By Rebecca Schmid

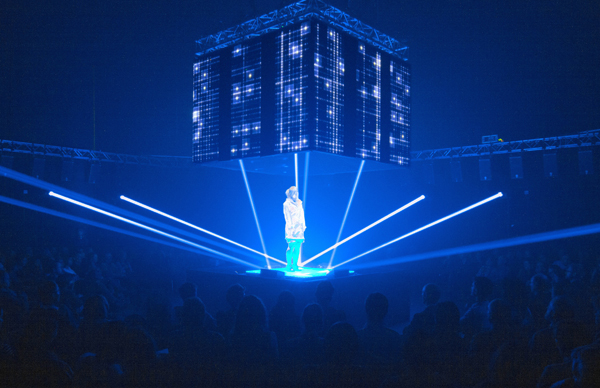

In an age of pervasive digital technology and avatars, it was only a matter of time before virtual experience infiltrated the concert hall. No handmade reeds, no tailcoats. Instead, over 70 synthesized speakers encircling the audience. The Berlin-based ensemble phase7, for a new production of Morton Feldman’s opera Neither, has replaced the live orchestra with 3D surround sound created through the spatial audio production procedure of wave field synthesis. The soprano Eir Inderhaug, trapped in a cage of light beams, provides the only human presence. The production premiered at the Festspielhaus Hellerau in Dresden last March before coming to the Radialsystem this month as part of the festival “The Art of Listening,” which included a conference chaired by the University of Potsdam.

A panel discussion following the concert, seen June 13, concluded that new formats were instrumental in preserving the classical tradition as it struggles to assert its value in today’s society, emphasizing that individuals’ different ways of listening must be addressed both in education and in the concert hall. The Radialsystem, founded in 2006 as a creative arts space, champions experimental modes of presentation such as late-night listening in which audience members can stretch out on yoga mats and musical wine tasting. As a positive sign for the future—even for those who prefer certain formalities of the concert hall—the Kreuzberg venue also attracts listeners who do not constitute a regular following for Berlin’s mainstream classical institutions.

A casually-dressed crowd filled the small back space of the Radialsystem’s main concert hall for Neither, given a clubby atmosphere with the help of smoke machines. Whirring surround sound amplified the static, high-pitched tones of Feldman’s opening bars as the first beams of light broke through the darkness. Inderhaug, a very pregnant figure dressed in all white, crouched silently on her platform at the center of the room. Yet the screeching faded mysteriously after about five minutes. A woman in a backpack emerged matter-of-factly to inform the audience: “as you know, there is a small technical problem,” as if such occurrences were par for the course. “Where is my conductor when I need him?” Inderhaug joked to the audience.

The experience was slightly demystified as the opera recommenced a few minutes later, this time traveling through churning industrial sounds and what sounded like a giant percussion set before yielding to the soprano’s existentially unresolved opening line, “to and fro in shadow from inner to outer shadow.” Neither, true to its name, is a negation of operatic convention and emerged after Feldman and Samuel Beckett discovered a mutual distaste for the genre upon meeting at Berlin’s Schiller Theater in 1976. Shortly thereafter, Feldman received a postcard with an 87-word verse that would provide the libretto for his monodrama, which premiered at Rome Opera the following year. Feldman’s economic, or minimalist, use of material—unsettling atmospheric drones, spiraling melodic figures, cavernous echoes—found an outlet in Beckett’s terse yet open-ended poetry.

The experience was slightly demystified as the opera recommenced a few minutes later, this time traveling through churning industrial sounds and what sounded like a giant percussion set before yielding to the soprano’s existentially unresolved opening line, “to and fro in shadow from inner to outer shadow.” Neither, true to its name, is a negation of operatic convention and emerged after Feldman and Samuel Beckett discovered a mutual distaste for the genre upon meeting at Berlin’s Schiller Theater in 1976. Shortly thereafter, Feldman received a postcard with an 87-word verse that would provide the libretto for his monodrama, which premiered at Rome Opera the following year. Feldman’s economic, or minimalist, use of material—unsettling atmospheric drones, spiraling melodic figures, cavernous echoes—found an outlet in Beckett’s terse yet open-ended poetry.As an “anti-opera,” the approximately 50-minute work lends itself well to phase7’s forward-looking concept, and yet the digitally-generated orchestra rarely proved its advantages over the more visceral experience of hearing live music. The metallic timbre of Feldman’s swelling chords, while often larger than life with this technology, took on a slightly digital quality that disengage the music’s emotional core, even as the sounds ricochet strategically from one speaker to the next. Visually, the isolation of the soprano, who hovers through an internal passage to an “unspeakable home,” is an effective dramaturgical solution to a work that does not lend itself easily to stage direction, yet holographic projections surrounding Inderhaug at times dehumanized the experience. On one occasion her stratospheric, incomprehensible tones made me think of the alien opera singer in The Fifth Element (vocal writing lies consistently above the treble clef, making it difficult to pronounce consonants, although a 1997 recording with Sarah Leonard and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra at least makes it clear throughout that she is singing in English).

It is a paradox that such events are touted as an innovative means of reviving classical music when orchestras throughout the western world are fighting to prove their raison d’être, and in some cases struggling to survive. As it happens, the same orchestral technology employed by phase7 was just on display at the Sydney Opera House for a production of Korngold’s Die Tote Stadt. That classical formats must evolve along with certain contemporary social trends is without question—video projections, DJ shows, and some degree of genre-bending will likely become standard fare for orchestras in future decades—but digital technology is no replacement for a gathering of trained musicians who rely on their brains rather than a circuit board. It is of course counterproductive to fight a certain amount of inevitability: the iPod and internet aesthetics may have already influenced the way we experience all kinds of music. 3D surround sound could provide a myriad possibility of tools to composers and be combined with live orchestra to powerful effect, but as Leonard Bernstein once said, music is about “flesh and blood.”

A l’Arme!

Despite Berlin’s growing reputation as the European mecca of the avant-garde, a platform for contemporary jazz was nowhere to be found until A l’Arme!, or Alarm (July 18-21) debuted at the Radialsystem this week. Bringing together artists from the U.S., Asia and across Europe, the program boasts artists such as the singer Neneh Cherry, returning from a 16-year hiatus in a new collaboration with the Scandinavian quartet The Thing, and German saxophonist Peter Brötzmann, something of a jazz icon on the continent. “There’s no better place than Berlin to burst open the cocoon of an entire scene whose self-absorbance is misunderstood as innovative,” state the program notes in a somewhat awkward translation. Indeed, it is no easy task to define free jazz. The movement emerged in the 1960s as a reaction to predetermined tonal structures, regulated timbres, and rhythmic conventions, eventually digging roots in Europe when the genre proved itself commercially untenable in the U.S.. Starting in the 70s, the term ‘avant-garde’ emerged as an alternative to describe this restless yet organized music, pioneered by figures such as John Coltrane, Sun Ra, and Ornette Coleman.

As evidenced by Alarm’s opening concert on July 18, a fine line often lies between what we call ‘new’ music in the classical realm and contemporary jazz. A trio formed by festival founder and pianist Louis Rastig with American clarinetist/saxophonist Ken Vandermark and Korean cellist Okkyung Lee opened with serialist patterns that were met with wild, meandering melodies and sawing, scampering motives. The musicians’ disparate improvisations managed to create a satisfying whole as frenetic, insistent patterns interwove with electric energy. A quieter middle section featured a repeated two-note figure in the piano, eventually picked up by a bass saxophone before Vandermark moved into squeaking slides and mechanical whirring. Rastig anchored the group with a charged physical awareness and strategic spontaneity, hitting across the keyboard with flat hands in child-like rebellion on more than one occasion, while Lee contributed a rumbling, shivering interlude that was sensitively echoed by Vandermark.

New York-based trumpeter Peter Evans opened the program with free improvisation demonstrating a virtuosic range of contemporary technique and multi-phonics. Muted trilling, wispy reverberations, exasperated blaring, raspberry blows—there is nothing Evans can’t create with his mouth and the valves of this instrument. The most impressive was his performance with a piccolo trumpet in which he broke out into traditional jazz melodies before reverting suddenly to gasping and sucking noises, creating an ironic halo of nostalgia around the sanguine 1950s style. His last act involved the simultaneous playing of a normal-sized trumpet against the piccolo, fluttering the valves of one instrument against the siren-like blare of the other. When Evans pushes through the call of the trumpet in full force, it is as if the instrument’s internal force has been stirring anxiously behind decades of experimentation.

The main hall of the Radialsystem spilled over with fans for The Cherry Thing, as one-time blockbuster Neneh Cherry dubbed her appearance the with The Thing in reference to their album which was released last month. The ensemble’s jazz-rock idiom is not an obvious match for Cherry’s smooth, hip-hop grooves, but she proved herself fearless enough to give a raspy (and slightly inaudible) scream over the cacophony of Mats Gustafsson’s indomitable saxophone, Paal Nilssen-Love’s across-the-board drums and the electric guitar of Ingebrigt Haker-Flaten in the opening number. The following song “Dream baby dream,” with its cooing vocals over saxophone and double bass in a unison melody that yielded to tonal counterpoint over soft drumming, proved a more effective blend. The Thing’s angry riffs lent themselves well to “Cashback:” you eat me for breakfast when you feed me… you spend me like money, sang Cherry over a catchy beat, her curls bouncing freely as she moved around stage in a black dress and sneakers. Ultimately it was unfortunate to experience this music in a seated hall; such danceable fare lends itself better to a small club, where listeners can chat quietly or sway with the music, and more vehement rock passages were too loud for the space. Still, it is exciting to have more intellectually challenging avant-garde fare combined with music of more popular appeal under one roof. A l’Arme has filled a niche that is likely to grow as jazz musicians of all breeds experiment with new outlets of expression.

The main hall of the Radialsystem spilled over with fans for The Cherry Thing, as one-time blockbuster Neneh Cherry dubbed her appearance the with The Thing in reference to their album which was released last month. The ensemble’s jazz-rock idiom is not an obvious match for Cherry’s smooth, hip-hop grooves, but she proved herself fearless enough to give a raspy (and slightly inaudible) scream over the cacophony of Mats Gustafsson’s indomitable saxophone, Paal Nilssen-Love’s across-the-board drums and the electric guitar of Ingebrigt Haker-Flaten in the opening number. The following song “Dream baby dream,” with its cooing vocals over saxophone and double bass in a unison melody that yielded to tonal counterpoint over soft drumming, proved a more effective blend. The Thing’s angry riffs lent themselves well to “Cashback:” you eat me for breakfast when you feed me… you spend me like money, sang Cherry over a catchy beat, her curls bouncing freely as she moved around stage in a black dress and sneakers. Ultimately it was unfortunate to experience this music in a seated hall; such danceable fare lends itself better to a small club, where listeners can chat quietly or sway with the music, and more vehement rock passages were too loud for the space. Still, it is exciting to have more intellectually challenging avant-garde fare combined with music of more popular appeal under one roof. A l’Arme has filled a niche that is likely to grow as jazz musicians of all breeds experiment with new outlets of expression.

Muti Taps the Liturgy

Tuesday, January 8th, 2013By ANDREW POWELL

Published: January 8, 2013

RAVENNA — Sacred music has lent gravitas to Riccardo Muti’s career since the 1960s. Settings of the Ordinary and the burial service by Bach, Mozart, Cherubini, Schubert, Berlioz, Brahms and Verdi have drawn his attention and received, more often than not, a disciplined performance.

No, this is not the repertory that leaps to mind when discussing the maestro from Molfetta. The operas of Verdi come first, and peer names like Arturo Toscanini, Herbert von Karajan and Claudio Abbado are soon raised. Muti the Verdian enjoys high standing — so high that he will be valued long after his own burial service for a trove of Verdi readings wider than Abbado’s, more eloquent than Karajan’s and better sung than Toscanini’s. (In context, it is worth hoping that his new biography of the composer will offer greater insight than his patchy 2010 autobiography.)

But music for the church points to the heart of this artist more directly than any opera. Where Abbado sees himself as a gardener, Muti’s alter ego is equipped as historian. Muti studies and diligently performs Mass settings — and antiphons, canticles, hymns and oratorios — out of a perceptive sense of their place in history, in a composer’s output, in the genesis of compositional technique and thought.

The effort is somewhat thankless. Sacred scores, particularly whole services, lack sway in a secular society and often lack musical balance too because of the characteristics of the liturgical sections. Many are front-loaded by a euphoric Gloria. Most end soberly, Haydn’s Paukenmesse being an exception to prove the rule. An established conductor who is not a choral conductor needs no Mass setting to boost his reputation, impress authenticists, sell tickets or oblige a record company. Yet Muti has forged ahead, Pimen-like, documenting scores others have not deigned to read. In one championing example, he has chronicled in sound no fewer than seven services by Cherubini.

In 2012–13 three sacred-music projects occupy him. Last August with the Vienna Philharmonic he persuasively reasserted his advocacy of Berlioz’s flamboyant, long-mislaid Messe solennelle, which he sees as a tribute to Cherubini, and this April in Chicago he revisits Bach’s B-Minor Mass.

Three weeks ago in Munich came Schubert’s A-Flat service, a non-commission from 1822 (D678). The songsmith struggled with its form. He did not follow early polyphonic precedent in imposing thematic unity; did not enjoy Bach’s or Haydn’s flair for satisfying church provisos while enhancing structure; did not write his own rules as would Berlioz and Verdi. Five handsome musico-liturgical sections were the result. A serene Kyrie and a radiant Agnus Dei, each with inventive, contrasting subsections. A protracted and prodigious, finally portentous, Gloria. A Credo that covers its narrative ground with storyteller fluency. A pastel-pretty Sanctus sequence. Call them Mass movements in search of containment.

Undeterred by the implicit challenge, Muti for his Dec. 20 concert with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra chose an 1826 revision that caps the Gloria with a bulky fugue, for Cum Sancto Spiritu. He made no attempt to harness Schubert’s ideas: sectional detachment and stylistic incongruities spoke for themselves, often elegantly.

Vocal and instrumental forces cooperated under tight reign, temporal more than dynamic. The BR Chor sang with customary refinement, applying Teutonic conventions in the Latin text. Ruth Ziesak and Michele Pertusi reprised the parts they took when Muti led this music in Milan’s Basilica di San Marco ten years ago. Still fresh of voice and keen to give notes their full value, the soprano found her form promptly after a grainy opening to the Christe eleison. Pertusi, in the modest bass part, blended neatly with his colleagues. Alisa Kolosova contributed an opulent alto, Saimir Pirgu an articulate, secure tenor; he participates in all three of the conductor’s Mass projects in 2012–13. On the Herkulessaal program’s first half, Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony received a mundane traversal except in its agitated fourth movement, where taut rhythms left a lingering impression. The orchestra played attentively in both works.

Tepid applause followed the Mass, a contrast to the cheers that had erupted in Salzburg after the Berlioz work. Was this foreseen? Disappointing? In Italy they say Muti is addicted to applause. More likely is that audience reaction is beside the point for him: he simply wants clean execution, and he received it in Munich. Muti: “ … non siamo degli intrattenitori. La nostra professione è di un impegno maggiore … .” Pimen turns another page.

Toscanini and Karajan, those fellow Verdians, are not remembered for works destined to fall flat in concert. Both built careers on small sacred repertories: some half-dozen Mass settings each, beyond the not-quite-liturgical requiems of Brahms and Verdi. Beethoven’s hyper-developed and intimidating Missa solemnis had pride of place. Karajan revered the Bach as well (29 performances) and occasionally turned to Mozart’s Great C-Minor Mass and Requiem.

Abbado has, like Muti, taken up two Mass settings by Schubert: the tuneful early G-Major, which Muti performed in Milan twelve years ago, and the resourceful, variegated E-Flat Mass, the composer’s last. This work he paired with Mozart’s Waisenhausmesse (1768) in a jolly two-service concert in Salzburg six months ago. Both conductors have performed the two mature Mozart works and the Brahms and Verdi, but curiously neither man has tried a Mass setting by Haydn or Beethoven, casual research suggests.

To be sure, sacred music is not the mainstay of Muti’s career. His commitments to the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, to the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and to Italy’s young-professional Orchestra Cherubini pull the emphasis elsewhere. But the passion for historical context that drives his Mass projects also shapes his priorities in symphonic repertory and opera. Instilled surely during formative years in Naples, it accounts for starkly independent programming choices and probably explains his famously firm way with the details of a score: the chronicler demands accuracy as well as loyalty to the composer. A tempo, però!

By happenstance this post is being drafted a few yards from the home of Muti and the tomb of Dante. They lie in opposite directions.

Photo © Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Paesaggistici

Related posts:

Spirit of Repušić

Muti Crowns Charles X

Muti the Publisher

Netrebko, Barcellona in Aida

Safety First at Bayreuth

Tags:Alisa Kolosova, Arturo Toscanini, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, BR Chor, Cherubini, Claudio Abbado, Commentary, Giuseppe Verdi, Herbert von Karajan, Michele Pertusi, München, Munich, Orchestra Cherubini, Ravenna, Recensione, Review, Riccardo Muti, Rome Opera, Ruth Ziesak, Saimir Pirgu, Schubert, Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks

Posted in Munich Times | Comments Closed