By ANDREW POWELL

Published: December 22, 2013

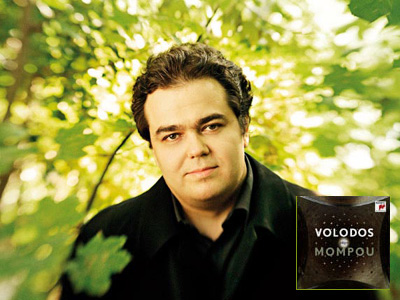

MUNICH — Somewhere between the patent introspection of his new Mompou CD* and the tags of his early Stateside career — “big bravura pianist,” “new Horowitz” — lies an accurate description of Arcadi Volodos. It may simply be this: German Romantic, as in Schumann and Brahms, with impressionist flair.

That was the take, anyway, from a commanding, technically flawless Bell’Arte recital Dec. 12 here at the Prinz-Regenten-Theater, and it is buoyed by the disc. The 41-year-old pianist from St Petersburg stands distant from the trajectory of his rise: 1998 Carnegie Hall debut, Berlin readings of Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky concertos (1999 and 2002). He still plays with strength and vision, but what distinguishes him now is a command of form and the willingness to disturb it in expressive ways.

Stardom, meanwhile, has improbably blurred thanks to the presence of another St Petersburg pianist with what trademark authorities might term a confusingly similar name, Alexei Volodin, 36. (No also-ran, the latter gave a recital himself Dec. 15 at the Mariinsky.) Even so, allegiance to Volodos has held firm, particularly here in Germany, and to its credit his record label Sony Classical has stayed with him.

Schubert’s 1815 C-Major Sonata opened the recital, stitched up with its Allegretto (D279/D346). It seemed a weak choice until Volodos testily hammered and carved his way through, knowing exactly what he wanted from the music. We heard the sound of Beethoven.

The pianist stressed formal commonalities in the standalone pieces of Brahms’s Opus 118 (1893) and allowed contrasts to make their point without emphasis. Full, deep tone colors throughout, and natural lyricism in the framing sections of the A-Major Intermezzo and in the Romance, lent due character. In the final measures of the E-flat-Minor Intermezzo, as poetic cap, Volodos mustered a monumental stillness. (His reported recent success in Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto, with longtime collaborator Riccardo Chailly, is consistent.)

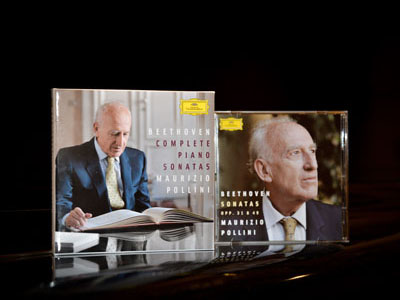

After the break and a fluent Schumann Kinderszenen, Volodos boldly energized the same composer’s C-Major Fantasie (both 1838), its three movements speaking with phenomenal power and passionate unity. For the Finale (Langsam getragen, durchweg leise zu halten), he coaxed a mood of poignant reflection unmatched even by Pollini in the famous 1973 recording (made across town here at the Herkulessaal).

The CD* of miniatures by Federico Mompou (1893–1987), recorded last December in Berlin, is a worthy issue in these times of superfluity. Few distinguished recordings have been made of the Spaniard’s music, and Volodos commits himself intensely to it, judging from his liner essay as well as his playing. Although the output is often related to Satie, Mompou’s late imaginative world (not the style) lies closer to Debussy in his Préludes.

Volodos declares the four Música callada sets (1951, 1962, 1965, 1967) to be peaks of achievement: “ … the music [Mompou] spent all his life moving towards … wrested from eternity, as if it already existed in the Spheres … .” He plays eleven of the pieces, from the total of 28, drawing on all four sets in a sequence his own. This “quietened music” is both abstract and personal, the product of an old solitary man, but not one at death’s door; Mompou lived another twenty years after completing Set 4. Many pieces are “Lento,” a marking that satisfies the composer for divergent exercises in peace (VI), pain and emptiness (XXI), and generalized remoteness or stillness. Others, such as the Moderato XXIV of 1967, flow so plainly and concisely that a marking is hardly needed. The many chilly passages in the Música callada tend to be broken by warm chords in unexpected places.

Volodos revels in the myriad nuances of these valued miniatures and, as in Brahms, downplays contrasts in favor of coherence. He finds fantasy here and there, catches the fleeting moments of excitement, and instantly lets ideas go when they must. The interpretations are light of touch and magical.

Half of the disc holds short independent works, most of them tellingly shaped. In Preludio 12 (1960) and elsewhere, Volodos shows Vlado Perlemuter’s knack for placing just the right weightings in pale adjacent phrases to support a long idea, saving music that could easily sound aimless. The much earlier (1918) Scènes d’enfants suite, home of the cute encore Jeunes filles au jardin, receives an imaginative traversal. Sony’s release is strikingly packaged with photographic details of Antonio Gaudí buildings in Barcelona, the composer’s home town, although typos mar its booklet. The company might now want to entice Volodos into documenting the remaining Música callada.

[*In August 2014 the disc received an Echo Klassik Award.]

Photo © Sony Music Entertainment

Related posts:

Pogorelich Soldiers On

Nazi Document Center Opens

Levit Plays Elmau

Arcanto: One Piece at a Time

Carydis Woos Bamberg

Mozartwoche: January’s Peace

Monday, February 15th, 2016By ANDREW POWELL

Published: February 15, 2016

SALZBURG — There is a pleasure in arriving in Salzburg with snow on the ground. Or maybe the word is reassurance: the city will be real, not a theme park; the people mostly locals, despite the hollowing out of property ownership here; the profile quiet, even intimate, affording a chance to connect with the past. Of Salzburg’s festivals, the snowiest inevitably is Mozartwoche, planned and manned by the Mozarteum to straddle the composer’s birthday, often by more than a week. Last year’s edition achieved a coup by returning horses to the Felsenreitschule, for Davidde penitente as realized by “French equine artist and theatrical genius” Bartabas; next year, managers Marc Minkowski and Matthias Schulz let Bartabas loose on Mozart’s Requiem (Mel Brooks having declined) and promise some thirty concerts besides, including three by the Vienna Philharmonic, with Haydn as “focus composer.”

Mozartwoche 2016, placing Mendelssohn in focus, opened Jan. 22 with spoken words lauding the long contribution of Nikolaus Harnoncourt not only to Mozart’s music but specifically to this festival, where he was again due to conduct before declaring several weeks ago his instant retirement. The packed day teamed Katia et Marielle Labèque with the Mozarteum-Orchester in the morning, continued at 3 p.m. with an András Schiff recital, and ended soberly with Mozart masses at the Großes Festspielhaus led by John Eliot Gardiner. Rewards were many, irritations few.

The matinee sorely needed a conductor to temper dynamics and coordinate the shaping of lines. Where was Ivor Bolton? It began with a Mendelssohn Trumpet Overture (MWV P2, 1826) that knew no piano. Next came Mozart’s E-flat-Major Concerto for Two Pianos (1781) and chronically clunky phrasing by the French sisters; this was redeemed somewhat by a neatly sprung Rondo. Quality rose with a still loud, yet spry, Schauspieldirektor Overture (1786), the music’s inventiveness laid out vividly. The teenage exuberance of Mendelssohn’s Concerto in E Major for Two Pianos (MWV O5, 1823), in conclusion, proved a good match for the Labèques; alas they then imposed a duo encore (and an insipid one, the last of Glass’s Four Movements for Two Pianos, 2008) to ruin our exit.

The Mozarteum’s Conrad-Graf-Flügel and Walter-Hammerflügel (1839 and 1782) stood side by side on the platform for Schiff’s recital. Mendelssohn came first: the Variations sérieuses (1841) and the F-sharp-Minor Sonate écossaise (1833), played on the later instrument with its charming pearly highs and fuzzy, attenuated lows. Schiff made inspired sense of the lines in both works and bound Mendelssohn’s ideas together expertly without shying from a breakneck pace where needed. The Walter’s clarity and evenness through the range made a stark contrast, its modest sound easy to settle into in this artist’s hands. Ideal tempos and immaculate voicing sustained Mozart’s late major-key sonatas, in C (für Anfänger), B-flat and D; the poise of Schiff’s playing overcame passing glitches.

Gardiner’s highly musical, not especially spiritual, reading of the Große Messe K427 (1783) closely resembled the adjusted Aloys Schmitt reconstruction he recorded in London decades ago. His crisp rhythms and airy textures, and the way these flattered the score’s abundant lyricism, seemed designed to please, as if Mozart had composed the truncated service just for today’s Monteverdi Choir and English Baroque Soloists. From this listener’s seat, vocal soloists Amanda Forsythe, Hannah Morrison (sopranos), Gareth Treseder (tenor) and Alex Ashworth (bass) could not be seen or properly heard, but the choir, also mostly out of view, sounded disciplined. Orchestrally it was a performance with resilience, wary balances, individual style; veteran sackbuttist Stephen Saunders managed to nod off during Forsythe’s Et incarnatus est, nearly losing his instrument off the riser’s edge. A horseless Mozart Requiem followed the break; for practical reasons we could not stay.

Photo © Tourismus Salzburg

Related posts:

Salzburg Coda

Horses for Mozartwoche

Mariotti North of the Alps

A Stirring Evening (and Music)

Maestro, 62, Outruns Players

Tags:András Schiff, Bartabas, Commentary, English Baroque Soloists, Felsenreitschule, Großes Festspielhaus, John Eliot Gardiner, Katia et Marielle Labèque, Mendelssohn, Monteverdi Choir, Mozarteum, Mozarteumorchester, Mozartwoche, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Piano, Review, Salzburg, Sonate écossaise, Variations sérieuses, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed