By Rachel Straus

While the New York Times paints Spain as a country on the verge of collapse, the view from the streets of Madrid and Salamanca is quite different.

Yes, the restaurants are not as full, but that cannot be said of the bars. At Madrid’s Plaza de Toros de Las Ventas on May 27, the stadium was packed. Though the bullfights are a far cry from ballet or experimental dance, the posture of the toreadors (bullfighters) are inescapably similar to the stance of flamenco dancers: the arch of the back, the puff of the torso, the legs pressed together. The men even rise to relevé (the tips of their toes) before running toward the bull with flags that end in sharp knives. The overall experience is a bloody one. But unless you’re a vegetarian, you can’t escape being complicit in violence toward animals. Humans kill them for sustenance. Cows and chickens generally live lives of abject misery, and the process by which they come to urban tables is hidden. With the bullfight, the ritual reenactment of slaughter is raised to the level of art. The enormous animals are given names, have carefuly recorded family trees, and when they are about five years old, they fight for their lives to the accompaniment of live music. In rare cases, when one bull outsmarts a dozen gorgeously costumed men, in 15 to 20 minutes of fighting, the president of Las Ventas grants the animal its freedom. This winner returns to the countryside to grow old in privileged circumstances.

Compared to Madrid’s tickets prices for the bullfights (30 to 80 Euros), Salamanca’s Obra Social de Caja hosts performances and lectures about Spanish culture for practically nothing (3 Euros). Salamanca, an ancient city northwest of Madid that boasts the nation’s oldest university, isn’t known for its flamenco. But on May 24, the singer Sebastián Heredia Santiago performed for more than an hour at el Teatro de la Caja. Accompanied by guitarist Juan Antonio Muñoz, Santiago, known as the Cancanilla (the trickster) of Málaga, carried on an impromptu conversation with his fans in the audience. “Eres simpatico” (you are nice), shouted one lady. Cancanilla returned the compliment and thus began the love-in. Cancanilla, who has performed in the companies of José Greco and Lola Flores, and who looks like an amiable bullfrog because of the width of his throat, possesses a booming, plaintive voice that needs no amplification. He teased the audience, saying that he was going to get up and dance flamenco. I doubted the veracity of his statement, but Cancanilla kept his promise. What was astonishing was that this trickster can approximate the same nuanced power with his legs as he can with his lungs.

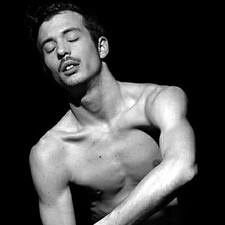

Unlike in the United States, Germany, and France, modern dance never flourished in Spain. That, however, does not mean that it doesn’t exist. On May 25, at Madrid’s El Huerto Espacio Escénico, modern dancer and choreographer Manuel Badás presented his one-man show Sebastián. The French-trained artist skillfully connects Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom with gay culture’s punishment of the body in its quest for physical perfection. Though it was not touched upon, gay men began pumping iron and obsessing about their abdominal muscles in increasing numbers with the AIDS crisis. Looking physically invulnerable, and sexy, was the community’s defense in the face of so many deaths.

In Sebastián, Badás creates a montage of stereotypical homosexual images: the drag queen with his five-inch heels, the cover model in white underwear, and the regular guy pouring over glossy male magazines, whose pages are riddled with advertisements for beauty pills and creams. Again and again, Badás transformed back into the martyr Sebastian. His stomach contracted as though struck by an arrow. His arms fluttered behind his back, like he was manacled and he was sprouting wings. He swirled across the floor, as though transcending rough terrain. Throughout, the music ricocheted between the past and present: from baroque hymns to classic American rock and jazz. Biblical quotes about Sebastian’s martyrdom were projected and Badás’ dancing became increasingly kinetic. In the last section, a recording of Billy Holiday singing Strange Fruit was heard. The young, lithe Badás lined up his glossy magazines in the shape of a cross. He tilted his body over a chair, becoming a strangely suspended fruit, one that has been martyred by today’s media-saturated forces.

George Bizet’s Carmen is a well-worn score. Flamenco companies, opera troupes, and car commercials have taken a bite out of the 1875 composition by the French (not Spanish) composer. On May 26 at the Teatro Nuevo Apolo, The Ballet Flamenco de Madrid ratcheted up the cliches associated with the Carmen story.

Veronica Santos performed the title role. Choreographer Sara Lezana tipped her hat to Broadway by having her female flamenco dancers bare a lot more leg (and crotch) than is traditionally seen. Carmen is a tale of the gypsy femme fatale, who plays men against each other, has a taste for violence, and whose life ends tragically. She is stabbed to death by her soldier-lover Don Jose (Saulo Sanchez G). Instead of lamenting the vulgar aspects of this production (which could take up several pages), it’s best to mention what was worthwhile. Sanchez danced with elegance and emotional commitment. The decision to interpolate Bizet’s music with live flamenco, performed by a quartet of musicians (including a flutist), helped return Carmen back to Spain, the home of this wonderful art form.