Swiss city but not in the German capital, Gergiev’s orchestra (or Gergiev) is valued more highly than Petrenko’s (or Petrenko). In Berlin, people are willing to pay more to hear out-of-town musicians, a flip side to familiarity breeding contempt.

Price-comparing assumes events have been priced to sell out, and sell out at roughly the same pace. Which in turn assumes presenters know their job. They may. But objectively the worth of an orchestra cannot rise or fall by the tour stop.

If beauty is in the ear of the beholder, the Milanese are more attuned than most. So say Teatro alla Scala’s managers by setting a top of $162 for the BStO’s concert there — far below Lucerne prices yet still double the tag at home. Low government funding in Italy helps shape their thinking, rather than any attempt to gouge, though it will make La Scala’s big platea hard to fill.

Otherwise prices vary against a mental cushion: presenters’ realistic belief that ticket buyers will allow for some unknown but fair travel expense being passed along to them, unaware whether such expense has been covered by grants. Traveling more widely than the other orchestras this time, the BStO costs $94 in Paris, $107 in Vienna and $117 in Luxembourg.

Back in Germany on dates in between those stops, the limited revenue potential of relatively small halls may explain BStO top prices in the range of $118 to $144 for Bonn, Dortmund and Frankfurt. Either that, or someone is profiting, an alien notion when the very existence of orchestras requires subsidy.

Presenters of visiting orchestras are indeed on occasion out to make money, just as they do with non-classical artists. NBS in Tokyo has been a world-renowned price-gouger. In Munich the busy presenter MünchenMusik often prices aggressively. There are several more.

What of three Munich orchestras touring at the same time? Music contracts here commonly run “Sept. 1 to Aug. 31,” with the summer months tail-ending the term ostensibly to provide time off. In practice this structure brings chances to earn extra income at festivals instead. September becomes an odd month: the musicians need a break and audiences are sated from summer performances; the main season is supposed to start yet nobody wants to get down to it. So a window opens for touring.

Photo © KKL Luzern Management AG

Related posts:

Concert Hall Design Chosen

A Complete Frau, at Last

Mastersingers’ Depression

Netrebko, Barcellona in Aida

Portraits For a Theater

Tags:Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Berlin, Bonn, Commentary, Daniel Harding, Dortmund, Frankfurt, Gasteig, Herkulessaal, Kirill Petrenko, KKL, Lucerne, Luxembourg, Luzern, Milan, München, MünchenMusik, Münchner Philharmoniker, Munich, Munich Philharmonic, Musikfest Berlin, National Theater, NBS, Paris, Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Teatro alla Scala, Valery Gergiev

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Sunday, July 17th, 2016

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: July 17, 2016

MUNICH — When Anja Harteros was singing her first Toscas three seasons ago, it was clear she had the vocal resources for the role, and the Mediterranean temperament. Even so, the portrayal didn’t quite compute.

Enter Bryn Terfel, a Scarpia to rattle the aloofest, longest-legged of prima donnas. And Jonas Kaufmann, trusted stage buddy, sweet Cavaradossi. Now the diva’s doubt, fear, passion and rage turn on the instant, her slashing knife grip extending a ferrous will.

Harteros fairly lived the part July 1 here at the National Theater, teamed as she must have wanted and apparently undeterred by Luc Bondy’s clunky 2009 stage conception. Warm chest tones and creamy highs, floated or hurled, came into thrilling dramatic focus this time around. Illica and Giacosa’s words made inexorable sense, the Attavanti canvas and Terfel’s guts sure targets.

The tenor, too, had a great night: astutely colored phrases, gleaming top notes, a clarion but unexaggerated Vittoria! For once, E lucevan le stelle emerged as spontaneous thought, always in Kaufmann’s wonderfully lucid Italian.

If the mighty Welshman sounded a smidgen less opulent of voice than in previous Munich Scarpias, his characterization was as potent as ever, and his savoring of Puccini’s lines most enjoyable.

The snag, alas, was Kirill Petrenko’s conducting. Forceful and weighty, it never felt rooted in the language it was supposedly driving. Still, a terrific night for the Munich Opera Festival, and nowhere more refined than during Io de’ sospiri as sung by the Tölzer Knabenchor’s uncredited soloist.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Manon, Let’s Go

Tonhalle Lights Up the Beyond

Busy Week

Time for Schwetzingen

Schultheiß Savors the Dvořák

Tags:Anja Harteros, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bondy, Giacomo Puccini, Kaufmann, Kirill Petrenko, Kritik, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Review, Terfel, Tölzer Knabenchor, Tosca

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Tuesday, May 17th, 2016

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: May 17, 2016

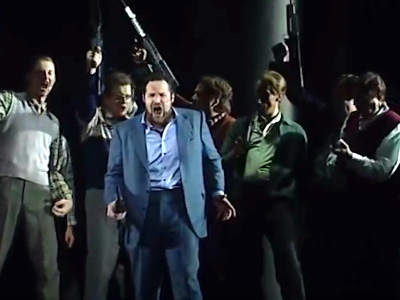

MUNICH — Beckmesser blew his brains out at the end of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg last night here in the Nationaltheater. That was after first aiming his gun at the back of the head of Sachs, and after a graphically brutal beating by David and bat-wielding apprentices had left him in a wheelchair — a predicament from which he had miraculously recovered, back onto his feet, within the few hours separating Johannisnacht and Johannisfest. Sachs, for his part, never saw the gun; he was sitting moping because Stolzing had ignored his Verachtet mir die Meister nicht, had declined to honor German art or the masters safeguarding it, and had simply walked out with Pogner’s prized daughter.

Whether Beckmesser’s character is of the suicidal type is a fair, though in context minor, question. Stage director David Bösch’s new production for Bavarian State Opera offers an altogether transformed view of Wagner’s erstwhile comedy, funded by the same hardworking Bavarian people who brought you the first, on June 21, 1868, when Hans von Bülow occupied GMD Kirill Petrenko’s podium.

Swiss-trained Bösch explores the role art can play in society by winding the clock in the opposite direction from the composer. Instead of reaching back three centuries to show the art-guild tradition at its liveliest, when Nuremberg prospered, he forwards us to a faceless town that has seen better days, where the institution feted by Wagner is in yet more jeopardy than when the score was written and where the masters in their trades suffer the effects of debilitating, distant economic forces. Somewhat outside these problems is the presumably flush Stolzing, but even he cannot invigorate through his candidacy a guild whose masters find it easier to delude themselves than honestly confront demise. Sachs’s Wahnmonolog fits right in. Not much else does.

The idea of collective depression finds little use for such musical-dramatic particulars as the scent of the Flieder (lilac) or the shade of the Linde (basswood). Bösch has to invert the humor in, for instance, the Nachtwächter’s round and Sachs’s gift to Beckmesser. He defies Wagner’s time-of-day and lighting directives. Indeed, clashes with the composer create an uneasy mix of narrative, pomp, violence and slapstick (song-trial errors marked via shocks to the applicant in an electric chair; a town-clerk serenade from atop a scissor-lift, constantly raised and lowered by the cobbler).

But Bösch’s own visual-stylistic trademarks are firmly in place, reminding us of his spacy, zoned-out previous work for this company: L’elisir d’amore (2009), Mitridate, rè di Ponto (2011), and, his touching flower-power effort, La favola d’Orfeo (2014). Neatly arranged decay, locally lit props, black limbo backgrounds, a funky insouciance to the stage action: these are some.

The Bavarian State Opera Chorus sang magnificently for this premiere, achieving levels of expressive detail and shading it reserves for its obsessive GMD; Sören Eckhoff did the coaching. Sara Jakubiak from Bay City, MI, made a welcome debut as Eva, acting well and producing girlish tones in mostly clear German. Benjamin Bruns coped sweetly with the boisterous lyric challenges of David. Jonas Kaufmann added the quality of heroic delivery to the youthful ardor and Lied skills evident in his Scottish Stolzing of long ago. Wolfgang Koch, vocally opulent, looked sloppy as Sachs but conveyed enlightenment anyway. He projected his words impeccably and never forced for volume. Markus Eiche’s musically ideal Beckmesser deserved and received the loudest applause, after tough toiling in Bösch’s action. Christof Fischesser intoned nobly and richly through Pogner’s wide vocal range, while the Nachtwächter’s chant seemed all too short as securely phrased by Tareq Nazmi.

Petrenko drew playing of color and sparkle from his Bavarian State Orchestra, favoring momentum (78’ 58’ 70’ 42’) over reflection but pointing the rhythms with ceaseless energy and emphasis, much to the opera’s advantage. Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg will be streamed as video over the Internet at 5 p.m., Munich time, on July 31, 2016, under sponsorship from Linde.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

See-Through Lulu

Time for Schwetzingen

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

Mariotti North of the Alps

MKO Powers Up

Tags:Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerischer Staatsopernchor, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Benjamin Bruns, Christof Fischesser, David Bösch, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Kaufmann, Kirill Petrenko, Kritik, Markus Eiche, München, Munich, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Review, Sara Jakubiak, Sören Eckhoff, Tareq Nazmi, Wolfgang Koch

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Wednesday, September 23rd, 2015

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 23, 2015

MUNICH — Post is under revision.

Still image from video © Bayerische Staatsoper

Related posts:

Nitrates In the Canapés

Muti the Publisher

Honeck Honors Strauss

Kušej Saps Verdi’s Forza

Time for Schwetzingen

Tags:Amanda Forsythe, Andrew Foster-Williams, Antonino Fogliani, Antonio Pappano, Antú Romero Nunes, Bad Wildbad, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bongiovanni, Bryan Hymel, Camerata Bach Chor Poznań, CD, Commentary, Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Damiano Michieletto, Dan Ettinger, Decca, DVD, Evgeniya Sotnikova, Gerald Finley, Graham Vick, Guillaume Tell, Günther Groissböck, Jochen Schönleber, John Osborn, Juan Diego Flórez, Judith Howarth, Kritik, Luca Tittoto, Malin Byström, Marina Rebeka, Michael Spyres, Michael Volle, Michele Mariotti, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Naxos, Nicola Alaimo, Nicolas Courjal, Opus Arte, Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Pesaro, Raffaele Facciolà, Review, Rossini, Rossini Opera Festival, Royal Opera House, Sofia Fomina, Tara Stafford, Virtuosi Brunenses

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Saturday, December 13th, 2014

By ANDREW POWELL

Published: December 13, 2014

MUNICH — Passive accompanist and intent visionary: Gianandrea Noseda managed to be both Nov. 18 in his debut program with the busy Bavarian State Orchestra. For Dvořák’s Violin Concerto (1879) he indulged David Schultheiß in a lyrical reading that generally took its time, ignoring chances in the outer movements to drive rhythms more forcefully. The soloist (and first concertmaster) worked without ostentation. He phrased exquisitely, made the countless dances dance, and clearly relished the supply of melody, presenting the work as a confident if mostly tranquil whole. Fine woodwind contributions brightened the proceedings.

Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony (1907) followed the break at this Akademiekonzert in the orchestra’s ornate crimson home, the National Theater. Now Noseda was in his element, revealing obvious enthusiasm and instinct for the music. Conducting from a pocket-book score, he made these opera musicians sound as if they played Rachmaninoff every week, quashing notions that their mixed schedule prevents adequate rehearsal for concerts. He found ideal balances between the strings and winds, apparently with ease. He allowed partial themes to fall naturally in place, climaxes to build themselves, and unity to emerge through gentle emphasis on material shared between the movements. He injected little dashes of suspense, pounced on and relished each accelerando. But he never overplayed his hand. It was a richly executed performance, urgent in the second movement, duly rapturous in the Adagio, and nowhere identifiable as the interpretation of a non-Russian.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Horn Trios in Church

Benjamin and Aimard

Concert Hall Design Chosen

Thielemann’s Rosenkavalier

Kaufmann, Wife Separate

Tags:Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, David Schultheiß, Gianandrea Noseda, München, Munich, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Rachmaninoff, Review

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Staatsoper Favors Local Fans

Wednesday, February 22nd, 2017By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 22, 2017

MUNICH — Bavarian State Opera had a delicate problem. It was selling too many tickets online, more with each passing season. Its system, powered by CTS Eventim, was so robust and so fast that little was left to sell via phone or in person minutes after the 10 a.m. start time on heavy-demand days, causing embarrassment and a sense of unfairness inside its bricks-and-mortar box office, the Tageskasse, off chic Maximilianstraße.

No longer. This season, Germany’s busiest, richest, starriest and arguably best-managed opera company has a cure, one to make any Luddite proud. It does not smash the machines exactly. It instead decries the good system behind them and handicaps the online buyers who use them — seriously, unpredictably, before breakfast. BStO seats below €100 when Anja Harteros or Jonas Kaufmann sing are now all but inaccessible online.

“CTS Eventim’s system sometimes was not up for the amount of people trying to get tickets,” the company claimed in a late-January statement, and buying was “a bit of a lottery.” The system “would throw you out of the purchase process before ending it, which was acceptable neither for the Staatsoper nor for our audience.” Imagine. Computers that sell 100 million tickets annually for 180,000 events get the jitters handling Anja or Jonas.

These flaws and a desire “to make the system more stable,” BStO’s story goes, led to its decision last fall to handicap online buying on certain mornings in 2016–17. How? A delay is “activated” when events in heavy demand go on sale, postponing the moment the buyer “gets access” to the online box office, called in German the Webshop (or occasionally Onlineshop). Phone and in-person selling, meanwhile, proceed as usual from the 10 a.m. start time.

Understandably the opera company has never announced the handicapping, and sources familiar with the Tageskasse scene say CTS Eventim’s system had nothing to do with the decision. The real motive, according to these sources, is to try to replicate online the speed of the physical line (queue) at the Tageskasse following years of grumbling from people who buy that way, and from staff too. A tug-of-war between Internet users and the bricks-and-mortar crowd has accordingly shifted in favor of the latter.

Out-of-town buyers are the worst hit, having fewer routes to tickets. Bavarians resident outside their capital city — it is the “state” opera after all — and fans of the renowned company as far away as East Asia and North America greatly rely on the Webshop.

The disadvantage is not new at BStO. Indeed the artificial online delays effectively bring to the main season the same narrow price availability for out-of-towners they have long experienced with BStO’s 142-year-old summer Munich Opera Festival. Tickets for the festival are first sold in snowy January in person only, and the lower four of eight price categories — roughly, seats below €100 for major performances — sell out this way when the biggest stars are scheduled, months before online ticketing starts.

Countless customers were surprised by the handicap on Jan. 12, 14, 18, 22, 30 and Feb. 2 while trying to buy tickets for Philipp Stölzl’s new production of Andrea Chénier, due March 12 and starring — gosh — both Harteros and Kaufmann. All performances were affected on those selling mornings, corresponding to BStO’s two-month lead time.

Surprised, and confused actually. The handicap throws up two screens in place of the Webshop. First, a countdown page, labeled with the quaint metaphor “waiting room” to dupe people into thinking the system is too burdened to process their order. This assigns a wait number, which ironically turns out to be far from “stable.” Then comes a standby page, for buyers whose number has dropped to 0 (zero) before the Webshop opens, i.e. before 10 a.m. — a strange situation, one might think, but the only one with potential to yield broad ticket choice.

Not-so-hypothetical scenarios:

Unaware of the handicap, she logs on at 9:55 a.m. She faces not her expected Webshop but the countdown page. (She would be there regardless of what event and date she is pursuing. The whole operation is impacted that morning because one heavy-demand performance is going on sale.)

She has of course no idea when the handicap was activated. (The answer could be 6 a.m., about when a physical line might start outside the Tageskasse.) But she is less troubled than buyers who may have purposefully stopped work in Tokyo or climbed out of bed in Boston.

She sees 29 lines of precise instructions auf Deutsch, unless she has opted for English screens, in which case she sees a remarkably compressed version of just five lines. (The complete English is here.) Key instruction: “Do not refresh.” Below, she reads her wait number: a high one, 400. Her chances are nil, but she doesn’t know this. She ties herself up for an hour before learning.

Logs on at 5:55 a.m. She is too early and goes straight into the normally functioning Webshop. She assumes she can just wait there until 10 a.m. But no. She must refresh the screen every twelve minutes or be disabled for inactivity. No instructions say this because the system was in normal mode when she entered. (To see them, she would have had to arrive via the countdown page and witness her wait number drop to 0 before 10 a.m.)

When she casually returns to the screen at 9:30 a.m., she discovers the Webshop inactive for her. She reloads. Now she is on the countdown page with number 200. Again no chance.

Fares better. He logs on at 6:15 a.m., apparently just after the handicap was activated. He lands on the countdown page with number 10. Like A, he is told not to refresh. He obeys. Later, but before 10 a.m., his number drops to 9, then 7. He wonders how this could be. No orders are being processed. (Possible answer: people on the standby page are failing to refresh and losing their place.)

But for him to succeed, his number must drop to 0 by 10 a.m. Otherwise, whether he’s at 400 or 4, he will be stuck on the countdown page during the crucial initial selling minutes.

Luckily he does drop to 0. He is moved to the standby page, a promising but precarious place. There he sees the instruction to refresh that N missed. He must do this every twelve minutes until 10 a.m. If he has arrived on the standby page early, say at 7:15 a.m., he will be doing a lot of refreshing. Should he fail — just once — he will find himself back on the countdown page holding a high number. (Anja and Jonas never wanted it that way.)

When the hour rolls around and the handicap ends, he must be ready, as in the past, to point and click with decisiveness and accuracy. His seats are secure only when they appear in his Einkaufswagen, the shopping cart.

A, N, and R may be imagined. The following numbers are real, recorded during the Jan. 18 handicap on Andrea Chénier ticketing in checks using two browsers and two connections:

Logging on at 10:24 a.m., a wait number of 688 with 170 seats left to sell. Three minutes later, wait number 346 with 130 seat left. At 10:43 a.m., number 179 with 38 seats. At 10:54 a.m., number 40 with 19 seats. After another five minutes, access to the Webshop with 4 seats shown as available. By 11:04 a.m., 2 seats left but neither one of them moveable into the shopping cart. At 11:07 a.m., sold out, Ausverkauft. Despite this, a new buyer could log on at 11:10 a.m. and receive wait number 382, which would drop to 0 six minutes later and lead to an empty Webshop.

Bavarian State Opera should end this nonsense. The company is damaging its reputation and working against its own carefully evolved ticket structure and sales procedures, designed to draw people of all income levels from a broad geography.

Those procedures sell tickets three ways: subscription; single-event by written order; and single-event by immediate fulfillment. The latter two are processed on a staggered basis according to performance date. Written orders (traditional mail, fax, email) are worked three months out. Immediate-fulfillment sales (online, phone, physical presence in the Tageskasse) begin two months out.

Each single-event method draws on fixed set-asides, or Kontingente, of seats in the 2,100-seat National Theater. These are broken down across BStO’s eight price categories and to within specific seating blocks, to as few as two seats, allowing near-total price and seat choice for each method. Quite sophisticated. And really quite fair, at least in the case of written orders. Even without handicapping, though, buyers outside Munich have less access to the immediate-fulfillment set-asides: getting to the Tageskasse may not be possible, and phoning is hard when there is heavy demand. Naturally they depend on the Webshop — and their hot connections, firm wrists, pinched fingertips and nanosecond nerves.

CTS Eventim, far from warranting criticism, could be held up as a most capable and user-friendly ticketer. Certainly its system offers an easier buyer interface, more precise seat sectioning, and lower fees, than that of the larcenous near-monopoly Stateside.

Instead of blaming its vendor, the opera company needs to go back to the future and solve its delicate Tageskasse problem with rigor and honesty. This means two things: adjustments to the Kontingente to reasonably protect in-person buyers; and an announcement of the change. Any tactic resulting in Internet screens that mislead buyers and waste their time, or too weird to spell out in a news release, is a bad one.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Staatsoper Imposes Queue-it

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Antonini Works Alcina’s Magic

Portraits For a Theater

Staatsoper Objects to Report

Tags:Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Commentary, CTS Eventim, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, News

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Concert Price Check

Saturday, September 3rd, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 3, 2016

MUNICH — Visiting orchestras cost more for concertgoers. But why exactly? Several factors govern ticket prices on tours, often mitigating each other, and all have a bearing this month as three orchestras from this city hit the road:

— Bavarian State Orchestra (BStO) with Kirill Petrenko, general music director

— Munich Philharmonic (MPhil) with Valery Gergiev, chief conductor

— Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO) with Daniel Harding, guest conductor

Here at home these orchestras cost as follows, sampling the top prices for a regular concert without subscriber discount: BStO in the National Theater, U.S. $78; MPhil in the Gasteig, $68; BRSO in the Herkulessaal, $73. Tickets in all price categories include bus and train fares to and from the venue within a 25-mile radius.

Government subsidy, at the federal, state, and in the MPhil’s case city levels, holds down prices to ensure that all Munich audiences can afford to attend. It does not necessarily vanish on tour, at least not within Europe.

For instance, at Berlin’s Musikfest this month, a six-hour drive from here, you would pay a reasonable and consistent top price of $100 for the visiting BStO, MPhil or BRSO, with subsidy applying both to the festival and, federally, to the three German orchestras.

Lack of subsidy may seem to explain exorbitant prices at Lucerne’s Sommer-Festival in Switzerland. Or is a profit motive kicking in? Actually a third factor causes them: currency exchange and the robust Swiss franc. Lucerne, just four hours by road from Munich, wants $245 and $296 for the BStO and MPhil, respectively.

That last detail raises the issue of perceived worth. Why would Lucerne charge a premium for one Munich orchestra over another when Berlin prices all three equally? For that matter, why does Berlin ask more for visiting orchestras than for its own Konzerthaus-Orchester (at a $69 top, staying with the “regular concert without subscriber discount” benchmark) or Berlin Philharmonic ($84) when subsidy applies?

The concert presenter directly, and the concertgoer ultimately, places a value on an orchestra in part as a function of geography. In the small Swiss city but not in the German capital, Gergiev’s orchestra (or Gergiev) is valued more highly than Petrenko’s (or Petrenko). In Berlin, people are willing to pay more to hear out-of-town musicians, a flip side to familiarity breeding contempt.

Price-comparing assumes events have been priced to sell out, and sell out at roughly the same pace. Which in turn assumes presenters know their job. They may. But objectively the worth of an orchestra cannot rise or fall by the tour stop.

If beauty is in the ear of the beholder, the Milanese are more attuned than most. So say Teatro alla Scala’s managers by setting a top of $162 for the BStO’s concert there — far below Lucerne prices yet still double the tag at home. Low government funding in Italy helps shape their thinking, rather than any attempt to gouge, though it will make La Scala’s big platea hard to fill.

Otherwise prices vary against a mental cushion: presenters’ realistic belief that ticket buyers will allow for some unknown but fair travel expense being passed along to them, unaware whether such expense has been covered by grants. Traveling more widely than the other orchestras this time, the BStO costs $94 in Paris, $107 in Vienna and $117 in Luxembourg.

Back in Germany on dates in between those stops, the limited revenue potential of relatively small halls may explain BStO top prices in the range of $118 to $144 for Bonn, Dortmund and Frankfurt. Either that, or someone is profiting, an alien notion when the very existence of orchestras requires subsidy.

Presenters of visiting orchestras are indeed on occasion out to make money, just as they do with non-classical artists. NBS in Tokyo has been a world-renowned price-gouger. In Munich the busy presenter MünchenMusik often prices aggressively. There are several more.

What of three Munich orchestras touring at the same time? Music contracts here commonly run “Sept. 1 to Aug. 31,” with the summer months tail-ending the term ostensibly to provide time off. In practice this structure brings chances to earn extra income at festivals instead. September becomes an odd month: the musicians need a break and audiences are sated from summer performances; the main season is supposed to start yet nobody wants to get down to it. So a window opens for touring.

Photo © KKL Luzern Management AG

Related posts:

Concert Hall Design Chosen

A Complete Frau, at Last

Mastersingers’ Depression

Netrebko, Barcellona in Aida

Portraits For a Theater

Tags:Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Berlin, Bonn, Commentary, Daniel Harding, Dortmund, Frankfurt, Gasteig, Herkulessaal, Kirill Petrenko, KKL, Lucerne, Luxembourg, Luzern, Milan, München, MünchenMusik, Münchner Philharmoniker, Munich, Munich Philharmonic, Musikfest Berlin, National Theater, NBS, Paris, Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Teatro alla Scala, Valery Gergiev

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Harteros Warms to Tosca

Sunday, July 17th, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: July 17, 2016

MUNICH — When Anja Harteros was singing her first Toscas three seasons ago, it was clear she had the vocal resources for the role, and the Mediterranean temperament. Even so, the portrayal didn’t quite compute.

Enter Bryn Terfel, a Scarpia to rattle the aloofest, longest-legged of prima donnas. And Jonas Kaufmann, trusted stage buddy, sweet Cavaradossi. Now the diva’s doubt, fear, passion and rage turn on the instant, her slashing knife grip extending a ferrous will.

Harteros fairly lived the part July 1 here at the National Theater, teamed as she must have wanted and apparently undeterred by Luc Bondy’s clunky 2009 stage conception. Warm chest tones and creamy highs, floated or hurled, came into thrilling dramatic focus this time around. Illica and Giacosa’s words made inexorable sense, the Attavanti canvas and Terfel’s guts sure targets.

The tenor, too, had a great night: astutely colored phrases, gleaming top notes, a clarion but unexaggerated Vittoria! For once, E lucevan le stelle emerged as spontaneous thought, always in Kaufmann’s wonderfully lucid Italian.

If the mighty Welshman sounded a smidgen less opulent of voice than in previous Munich Scarpias, his characterization was as potent as ever, and his savoring of Puccini’s lines most enjoyable.

The snag, alas, was Kirill Petrenko’s conducting. Forceful and weighty, it never felt rooted in the language it was supposedly driving. Still, a terrific night for the Munich Opera Festival, and nowhere more refined than during Io de’ sospiri as sung by the Tölzer Knabenchor’s uncredited soloist.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Manon, Let’s Go

Tonhalle Lights Up the Beyond

Busy Week

Time for Schwetzingen

Schultheiß Savors the Dvořák

Tags:Anja Harteros, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bondy, Giacomo Puccini, Kaufmann, Kirill Petrenko, Kritik, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Review, Terfel, Tölzer Knabenchor, Tosca

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Mastersingers’ Depression

Tuesday, May 17th, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: May 17, 2016

MUNICH — Beckmesser blew his brains out at the end of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg last night here in the Nationaltheater. That was after first aiming his gun at the back of the head of Sachs, and after a graphically brutal beating by David and bat-wielding apprentices had left him in a wheelchair — a predicament from which he had miraculously recovered, back onto his feet, within the few hours separating Johannisnacht and Johannisfest. Sachs, for his part, never saw the gun; he was sitting moping because Stolzing had ignored his Verachtet mir die Meister nicht, had declined to honor German art or the masters safeguarding it, and had simply walked out with Pogner’s prized daughter.

Whether Beckmesser’s character is of the suicidal type is a fair, though in context minor, question. Stage director David Bösch’s new production for Bavarian State Opera offers an altogether transformed view of Wagner’s erstwhile comedy, funded by the same hardworking Bavarian people who brought you the first, on June 21, 1868, when Hans von Bülow occupied GMD Kirill Petrenko’s podium.

Swiss-trained Bösch explores the role art can play in society by winding the clock in the opposite direction from the composer. Instead of reaching back three centuries to show the art-guild tradition at its liveliest, when Nuremberg prospered, he forwards us to a faceless town that has seen better days, where the institution feted by Wagner is in yet more jeopardy than when the score was written and where the masters in their trades suffer the effects of debilitating, distant economic forces. Somewhat outside these problems is the presumably flush Stolzing, but even he cannot invigorate through his candidacy a guild whose masters find it easier to delude themselves than honestly confront demise. Sachs’s Wahnmonolog fits right in. Not much else does.

The idea of collective depression finds little use for such musical-dramatic particulars as the scent of the Flieder (lilac) or the shade of the Linde (basswood). Bösch has to invert the humor in, for instance, the Nachtwächter’s round and Sachs’s gift to Beckmesser. He defies Wagner’s time-of-day and lighting directives. Indeed, clashes with the composer create an uneasy mix of narrative, pomp, violence and slapstick (song-trial errors marked via shocks to the applicant in an electric chair; a town-clerk serenade from atop a scissor-lift, constantly raised and lowered by the cobbler).

But Bösch’s own visual-stylistic trademarks are firmly in place, reminding us of his spacy, zoned-out previous work for this company: L’elisir d’amore (2009), Mitridate, rè di Ponto (2011), and, his touching flower-power effort, La favola d’Orfeo (2014). Neatly arranged decay, locally lit props, black limbo backgrounds, a funky insouciance to the stage action: these are some.

The Bavarian State Opera Chorus sang magnificently for this premiere, achieving levels of expressive detail and shading it reserves for its obsessive GMD; Sören Eckhoff did the coaching. Sara Jakubiak from Bay City, MI, made a welcome debut as Eva, acting well and producing girlish tones in mostly clear German. Benjamin Bruns coped sweetly with the boisterous lyric challenges of David. Jonas Kaufmann added the quality of heroic delivery to the youthful ardor and Lied skills evident in his Scottish Stolzing of long ago. Wolfgang Koch, vocally opulent, looked sloppy as Sachs but conveyed enlightenment anyway. He projected his words impeccably and never forced for volume. Markus Eiche’s musically ideal Beckmesser deserved and received the loudest applause, after tough toiling in Bösch’s action. Christof Fischesser intoned nobly and richly through Pogner’s wide vocal range, while the Nachtwächter’s chant seemed all too short as securely phrased by Tareq Nazmi.

Petrenko drew playing of color and sparkle from his Bavarian State Orchestra, favoring momentum (78’ 58’ 70’ 42’) over reflection but pointing the rhythms with ceaseless energy and emphasis, much to the opera’s advantage. Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg will be streamed as video over the Internet at 5 p.m., Munich time, on July 31, 2016, under sponsorship from Linde.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

See-Through Lulu

Time for Schwetzingen

Mélisande as Hotel Clerk

Mariotti North of the Alps

MKO Powers Up

Tags:Bavarian State Opera, Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bayerischer Staatsopernchor, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, Benjamin Bruns, Christof Fischesser, David Bösch, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Kaufmann, Kirill Petrenko, Kritik, Markus Eiche, München, Munich, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Review, Sara Jakubiak, Sören Eckhoff, Tareq Nazmi, Wolfgang Koch

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Guillaume Tells

Wednesday, September 23rd, 2015By ANDREW POWELL

Published: September 23, 2015

MUNICH — Post is under revision.

Still image from video © Bayerische Staatsoper

Related posts:

Nitrates In the Canapés

Muti the Publisher

Honeck Honors Strauss

Kušej Saps Verdi’s Forza

Time for Schwetzingen

Tags:Amanda Forsythe, Andrew Foster-Williams, Antonino Fogliani, Antonio Pappano, Antú Romero Nunes, Bad Wildbad, Bavarian State Opera, Bayerische Staatsoper, Bongiovanni, Bryan Hymel, Camerata Bach Chor Poznań, CD, Commentary, Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Damiano Michieletto, Dan Ettinger, Decca, DVD, Evgeniya Sotnikova, Gerald Finley, Graham Vick, Guillaume Tell, Günther Groissböck, Jochen Schönleber, John Osborn, Juan Diego Flórez, Judith Howarth, Kritik, Luca Tittoto, Malin Byström, Marina Rebeka, Michael Spyres, Michael Volle, Michele Mariotti, München, Münchner Opernfestspiele, Munich, Munich Opera Festival, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Naxos, Nicola Alaimo, Nicolas Courjal, Opus Arte, Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Pesaro, Raffaele Facciolà, Review, Rossini, Rossini Opera Festival, Royal Opera House, Sofia Fomina, Tara Stafford, Virtuosi Brunenses

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Schultheiß Savors the Dvořák

Saturday, December 13th, 2014By ANDREW POWELL

Published: December 13, 2014

MUNICH — Passive accompanist and intent visionary: Gianandrea Noseda managed to be both Nov. 18 in his debut program with the busy Bavarian State Orchestra. For Dvořák’s Violin Concerto (1879) he indulged David Schultheiß in a lyrical reading that generally took its time, ignoring chances in the outer movements to drive rhythms more forcefully. The soloist (and first concertmaster) worked without ostentation. He phrased exquisitely, made the countless dances dance, and clearly relished the supply of melody, presenting the work as a confident if mostly tranquil whole. Fine woodwind contributions brightened the proceedings.

Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony (1907) followed the break at this Akademiekonzert in the orchestra’s ornate crimson home, the National Theater. Now Noseda was in his element, revealing obvious enthusiasm and instinct for the music. Conducting from a pocket-book score, he made these opera musicians sound as if they played Rachmaninoff every week, quashing notions that their mixed schedule prevents adequate rehearsal for concerts. He found ideal balances between the strings and winds, apparently with ease. He allowed partial themes to fall naturally in place, climaxes to build themselves, and unity to emerge through gentle emphasis on material shared between the movements. He injected little dashes of suspense, pounced on and relished each accelerando. But he never overplayed his hand. It was a richly executed performance, urgent in the second movement, duly rapturous in the Adagio, and nowhere identifiable as the interpretation of a non-Russian.

Photo © Wilfried Hösl

Related posts:

Horn Trios in Church

Benjamin and Aimard

Concert Hall Design Chosen

Thielemann’s Rosenkavalier

Kaufmann, Wife Separate

Tags:Bavarian State Orchestra, Bayerisches Staatsorchester, David Schultheiß, Gianandrea Noseda, München, Munich, National Theater, Nationaltheater, Rachmaninoff, Review

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed

Blogs

Archives

Tags

Meta

Musical America Blogs is proudly powered by WordPress

Entries (RSS) and Comments (RSS).