By Rachel Straus

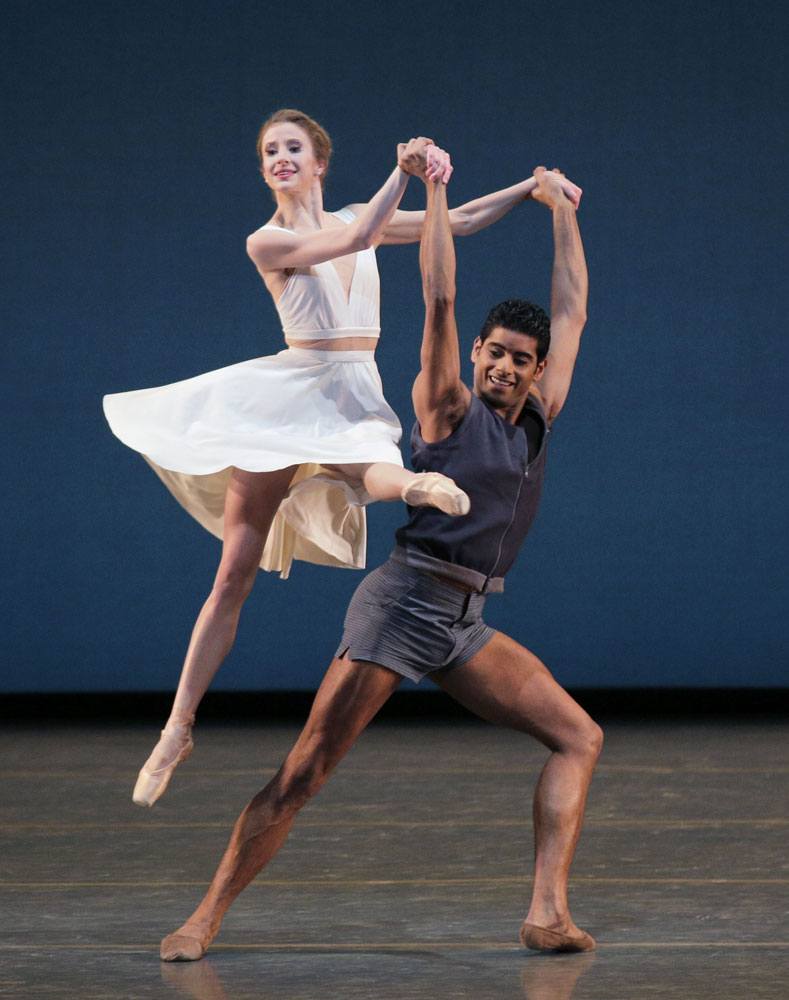

Justin Peck’s ballets are athletic, spirited, musical. The 27-year-old choreographer is pushing the technical envelope of today’s dancers. Far from looking stilted in ballet’s three-century-year old language, Peck’s dancers appear unleashed by, and often euphoric in, his ballet-rooted aesthetic. Yet despite Peck’s adherence to tradition, he is nothing but a contemporary choreographer. His combination of steps are so complex that 20 years ago the dancers might not have been able to realize them.

Peck, who has been dancing with New York City Ballet since 2007, was named resident choreographer of the company in 2014. His third first piece for City Ballet was Paz de la Jolla, inspired by and is set to Bohuslav Martinů’s Sinfonietta la Jolla. Peck is returning to the music of Martinů for his first commission from Miami City Ballet, a company founded by the former Balanchine principal Edward Villella and now heralded by former Balanchine ballerina Lourdes Lopez. Yet the inspiration for the work, which will premiere at Palm Beach’s Kravis Center on March 27, appears to be less about Martinů’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 1 in D Major (1925) and more about the graffiti art found in Wynwood, Miami. That is, if the promo-video for the new ballet, called Heatscape, is an accurate rendering of the spirit of the work.

In the first moments of Ezra Hurwit and Peck’s Heatscape video, Peck puts on his ear phones, we hear Martinů’s concerto, and we see the tall, boyish choreographer enter Wynwood Walls graffiti park, created by the late real estate mogul Tony Goldman. What follows is the appearance of Miami City Ballet dancers, sailing through the air like dolphins in front of various graffiti murals.

One wonders whether Peck, who is not a Miamian, knows the story behind Wynwood’s recent and massive gentrification, and if he did know it, whether he would choose this place as the backdrop for his promo video.

The story of Wynwood begins in the 2000s. Looking for a place to invest his money, the real estate mogul Goldman took note of the creativity of area’s graffiti muralists. They were illegally using the sides of Wynwood warehouses to showcase their art. Goldman decided to give them legal wall space for their work. And, so, Wynwood Walls were born. More recently, another real estate mogul named David Edelstein began buying up Wynwood’s warehouse neighborhood. Thanks to Edelstein, the working class area has become a hipster mecca. Edelstein’s approach is as follows: buy large swaths of a poor neighborhood, promote urban artists as the symbol of the neighborhood, rapidly gentrify the area into a playground for nightlife and the bourgeois consumption of art, and then kick out old residents. All of this is described in Camila Álvarez and Natalie Edgar’s Right to Wynwood, which won the Best Documentary Short at the 2014 Miami Film Festival.

With this in mind, Peck’s decision to put ballet and Miami graffiti together is problematic. His joining of the two arts occurs not just in his promo video, but also in the soon-to-be-completed stage version of Heatscape. Shepard Fairey, a former graffiti artist, known for his Barack Obama “Hope” poster, is creating the work’s graffiti-esque set design.

Putting ballet and graffiti together is hardly new. The first graffiti ballet was Twyla Tharp’s Deuce Coupe (1973) for The Joffrey Ballet. Back in the 1970s, when Tharp was making Deuce Coupe, graffiti was still considered anti-social. It illegally altered public spaces. By hiring graffiti artists to spray paint the stage backdrop, while Tharp’s ballet-meets-social dance unfolded, she threw into question the notion of high and low art.

Peck, who is a classically trained ballet dancer, rightfully wants to mix the “high” and the “low”; to blend sanctioned and rebellious art forms together. Unfortunately, graffiti is no longer a rebellious art. The establishment has embraced it. In the case of Wynwood, real estate moguls are using graffiti to gentrify the neighborhood. Consequently, Peck’s Heatscape video promo doesn’t express bohemian culture as much as it reveals the corporatization of culture, marketed to young people in spaces owned by real estate titans. Let’s hope Peck’s actual ballet doesn’t fumble so drastically into contested urban spaces, where art and big business are meeting. Let’s hope Heatscape is just a hot dance.